ONLY NOISE: Wallflower

Self-deprecation is easy. When at a loss for things to write about, I can merely plumb the depths of my humiliating infatuations – never having to dive all that deep (more of a snorkel than a scuba, really). There are so many incriminating things floating atop that black and expansive pool; black, due to its enormity, but also because of its propensity for blackmail.

Yes, I have written about musical guilty pleasures before, but on a more theoretical level. There are always more blood-and-guts specifics to dig into. This mining urge surfaces today, as a bittersweet email drifts into my inbox like a wedding invitation from an ex:

“The Wallflowers – Just Announced”

My organs churn with schoolgirl anticipation. At long last, my decade-old fantasy of singing along to the entirety of “Laughing Out Loud” and the fairly sexist “God Don’t Make Lonely Girls” will become a reality. It will be a belated teen pilgrimage. I shall go alone, wearing white and bearing floral garlands. To prepare for such a momentous occasion, it seems high time I revisit my rapturous and embarrassing affair with The Wallflowers, don’t you think? Me too. (For those of you allergic to the mention of Jakob Dylan’s glittering eyes, stop reading now.)

My initiation to the band’s discography, if I am being honest, was not entirely in order. Like many, I was introduced to The Wallflowers with their 1996 breakout hit, “One Headlight,” the video for which was a big part of my sexual awakening.

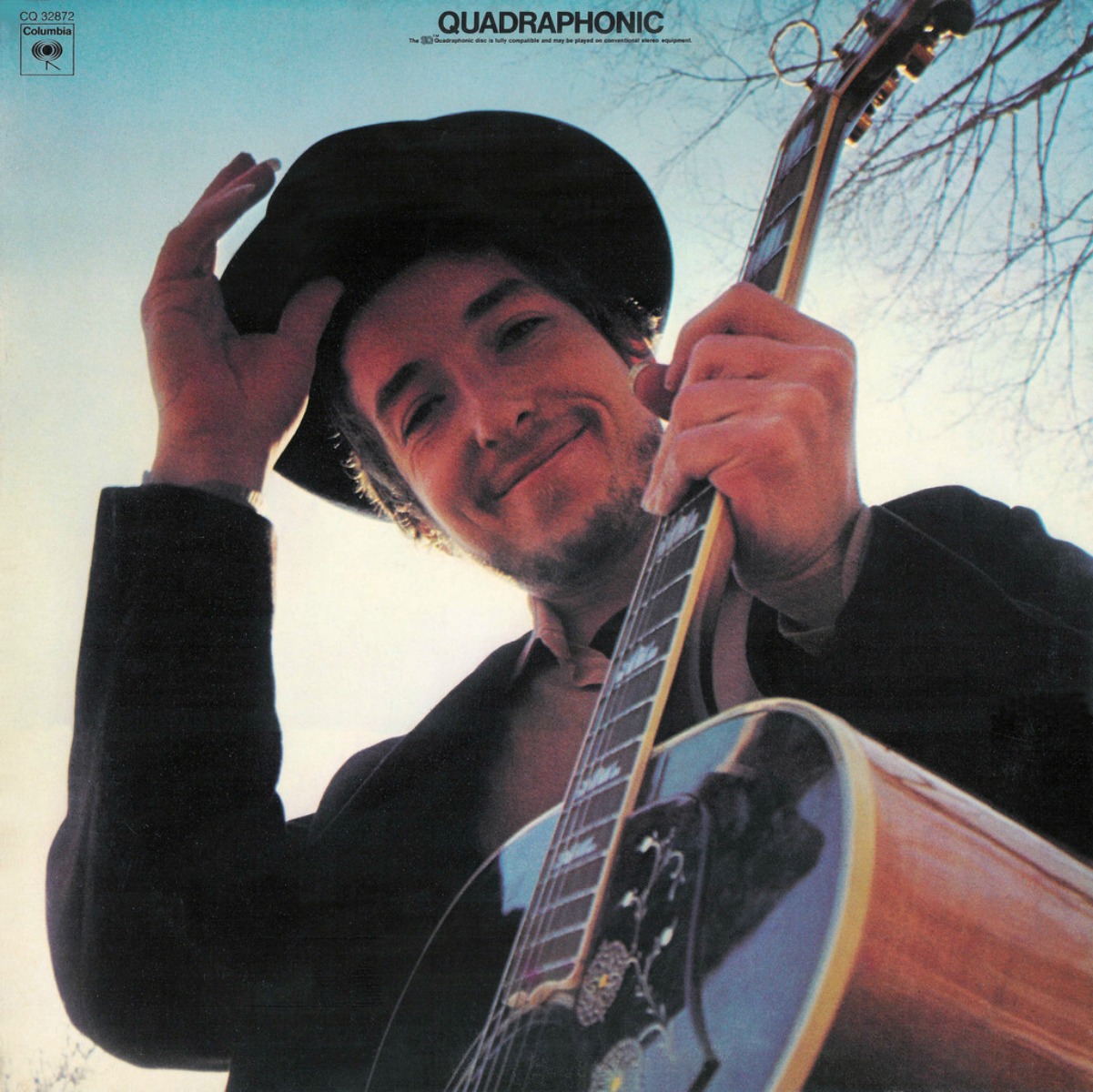

Whether it plagued or graced your TV set, was it possible to deny the beauty of that music video? From a cinematic perspective, it was pretty gorgeous with its deep blacks and sharp highlights…almost as gorgeous as Jakob Dylan’s cerulean eyes, you might say. Dylan’s charisma was undeniable from the start; he was in a meager league of men who could pull off wearing a beaver fedora and sporting a goatee. A man who knew all too well the power of his looks, he spent most of the video sulking around like he didn’t want to be there…and it worked.

My exploration of The Wallflowers in 1996 started and stopped with that song, but it made a lasting impression nonetheless. Somehow the lyrics, “But me and Cinderella/We put it all together” suggested ripe sexual innuendo, causing my older sister to air hump while singing along with them. I naturally followed suit. It was one of the forbidden things we did while our parents were in the other room, like curse and make our Barbies have sex.

Jakob Dylan and his Wallflowers didn’t reenter my life until I was sixteen, and had long since forgotten them. One day, while cleaning out the CD drawer at my mom’s house in 2005, a copy of Bringing Down The Horse appeared in a pile of jewel cases. That black square stared up at me, spangled with goldenrod stars. It was so instantly familiar – I couldn’t remember exactly what it was, but it emitted a fondness…a weighty and warm nostalgia. The thought that I would enjoy this record at that point in my life was pretty improbable – I’d barely welcomed pop music into my ears after five years of a strict punk diet.

And yet, the opening notes of “One Headlight” gave me chills while that Hammond B3 organ flooded my room, enrobing me in ‘90s alt-rock warmth – a description I’m not proud of. Each track seemed better than the last. “Bleeders” bowled me over particularly with its comparable minimalism. Within days I knew the entire record by heart. Within weeks, I had purchased their entire discography, which at that point was five albums deep.

1992’s self-titled, 1996’s Bringing Down The Horse, 2000’s Breach, 2002’s Red Letter Days, and 2005’s Rebel, Sweetheart. I poured through them all, perched on my bed across from my Sony boom box, reading the lyrics along to each track. This was my trusty method for memorizing songs in one sitting. I listened to them each day on the bus, loading up my Discman with a different record Monday through Friday, cycling through their five-CD catalog (in chronological order) during the five day school week.

Of course I had my favorites. The self-titled debut was a little too rough-around-the-edges for me – and not in a punk way. The lyrics were weaker, the song structure less complex, and Dylan’s voice far squeakier. I still love it, but am well aware of its cringe-worthy moments, like “Somebody Else’s Money,” which depicts two lovers stealing their way through life. A loaded topic for the son of Bob Dylan. For me, the artistic pinnacle of The Wallflowers can be found in their third LP, Breach, which was a commercial flop in comparison to Bringing Down The Horse, but was loved by critics (go figure).

The record’s lead single, “Sleepwalker” is a biting critique of Dylan’s own spot in the limelight, depicting him as self-aware of his “pretty boy” status. Where “One Headlight” played into his brooding, glittery-eyed good looks, “Sleepwalker” pokes fun at that posturing.

It’s been a few years since I’ve had a Wallflowers binge session, and I can’t think of a better time to revisit them than now, in preparation for their concert. I’ll start from the beginning. At this café. I will discreetly embarrass myself, praying that no one can hear the sounds of Jakob Dylan’s smoky vocals drifting from my headphones.

Here we go. The commencing snare rhythm from “Shy Of The Moon” off of their first record rattles my memory and I’m squeamishly delighted to hear it. I am smiling and wincing at once, so terrified that the whole coffee shop knows what I am doing. Before the first song is even over, I pull my ear buds out, making double sure that the sweetly bended notes of Dylan’s Telecaster are flooding my ears alone, and not the entire café. I twist the headphone jack, ensuring that it’s securely fitted in my laptop, but still I feel exposed. I am beaming by the time I reach “6th Avenue Heartache” on Brining Down The Horse – beaming far too much for a Tuesday. To my horror, the guy at the next table turns around abruptly and looks at me – he KNOWS!

Admittedly, I am exhilarated by this conflict of emotion; this bliss and shame I feel simultaneously. It is in this moment of lovely ambivalence that I decide it is time to buy my $75 concert ticket – no price is too high for such a sacred affair. And then, realizing their show at Ridgefield Playhouse falls on June 29, I am devastated.

While Jakob Dylan and co. will regale their audience with alt-rock hits, I will be far, far away, sulking on an air mattress in London. My high school dreams dashed forever.