INTERVIEW: Tunde Olaniran on Otherness, Archetypes, and Activism

It can be a daunting thing to challenge stereotypes day in and day out, work for change as a social activist, and rep a town that most of the country writes off as an impoverished wasteland. But Flint, Michigan-based “Afrofuturist” Tunde Olaniran does all of these things as casually as the rest of us might walk to the nearest bodega for rolling papers and a deli sandwich. Born to a Nigerian father and American mother, spending part of his childhood in Germany and London, Olaniran often felt his otherness in acute ways but takes it all in stride while helping the marginalized tell their stories alongside his own.

He’s released two remarkable singles via soundcloud. The first, “Brown Boy” cleverly introduces Olaniran on the most basic terms – that of his skin color – while criticizing the trite narrative tropes that surround race in America. “I’m every single thing you think of me / I’m a sinner, killer, drug dealer, refugee / So keep your jaw locked and I’ll keep the peace / They act like they don’t wanna but man they know me.”

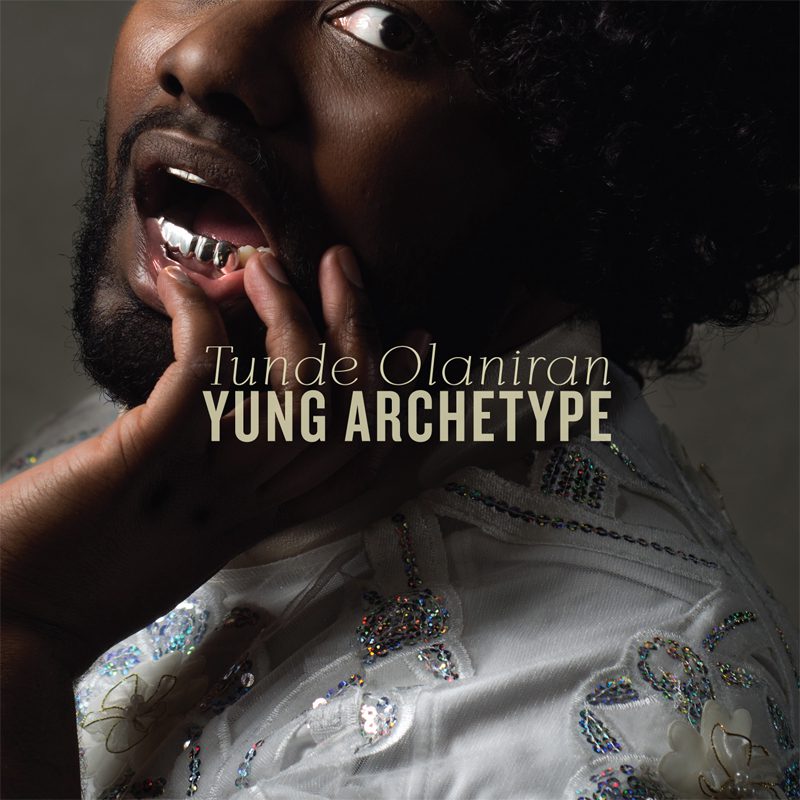

When you get to know Olaniran though, he’s far from a swaggering gangster. He’s driven by sharing the carefree joy he feels when it comes to performing his material, but it’s all propelled by a deeper sense of purpose. Case in point: the beat behind his latest, “The Highway,” hinges on a wonky parrot sample that burrows deep against the ear drum. Once it hooks you, Olaniran lets loose with an intelligent send-up of capitalist progress, gentrification, and cultural appropriation. His messages are never heavy-handed, just extremely astute and delivered with bright, sarcastic jabs packaged in party-ready rhythms. Operating within a genre beset by misogyny, violence, and homophobia, it’s refreshing to be able to simply dance to something you don’t have to compartmentalize to enjoy. Olaniran’s passionate vocals soar between fluid rap verses, underpinned with unique production work that he does (mostly) by himself, encompassing his DIY-gone-glam aesthetic. The single will appear on his forthcoming EP Yung Archetype, out tomorrow (2/25).

We talked with Olaniran over the phone, discussing his many projects as a musician, entertainer, activist, collaborator, and otherwise.

AF: Hi Tunde! Can you describe your sound in a few words for our readers?

TO: My name is Tunde Olaniran, I am originally from Flint, Michigan, where I live now. My sound is kind of that cut-and-paste that you see more and more of now with people having access to so many different sounds. There’s an experimental hip-hop, alternative club/dance feel with some of it. That’s kind of the range of the music.

AF: You’ve described your sound at times as “Afro-futurist.” What does that mean to you?

TO: It’s kind of a mixture of a few things. It bleeds into the performance as well, I think they kind of go hand-in-hand. The sound has influences from the diaspora – my father was a Nigerian immigrant, and my mother was American, so I have a blend of those things. But also, the futurist label is about being really forward thinking and also kind of optimistic in some ways in your capacity to change through the lens of your own identity, not the lens of the dominant cultural kind of thing.

AF: What specifically are you trying to change?

TO: For me, the thing that is most important is people’s ability to express their identities and to elevate alternate narratives. It’s all about the story of someone who is marginalized, for whatever identity – whether they’re a young person, an artist, whether they’re queer, a person of color, whether they’re DIY or funded by the big shiny foundations, whatever. When people say that they’re an ally, being an ally is really about getting out of the way, so that’s what I feel like I work towards in the different aspects of my professional life and my life as an entertainer.

AF: Well in terms of identity, I feel like “Brown Boy” is sort of a fitting intro to what you’re about, in that it’s a critique of stereotypes that surround marginalized cultures. What was your specific motivation behind writing it?

TO: This is gonna sound really ridiculous, but I don’t spend a lot of time coming up with lyrics. I’ve been in writing sessions with people who are, I would say, career songwriters. They live in Nashville, or they’re in L.A. and they write songs for their career. And my approach is so different from that. I don’t usually labor over the lyrics, they kind of just happen as they’re gonna happen. A lot of times, I’m going back and looking at them and saying “What is this? What does this mean or what could it mean?” I don’t wanna make myself out to have this really grand scheme, but I do feel like looking back at the lyrics [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][to “Brown Boy”] after writing them they do feel like a declaration in a way. I think I was singing it more to myself than necessarily trying to establish any kind of stance to external forces or norms or whatever. I think it was like an anthem just for myself living on the margins. And with the video, a lot of people in that video are activists and artists that live in Detroit. After the song was written, I wanted the visuals to really represent that diverse spectrum of people that I’ve gotten a chance to know that I’ve been really influenced by. Those are the people that I hope are gonna be dancing with the song. For me, that’s the most important thing – am I gonna enjoy performing it? Is my good friend gonna wanna dance to it? That’s the focus as much as any other political statement.

AF: So you’re essentially making music that a community of activists can enjoy. Are these people that you’ve come into contact with via your work as an educator? You’re involved with Planned Parenthood, specializing in gender identity, sexual equality, and health awareness.

TO: I actually got introduced to an artist named Invincible who is an MC from Detroit… their work is so intertwined with their political action in social justice movements so just even being at a show with them, I met a lot of really interesting folks in Detroit. I’d been doing social justice work but I feel like those actually were pretty separate. And now I see them converging more. I met someone at a show and it turned out they work at Ruth Ellis, which is a center in Detroit specifically for trans and homeless youth of color. He was like, “Let’s actually do a program, and let’s do some education” and kind of let those meld and for me that feels really good. Planned Parenthood is really good to work for because you can bring your whole self there, so I felt like they were separate but now they’re actually coming together more than they did at the beginning.

AF: Well I think it can be powerful to use artistic expression to forward social movements, and it’s important work. With Yung Archetype, you reference Carl Jung’s theories about universal patterns and images. Which archetypes did you draw on and which are you trying to tear down?

TO: Again, that was another moment where it wasn’t super intentional. The goal wasn’t necessarily to work with one of Jung’s specific twelve archetypes but to really look at the idea of attacking classical or dominant perceptions and imagery. So I took that stance even with the photography and with myself. Starting out as an artist, sending your shit to people, when you’re black on the cover some blogs are like, “We don’t do hip-hop” – even though they haven’t heard the music. But we can’t really send it to rap blogs; clearly it’s not gonna work there, cause I don’t really see myself as a rapper in that way. I’ve always had to deal with those immediate perceptions just walking down the street or being in my body. I’m trying to embrace it but also kind of twist that idea with the imagery for the EP. The lace on the jacket is something that my grandmother sent me, from Nigeria. You get sent traditional lace, yards and yards and yards of stuff and you’re supposed to make a very traditional tunic and pants from it that you wear for ceremonies like weddings, whatever. I was like, well let’s make a Members Only jacket out of it, again taking the classic image of an immigrant’s son or a foreigner and get into touch with both ends of that. I still haven’t shown my grandmother, I don’t know how happy she would be.

AF: I think grandmothers have to sign a contract where they’re just automatically proud of whatever their grandkids make. I think you’re probably safe. I’m sure blending disparate ideas comes in handy when you’re working with other artists. You’ve collaborated with lots of musicians on remixes and various one-offs, including Dale Earnhart Jr. Jr. What goes into those collaborations? How is it different from working on your own material?

TO: I’m really into collaborations so I try to work with people a lot. I have a process for making songs where I produce the track and that really drives my writing and then I write really quickly and I just record it . Even when I had a band we would like write songs in like an hour. Not everyone works that way. Some people do their best work when they have a few days or weeks or whatever to marinate. The best stuff that has happened recently is when I’ve been able to sit down with folks. We live in an age where we do a lot over Dropbox, and you can work across continents, but I really love a chance to sit down. I wrote “The Internet”, a track on the EP, with James Link, who’s sick – he’s really, really amazing. I call him a hipster hermit – he’s really popular, but he doesn’t actually like being around people. I forced him to sit down with me and in ten minutes we had the best fucking hook. It was so great. I just really love being able to be in the same room if possible.

AF: Is there anybody in particular that you want to collaborate with that you haven’t had a chance to yet?

TO: I love Switch, I think Switch is the best. I met him once touring in France with Diplo. Diplo came in, asked us for weed, and we were like we don’t have any left. So then Switch came and sat down and I was super shocked and star struck, so I’m just standing there and we’re in Europe so he was like “Do you guys speak English? What is happening!?” We were just like “Yeah… kind of”. That could’ve been my chance to mess with this dude! But I love his take on pop and the way he mixes and slices things, so that would be the dream collaboration. There’s another band called Jamaican Queens out of Detroit. We’re friends, but we haven’t had a chance to really sit down. We only see each other at shows. I’d love to write with them, because their production is really interesting.

AF: We reviewed “Wellfleet Outro” on AudioFemme! They’re great. Is there anything else in particular that you’re listening to?

TO: Maipei. I saw her at SXSW in 2010, and I was obsessed with her Cocoa Butter Diaries EP. She disappeared for a while, just stopped posting, and then “Don’t Wait” came out and it was amazing. She’s like a Kelis to me, I’m really excited about whatever she’s gonna do after this. The Little Dragons single is really good. I’m into female artists a lot. I’m really waiting for Robyn’s stuff to drop.

AF: Do you wanna talk a little bit about Flint and how it’s shaped your music?

TO: Flint influenced me in that there is a really distinct culture here. Everyone knows everyone else. Word of mouth is kind of the best way to do any kind of communication and marketing. The scene is small and there are two sides of it, like even in Detroit. They’re still very disconnected from the idea of having music as a career, so you’re playing covers or you’re in the hood clubs rapping but the thing I respect is that Flint is just really supportive. I was in a rock band when I was pretty young and in any environment, people are like, into it, you know? There’s never really a demarcation as far as scenes. People aren’t sitting with their arms crossed just looking at you, it’s very very welcoming and open and that gave me some license to try to experiment with what I wanted to do. I knew it would be okay to do that.

AF: Did that feel different from the time you spent in Germany and London as a kid?

TO: In London, I lived with my dad’s family, and they were Nigerian and I didn’t interact with a lot of white British people. I even felt different with them, because I didn’t learn Yoruba like they did. A lot of them had been sent to boarding schools in Nigeria as children, I didn’t have that. Then in Germany I’d have little kids touching my skin ’cause they had never seen a black or brown person. Coming back to Flint, [living with] my mom who was not raised in black culture… when I was young and one of the kids in the neighborhood called me ‘dog’ – like, “yo, dawg”, whatever – I was like “Mom, that kid called me a dog! I dunno what happened!” and she went to the person’s mom saying, “You called my son an animal?” and his mom was like “Are you serious?” So even coming back to Flint, being very out of touch with black culture in the Midwest, just always feeling like that no matter where I am has had an influence on what I do. I think now I’ve finally figured out where I’m most comfortable, but living your life on the margins in one way or another – whether or not you’re oppressed, if it’s still knowing you’re on the margins – has influenced how I go about anything, whether it’s creative or not.

AF: You’ve talked about Flint being an example of the “grief that American ‘progress’ inflicts on poor people and people of color”. What do you feel is the solution to this, if there’s any? Where do you see the future of industrial cities like Flint?

TO: My mom is staunchly Socialist/Communist. I grew up with her kind of in my ear, [saying] only large scale economic change can make a difference, and she has a lot of validity to her views. But I’ve also just gotten to meet, especially in Detroit, people who have been influenced by folks like G.H. Lewes, who writes about emergence theory and the idea that a lot of different actions and activities create a web of change. I think it’s gonna come to a point where we have different small-scale solutions happening, and we reach a stage in technology that is gonna force us to look differently about how we distribute resources. I mean, we can automate and we can advance, but who are the consumers if no one’s working and able to sustain themselves? You’re seeing that happening around this planet right now. Obviously some of it’s really bloody, like in Kiev, but some of it’s really amazing. In Detroit, people are creating their own mesh wireless networks by neighborhood. They’re not using ComCast or Time Warner – they built their own internet network. I think it’s gonna be about people making solutions where they can and where they are the most impassioned, ingrained and connected.

AF: Is that part of what your work with Detroit’s Allied Media Conference is about?

TO: The AMC is the largest North American Convention of independent media makers that meets in Detroit every year. They are really, really focused and it’s cool because it’s very young – I think the average age is around 25. It’s basically a way for independent media makers, especially queer women, people of color, who work in technology and media to share best practices, heal themselves from dealing with fucking oppression all year. You wanna be able to be around people that understand what you’ve been going through, and talk about those instances so you get together to do that. The mesh wireless networks I was talking about came from work at the AMC, for example. I’m one of the track coordinators so we’re trying to look at how sound, in all of its incarnations, can change and affect states, can affect relationships, can change policy. Part of what we’re doing is accepting and soliciting proposals from people to talk about amazing stuff that’s happening all over the country. On the fun side we’re throwing a joint party in DC and New York happening on the same day at the same time. I’ll be in DC with DJ Underdog, Mother Sheister, DJ rAt… We’re gonna have a simulcast where the parties will be broadcast in each space and online to try to raise money to pay for the people that wanna do sessions so they can come to the AMC. That happens April 5th.

AF: That sounds amazing, we’ll have to check out the New York party. As far as your live shows go, they’ve got a reputation for being wild – you bring in dancers, wear elaborate costumes, and the like. Can you explain what goes into putting that together and what the goal is in doing that?

TO: I’m just trying to flail around and be sweaty and not fall over but I wanna enjoy myself and dance! I come from the band mentality where people pay their money, you gotta give ‘em show. So I really just try to incorporate choreography, movement, fun pop, really hard hitting beats. Every show we do someone comes up to me and is like “I love metal, and I’m really into metal but my friend told me come and I actually had a good time” or “I didn’t think I was gonna dance and I ended up dancing” so that’s the point of the show. With the tour dates on the East Coast this spring as well we’re making costumes, and we’ll try to have something a little unexpected in each set. I love playing. In Detroit it got to the point where people are doing the moves. They know the choreography so they’re doing the dances with you. It’s just so fun, to kind of have that momentum.

AF: How do you find time to gear up for the tour and promote the music with everything else you do? Even as much as your activism has come together with music making, you’ve got your hands in tons of projects; you’ve written some sci-fi stories, you’ve done art direction on music videos for other bands… how do you balance all that?

TO: I don’t have a life. Luckily I’m able to make friends with people I’m doing that stuff with! I have good authentic friendships through the work I do but all of my time and energy and money, everything, goes into that work outside of my day job at Planned Parenthood, and even that takes a lot out of me. So I’m tired a lot and I’m trying to take care of myself. It’s tiring, but at the same time, after a show or a really good workshop I just feel really good. I could drop dead tomorrow, so why not just do what I love and have a good time and be a little sleepy?[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]