ONLY NOISE: Why I Talk to Jim

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Beth Winegarner revisits her teenage obsession with infamous Doors frontman Jim Morrison, an archetype of both the sensitive poet within herself and the thorny men she encountered.

The day before I discovered Jim Morrison, I broke up with my first serious boyfriend. We’d met in high school, and got together when I was 15 and he was 18. He was impossibly tall, lanky, with a hooked nose, a puff of curly hair like a Q-tip, and pale, watery blue eyes. I wasn’t attracted to him – aside from his pale, ropy biceps – but he was sweet and kind. He was a foot taller than me; I had to stand on benches or stairs just to kiss him. The summer we started dating, he took me out to the beach and for walks in the woods, and to his house, where his bedroom was a small trailer separate from the main house. In that little fiberglass cocoon, Led Zeppelin and the Scorpions shaking the radio, we made out a lot, and went further.

At first, I wanted it – the waterfall of longing, the fumble of curious fingers, the ache between my legs. But it hurt, even more than I thought it would, and I hated it. I didn’t want to go any further; I wanted to stop and be held. I wanted to hear that it was okay, that it was my body and I should trust it to know what was right. Instead he pushed me, begging and pestering, his complaint of blue balls suggesting I owed something to him. I caved, thinking that a little bad sex couldn’t be worse than the endless badgering. I gave him what he wanted with my hands or my mouth. I gave him what he wanted while I left my own body, so I didn’t or couldn’t feel. Because what I didn’t or couldn’t feel wouldn’t hurt me. I spent so many afternoons in his trailer, leaving my body.

I began to pull away from him, though neither of us understood why. He was oblivious; I had abandoned myself. We spent less time at his house and more time in the woods, or driving the tree-lined backroads of Sonoma County. As he steered his rumbly, faded copper Pinto, I could look out the passenger window, away from his face and his long, probing fingers, into the shadowed spaces between the redwoods.

It was Valentine’s Day when I realized I couldn’t stay with him anymore, but it felt cruel to break up with someone on a holiday dedicated to romance. So I waited a few days, invited him over, and told him on the wide front porch of my house, under my mom’s wisteria vines. I don’t remember what I said, aside from vague promises to remain friends. I know he cried. I probably cried. And when he left, my body felt weightless, felt like nothing at all.

The next day, skimming through the newspaper, I spotted an article about a new book: Wilderness: The Lost Writings of Jim Morrison. I’d been writing poetry for a few years by then, and felt a tug at my gut at the idea of a rock-god-turned-poet. I asked my mom if she’d buy the book for me. She offered a compromise: an advance on my allowance, so I could buy it myself.

A few hours later, scanning the spines in the poetry section of a bookstore, a shiver washed through my body as I found Wilderness on the shelf. I pulled the skinny, hardbound volume away from the others, inhaling the new-book smell of paper and ink as I opened it to a random page. The poem I found spoke of infinite power – the opposite of what my aching self felt in the aftermath of that relationship.

I can make myself invisible or small.

I can become gigantic & reach the

farthest things. I can change

the course of nature.

I can place myself anywhere in

space or time.

I can summon the dead.

I didn’t know it yet – and wouldn’t, for many years – but my interest in Jim Morrison was a sign of my own demons being born.

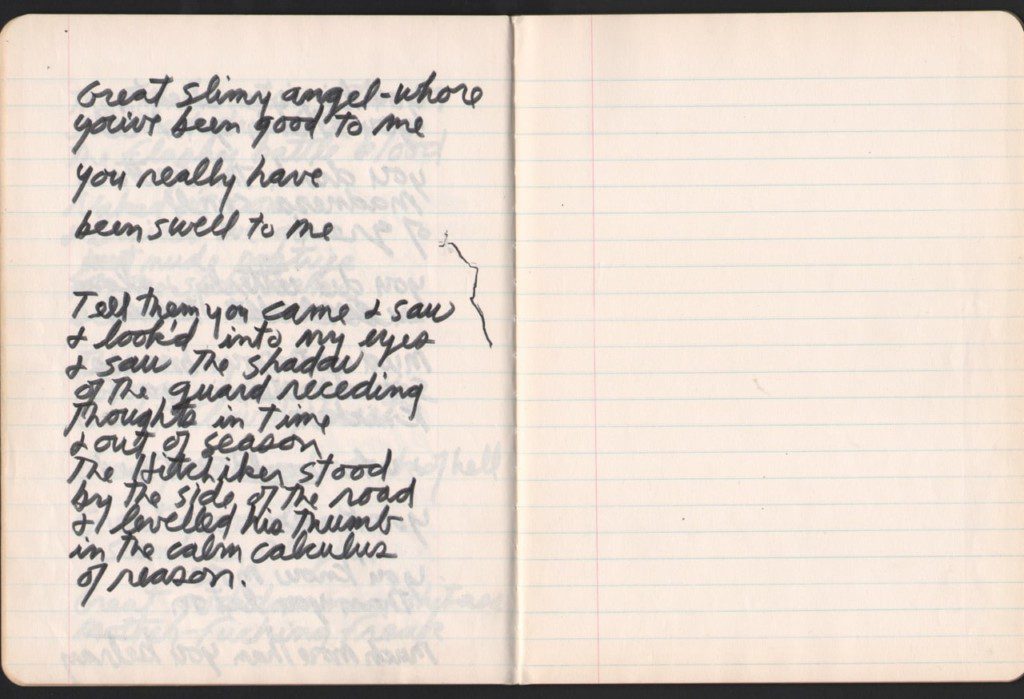

I closed the book, hugged it to my chest, and took it to the register. At home, I laid on my threadbare quilt and twisted my hair around my fingers as I read, simultaneously drawn in and mystified by Jim’s stream-of-consciousness surrealism. “If only I could feel the sound of the sparrows?” “I received an Aztec wall of vision?” I read and re-read the poems, puzzling them out, studying the ones represented in Jim’s slanted, loopy scribble.

His poetry was baffling, too abstract for my teenage mind, but I didn’t abandon him; I started buying Doors albums instead. I also devoured No One Here Gets Out Alive, the flashy biography of Jim’s life written by Doors publicist/fanboy Danny Sugerman and journalist Jerry Hopkins. I read the book while listening to their music, thrilling to hear Jim’s croons and yelps as I soaked up his collision-course life. And I began writing letters to him, calling him “James,” feeling that he was too godlike for me to call him something as ordinary as “Jim.”

Dear James,

There is a poster of you hanging from my wall, at the foot of my bed. When I wake up I can look at you – when I write I can look at you as well. Last night I wrote a poem and your presence inspired a piece of it.In his eyes there burns

A calm, shivering flame

Beyond which the seas rise and fall

And rise again

A long tendril of curious hair

Falling fragrantly

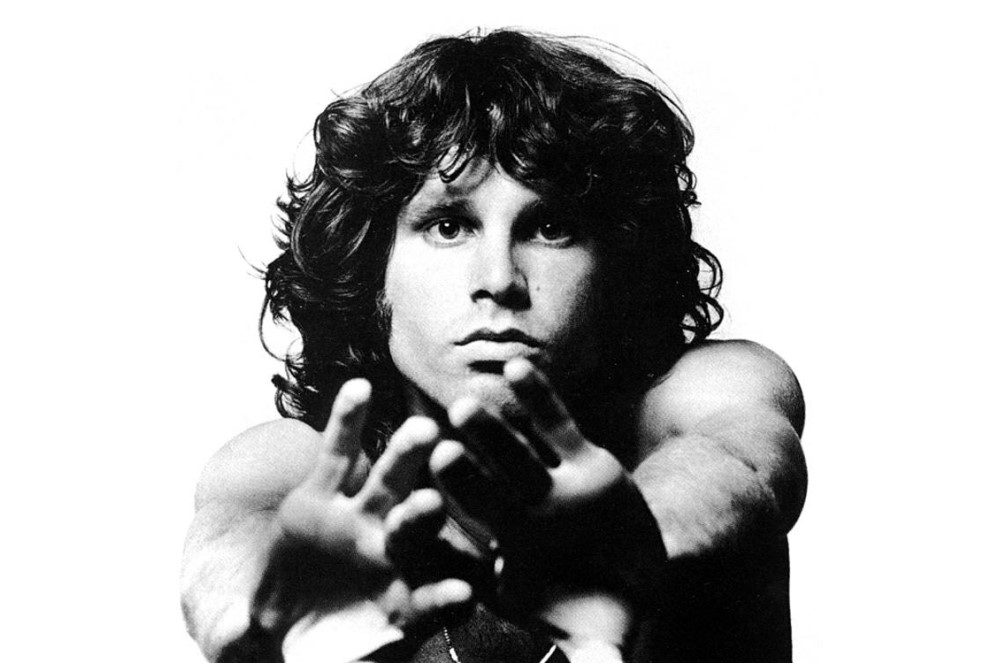

On the shoulder.When I walk into my bedroom, I see your face looking back. Your eyes are so troubled and wide and innocent-looking. I don’t think you were as innocent as you seemed. Why did you never smile in pictures? Your arms are stretched towards the camera. Why? Were you trying to push it away? Were you trying to swim into it, to escape from reality?

My bedroom walls were plastered with posters, flyers for local rock shows and pictures of pop stars torn from magazines. Duran Duran, Madonna and Cyndi Lauper were still among them, but an oversized black-and-white poster of Jim took a prime position at one end of my bed, where I could look up at it while resting. In it he was bare-chested, thick hair curled around his face. His dark eyes fixed on me. A thin, beaded necklace hung from his neck, the only indication that he was, indeed, part of the 1960s rock scene, and not some Roman god back from oblivion.

Jim was unlike anyone I’d had a crush on before. He was mysterious and a little dangerous, even 18 years after his death. I studied the shadow of his brows, cheekbones, the curve of his shoulder, imagined what his full lips felt like. I wondered: what made him drink so much, take so many drugs, die so young, when he seemed so full of energy? Could I have helped him, taken care of him, kept him safe from his demons?

There are moments when I was sure he would have loved me. I was small, red-haired, porcelain-skinned and smitten with his poetry, just like his girlfriend, Pamela. I could even believe I was her reincarnation – if she hadn’t died of a heroin overdose the year after I was born. I was also like his pagan wife, Patricia: red-haired, witchy, a writer with a fondness for pop music. I could tell – I was his type.

Dear James,

I wonder where you are now. Who are you now? Do you even believe in reincarnation? I do – and I am pretty sure that your soul is walking the Earth today, probably in someone about my age. You could be someone in my school, my orchestra, someone in this area. But you might not even be in this country, you may be a small child, and you may not have been reborn yet. Or maybe your soul’s life-cycle has finished, and you will not be born again. I wish I only knew. I do know, however, that if Fate proves that I am supposed to meet you, whether for the first time or again, then I will. It will be done.

From a young age, I’d learned to put other people first. I was quiet, shy, obedient. I liked rules; I felt safe knowing I was doing the right thing, and it was an easy way to please the grown-ups around me. I earned extra praise (and sometimes cash) for good grades, so I poured myself into schoolwork. Each afternoon, I walked the dusty path home from school, sat down at the wide dining room table, and bent over my books until my homework was done.

In my preteen years, I fell in love with music and writing. Diaries and poems let me share the feelings I was too shy to speak aloud. And music offered a context for my ever-shifting feelings, plus space to dance and celebrate when I felt good. I devoured issues of teen magazines like Bop and Smash Hits, poring over photos of Duran Duran and Madonna while their music cascaded from my stereo. The boys in Duran Duran were so beautiful; I used to list them in my head from cutest to least-cute: Simon, John, Nick, Roger, Andy. With their teased hair, smooth skin and silly banter, they seemed wholesome and fun. Perfect imaginary boyfriends.

Although both my parents were loving and kind, something subtle shifted when my body started to change. My dad stopped touching me; he wouldn’t even hug me anymore when I was upset or hurt. Instead, he showed his love by cheering me on in school and making sure we had everything we needed. But I missed riding on his shoulders, sitting in his lap, snuggles and songs at bedtime. Part of me wondered if my new breasts and hips somehow made me untouchable. Unlovable. But once I entered high school, my body made the boys stare a little longer, and talk to me in ways that made me think they were interested.

I wanted that attention so badly, and it cut deeply when I discovered, with those first sexual experiences, that I wasn’t ready for it. Or that a boyfriend who claimed to love me would trample my wishes to get what he wanted.

My best friend knew more than almost anyone about the relationship I’d just left, but she didn’t know much about the sex. I didn’t tell her how much of it had been against my will. Partly because I just thought it was bad sex, nothing more; partly because she was having sex, too, and I wasn’t sure if I she would judge me for doing it wrong. And I didn’t tell any of the adults in my life, especially my parents. They would be disappointed and angry with me for having sex so young. I couldn’t face their disapproval when I was already hurting from the breakup, and from something else inside me I didn’t recognize. Whatever it was, it was huge, sad and wordless, and it left me longing for something I couldn’t put my finger on.

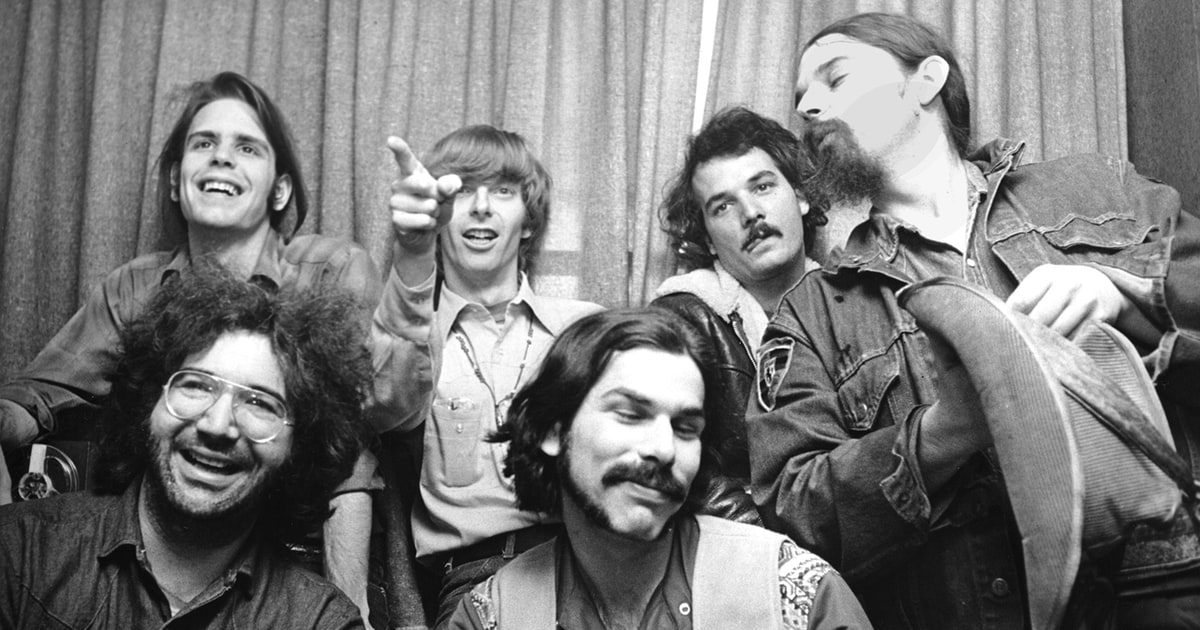

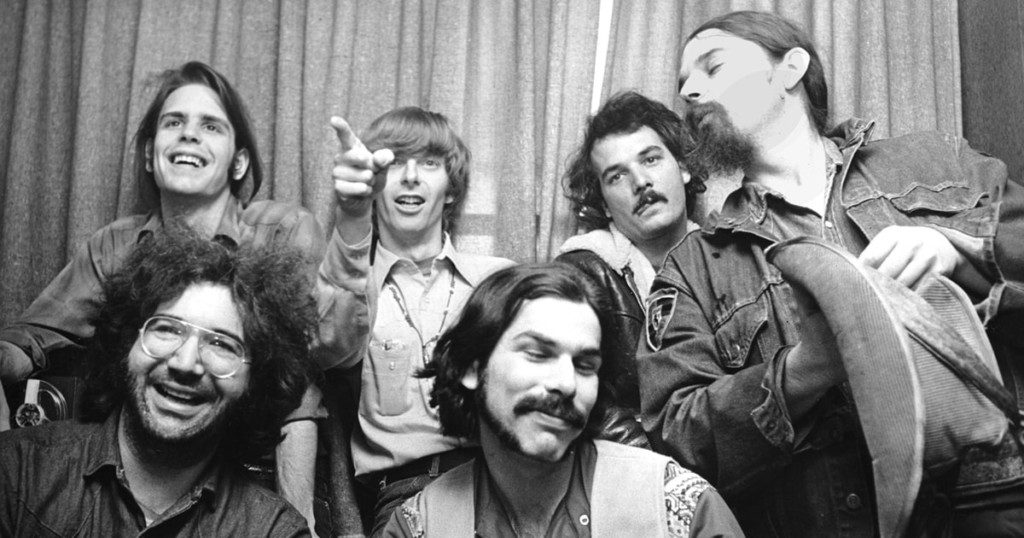

Jim had no drive to please the people around him. He was a rootless military brat who fell in love with the Beats and styled himself after Jack Kerouac’s rambunctious buddy, Neal Cassady, before taking cues from experimental theatre and nihilist literature. He often claimed that the defining event of his early life was passing a traffic accident on an Indian reservation, where the souls of the dying entered his body. His songs lingered on death, escape, transcendence, and women who loved to get high. Reading No One Here Gets Out Alive, I adored the stories of him on the beach, singing poetry to his friend Ray Manzarek, who became The Doors’ keyboardist; of his rooftop squat where he slept, drank and wrote; of his shyness, so painful that he sang with his back to the audience during the Doors’ earliest gigs. His excesses – his womanizing, his habit of consuming mind-melting quantities of psychedelics – seemed charming, even quaint; a relic of 1960s experimentation, even as the book described his bandmates’ concerns about his behavior.

I was just the opposite: quiet, organized, orderly. I avoided high-school parties because I was scared of losing control on alcohol or drugs, and of seeing my friends acting funny while drunk or high. I didn’t want to see their masks slip – or my own. But here was Jim, singing about the killer who took a face from the ancient gallery before threatening to kill his father and fuck his mother. It unsettled me, but I also needed it somehow.

Jim wrote copiously in notebooks he took with him everywhere, and kept them in a strongbox he called “127 Fascination.” I adopted this practice immediately, filling notebooks – one of which I named “128 Fascination” – with teenage poetry, quotes from friends, photos, sketches, and letters to Jim.

Dear James,

How did you feel when Pamela entered your life? Was she just another girl, or was she special right away? I read an article that called her “a young, red-haired art-school dropout from Orange County who stumbled into one of the Doors’ earliest nightclub gigs on the Sunset Strip and promptly fell in love with the good-looking singer in the band. It went on to say that you took her home that night, and ever since began introducing her as your “cosmic mate.” Is this true? How did you feel that first night, I mean, did you know? Soulmates you may have been, but how long did it take for you to realize it?I look at you, and I, myself, feel drawn to you. There is a mystique about you that draws even the most timid of women, even the most skeptical. But you used that to your advantage – indulging your wildest fantasies because you knew they were willing, trying to have as many women as you possibly could because they didn’t refuse, because they wanted you. Sex is an escape, which is as volatile, as addictive, as any drug.

As a teen, I didn’t recognize his abusive side. The fights with Pamela. The relentless failure to show up on time for rehearsals or gigs. Performing drunk, high or both, and attempting to provoke the crowds to riot. He lived his life as a kind of social experiment or performance art, and it was years before I understood that men like him aren’t to be trusted.

Jim was the first of his kind that I had a crush on, but he wasn’t the last. Soon I had eyes for Axl Rose, the wild, unfiltered frontman for Guns N’ Roses, and the similarly unhinged Sebastian Bach, the beautiful lead singer for Skid Row. After I stopped writing letters to Jim, I started writing letters to Axl, and longed for others like him. I wanted these men’s darkness, their drama. Their tempestuousness and talent made my blood hum and limbs loosen. I mistook their raw, unfiltered diatribes for openness and vulnerability. Their willingness to be angry and unacceptable stood in for my own as I wrapped myself in fear and silence, pretending I was okay.

My ex wasn’t much like these rock stars. But he had done something that made me feel deeply unsafe, that violated my right to decide what happens to my body. Years later, I realized that my attraction to Jim was the first sign of that wound. “Many traumatized people expose themselves, seemingly compulsively, to situations reminiscent of the original trauma,” writes trauma expert Bessel Van Der Kolk. Sigmund Freud thought people repeated situations and relationships to try to gain mastery over them, but that’s not usually what happens. Instead, the repetition re-traumatizes survivors and hurts those around them, Van Der Kolk said.

My path wasn’t so straightforward. The next year, I fell in love with a guy my own age, who was kind and gave warm, strong hugs that squeezed goodness into my body. We had a lot in common, down to our fondness for thrash and funk metal, and rain in the forest. He didn’t push me to have sex. When we did, on weekends in his king-sized bed with redwoods outside, I would tremble and sob and have to stop. My body was beginning to tell me the story of what I’d been through. He held me through it, until my tears waned and the terrified parts of me felt safer again.

But the darkness was never far from the surface, and Jim was a constant companion throughout high school. Over time, it became less of a crush, more of a desire to be like him, somehow: raw, literary, brave, honest, but without all the mind-altering substances. I couldn’t let people see the wounded part of me, couldn’t let them know I didn’t have my shit together, so I lived it through Jim. I started writing short stories about damaged young men – always men, somehow – who did too many drugs, drove too fast on backcountry roads, took their own lives, or were literal murderous vampires. I rewrote those roads I once drove with my ex, and littered them with terror, fear and shadow.

Later, in my 20s, those longings spilled over into my personal life. I dated a handful of guys whose long hair, good looks and damaged souls sucked me in, like a 5-year-old to a sack full of candy. There was the one who’d stayed home from school as a childhood to keep his mother from killing herself, a passionate lover who would pound his head on the wall when he did something wrong. There was the one who’d been abused by his uncle, who drank until he passed out every night, but woke up at 3am wearing the face of that wrecked little boy. And the one who thought he was a spiritual guru, complete with visions of parallel worlds, but who turned out to be delusional. I cared for them, thinking I was giving them the mothering they’d needed but never got. Instead, I was trying to give them what I most needed myself: unconditional, gentle love, someone to help that frightened girl-child inside me feel safe so she could finish growing up.

It’s 30 years later, and the shadows haven’t left me. I see Jim Morrison now for what he was: a flawed, damaged, charismatic guy who flamed out far too early. Inside me, still, is the teenage girl who sought refuge in his darkness, a thick cloak of turmoil that masked my own. But I’m working to remember the girl I was before all that: the Duran Duran and Madonna girl, the curious, shy and trusting girl. Jim had someone like that inside him, too – a quiet boy, curious and bookish, who built up layers of armor to survive being moved from place so many times as a kid. A little boy so shaken by the sight of a violent highway crash that those ghosts rattled around inside him for the rest of his brief life. These days, I’m drawn more to that kid, whose “fragile eggshell mind,” as Jim once described it, was cracked before he knew how to handle it. The girl in me knows just what that’s like. She’s still inside, somewhere, wondering why all the lights went out.