REVIEW: How to Be a Rock Critic

All Lester Bangs wants to do is listen to his favorite record: Van Morrison’s 1968 masterpiece, Astral Weeks. If only he could find his copy. It’s got to be around here somewhere, beneath the splayed magazines, take-out containers, and just a few thousand other LPs. Such is the inciting dilemma of Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen’s one-man play How to Be a Rock Critic.

I couldn’t resist the irony of a dead white guy telling me how to do my job, so I got a ticket immediately. How to Be a Rock Critic is not a pedantic or instructional title, however, but one referring to an early Bangs article first published in a small-circulation college zine. The one-act play – starring Jensen as the ill fated and infamous music journalist – is largely concerned with its subject’s gospel. Its full title reads: How to Be a Rock Critic: Based on the Writings of Lester Bangs.

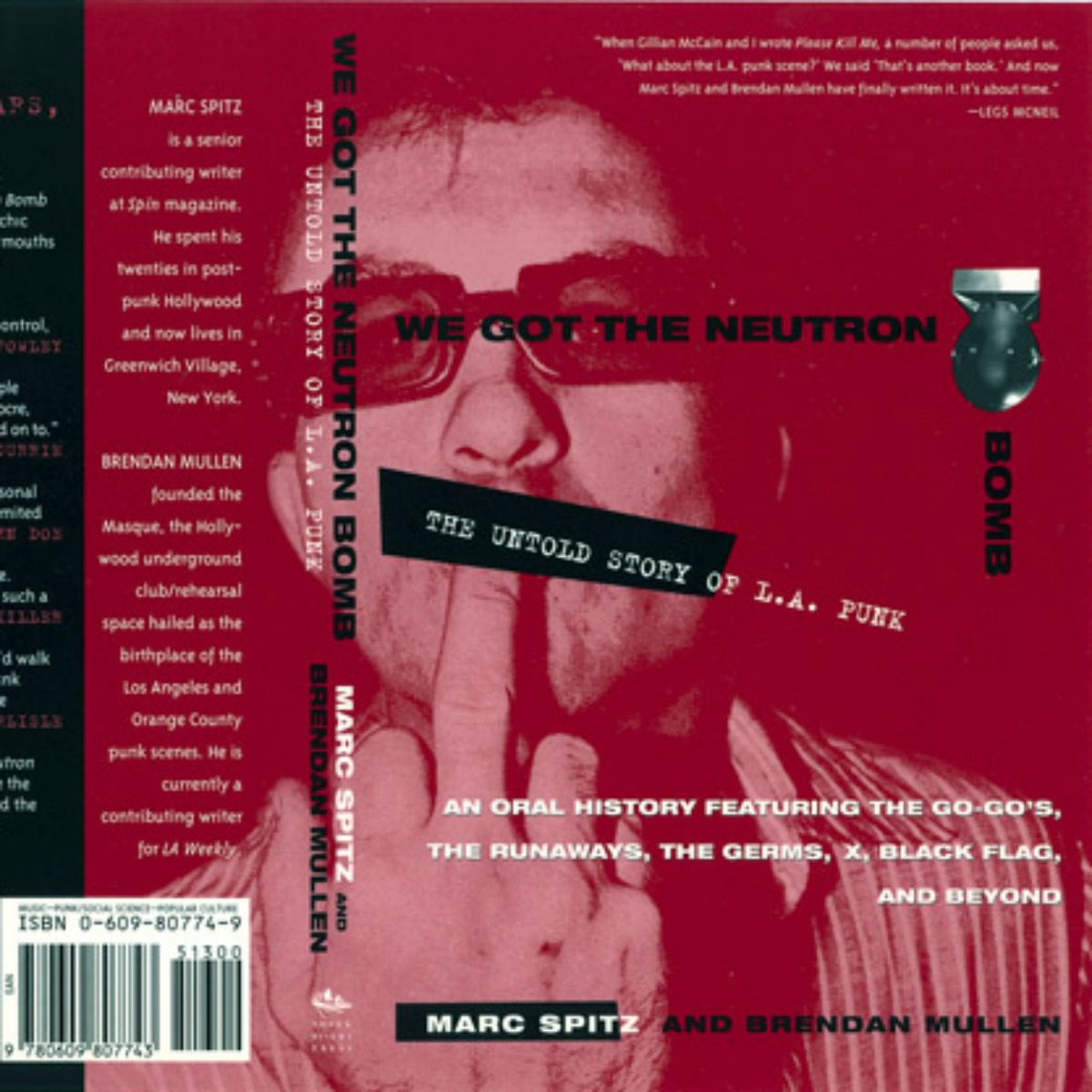

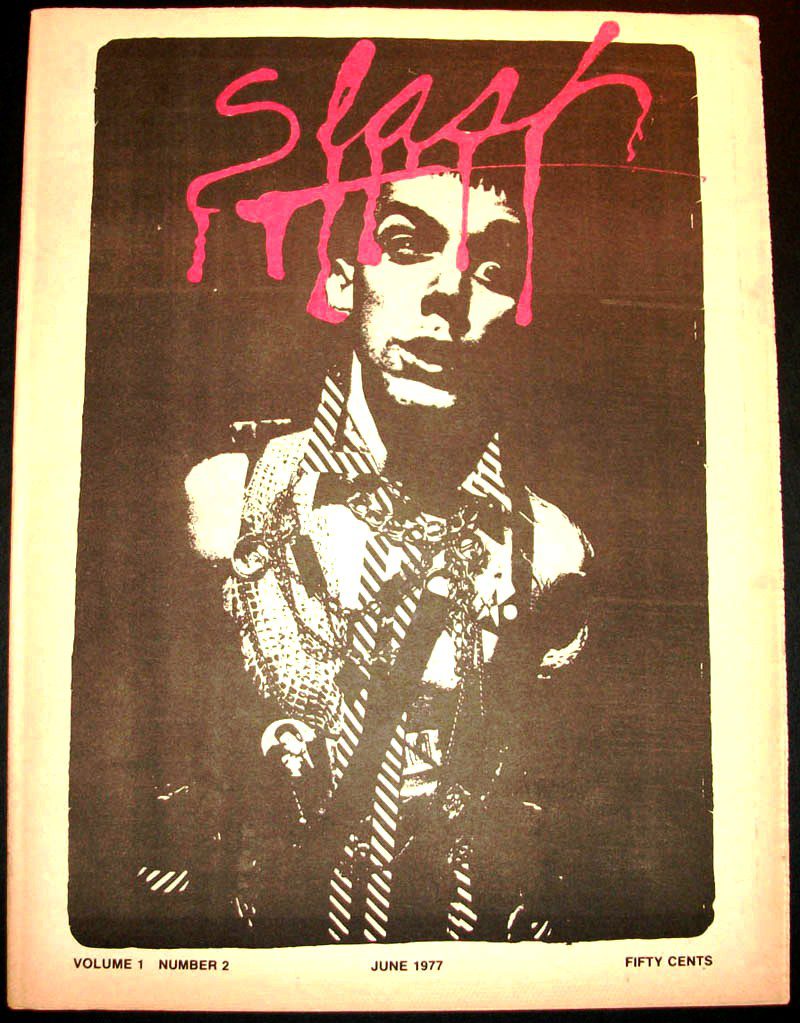

Part of what drew me to the play was sick intrigue; I was positive it would be a shit show, or reductive and formulaic at the very least. And I have my reasons. Historically the portrayal of rock ‘n’ roll via visual narrative has not gone so well. Flicks like The Runaways and What We Do Is Secret (about LA punks the Germs) fell prey to laughable clichés and fabricated idealism, imbuing their main characters with far more nobility than the real people deserved. These biopics are the inverse of books like We Got the Neutron Bomb, which was unmerciful in its portrayal of rock ‘n’ rollers. There was no glamour or honor when Bob Biggs of Slash Records said of the Germs frontman, “I once saw Darby shoot up with gutter water!”

If there is one thing worse than the fictionalized depiction of rock stars, it is the fictionalized depiction of writers. Whether it’s Javier Bardem’s anguished “poet” in Mother! or Tobey Maguire as Nick Carraway in Baz Luhrmann’s extended disco-remix of The Great Gatsby, the characterization of writers is often bloated with grandeur. Given that Lester Bangs was a stalwart of both rock and writing (not to mention bloated grandeur), I wasn’t sure if How to Be a Rock Critic could escape a trite fate.

A living room awaits at the Public Theater’s Martinson Hall on Saturday. It is littered with pages and beer cans and yes, stacks of records like angular layer cakes. If I didn’t know any better I would write this off as a stereotype, only it looks exactly like my friend’s apartment, and that friend is in fact a writer. It also looks exactly how my apartment would look if I had the freedom to live alone and be the slob I truly am. So they got me there.

The play begins with a grunt. Offstage bathroom noises collect our attention and soon enough Lester Bangs is before us. “Oh, fuck,” he says, before asking us to wait in his hallway for just, like, 20 more minutes while he finishes “this review.” “Ok… ” He stalls, “What about 15 more minutes?” To appease us he doles out magazines from a milk crate, and chucks cans of beer to a lucky few. In this little preamble, one thing is quickly established: Jensen-as-Bangs is one charming motherfucker.

Bangs entertains us briefly, rattling off motor-mouthed nonsense and informing us that he’s been up for 32 hours straight. He’d love to stay and chat, but he’s gotta “finish this review.” Stumbling over landmines of albums, he urges us to talk amongst ourselves. He reaches his desk, yanks an old page from his Smith Corona typewriter, and does exactly what you think he’s going to do with it.

I would like to see one portrayal of a writer, just one, that does not involve a sheet of paper being crumpled up into a ball and hurled across the room. Piss on it, eat it – set it aflame on your stove for god sakes – just please don’t crunch it into an angry little ball and toss it behind your back. When a new sheet is rolled into the machine Bangs stalls. He huffs, and puffs, and bangs on the keys. When the words still won’t materialize, he concedes. “Fuck it… let’s listen to some records!”

Within its first ten minutes, How to Be a Rock Critic erects two totems of Lester Bangs that will duel for the rest of the play. The first being Bangs as critic, fan, and fanatic. The second: Lester Bangs, tortured writer. I’m a fan of the former guy. Jensen’s ability to distill Bangs’ impassioned and vast catalogue of music criticism is admirable. His monologues are delivered with the same dizzying wit and lightning-speed stream of consciousness that Bangs was known for, and the amount of writing Jensen has synthesized is downright impressive.

Blank and Jensen spent years getting in touch with the Bangs archive, reading, researching, and turning thousands of pages of print into a play. Their success in shaping Bangs’ voice for the stage might have something to do with the duo’s background in acclaimed documentary plays like The Exonerated, which grew from firsthand interviews with over 40 released death row inmates. What shines in How to Be a Rock Critic are the long-winded, multi-syllabic manifestos on music, rock stars, critics, James Taylor (who Bangs so famously wrote should be “Marked for Death,”) childhood, girls, fandom, and of course, Van Morrison.

Bangs’ hunt for Astral Weeks punctuates the entire play, acting as the hub connecting countless spokes of praise and diatribe. It is the talisman he needs to justify his claims about art, and if he could only “just find this record, [fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][he] could show you!” When Bangs is talking about music, you believe his every word. There’s a contagious excitement Jensen conveys while putting on records and churning out rants, the same excitement Bangs was known to infect people with. The little details in Jensen’s performance, like cueing up a Carpenters album and slightly gesturing toward his favorite part of the song with raised fingers, are nuanced and spot-on.

Like Bangs himself, the play is charismatic, funny, and absurd, but at times deeply flawed. It is well known that Bangs died of an accidental pill and NyQuill overdose at age 33. His party animal habits and taste for drugs were as famous as his hatred for Led Zeppelin. This dark side of Lester – that “tortured writer” side – surfaces in my least favorite parts of the play. It’s not that I mind darkness, but Jensen’s rendering of Bangs-as-cough syrup philosopher can feel degrading at times. His sermons on writing feel like they were written by a writer, and not necessarily in a good way. I was reminded of Jeffrey Sweet’s introduction to his book, What Playwrights Talk About When They Talk About Writing, at one point. Namely that, “Playwrights don’t talk about writing with each other much.” Elvis Costello is often credited as saying, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” I say writers writing monologues about writers talking about writing is like a man self-addressing his dick pics.

There is also the issue of pandering. Several times throughout How to Be a Rock Critic, Jensen begins a sentence, only to trail off expectantly so the crowd can fill in the blank for him and pat themselves on the back. It’s a gross little episode of rock ‘n’ roll trivial pursuit that probably pissed off me and me alone, because I’m a critic (and nobody likes a critic). I cringed when Jensen began a story about “a club called???” And the audience dutifully answered in unison, “CBGB!!!” “That’s right! CBGB!” he said with the intonation of a children’s show host. Little things like this, of course, do not amount to a bad play. Nor do Jensen’s depiction of Lester’s tantrums, or scraps of monologue that grated my skin with their commoditized dissent. These are matters of taste.

In a final, half-hearted attempt at finding Astral Weeks, Lester Bangs fishes the LP out of another record’s sleeve. He’s on the floor. After gabbing for 80 minutes straight – pausing only to guzzle beer and two bottles of cough syrup – he toppled over and landed in a pile of 12”s. We’ve heard about his overbearing mother, he’s lamented the death of his father, and he’s reduced Elvis Presley to two identities: “Force of nature… and turd.”

Bangs strolls over to his turntable with the rescued wax and cues up “Cyprus Avenue.” At long last, we can understand what all the fuss is about. For me, it’s easy to understand. By a sheer stab of coincidence, Astral Weeks is one of my favorite records, too. There was a period of time during which I listened to it at least once a day, and it would certainly be in my luggage en route to a desert island.

In these final moments, Jensen and Blank (and I suppose Van Morrison) have nailed the spirit of Lester Bangs, and all the things he sought in music. But what was that? In 1980, Lester Bangs sat for an interview with his pal Sue Mathews, who asked him, “Are you aware of changes in the sorts of things that you look for as a critic? Or in the way that you listen to music?” “Hmm,” he said, “that’s a good question. Basically all I look for is passion, and I don’t care what form it comes in.”

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]