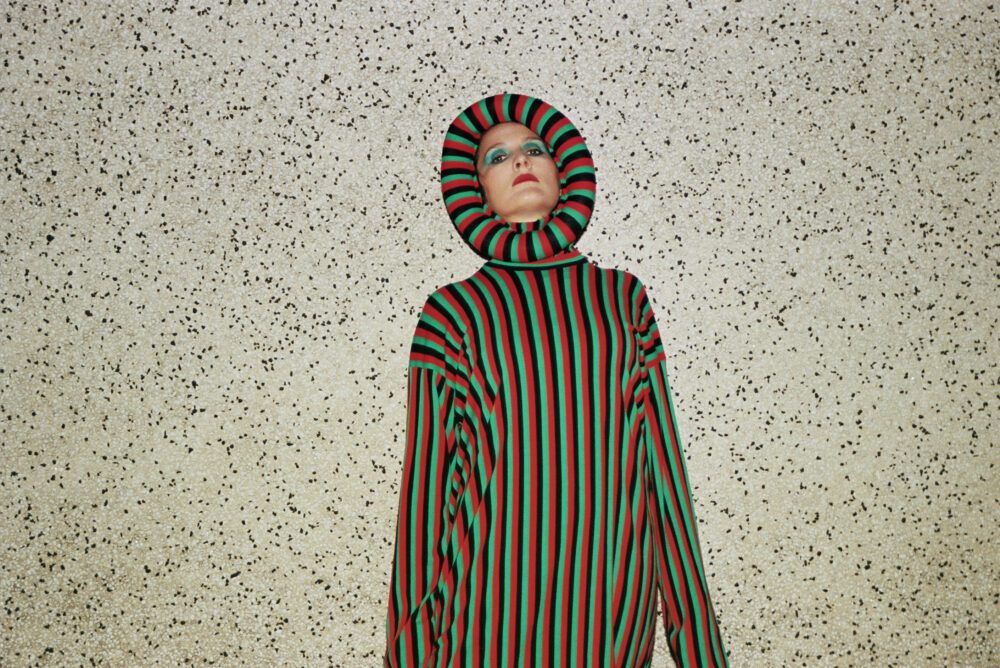

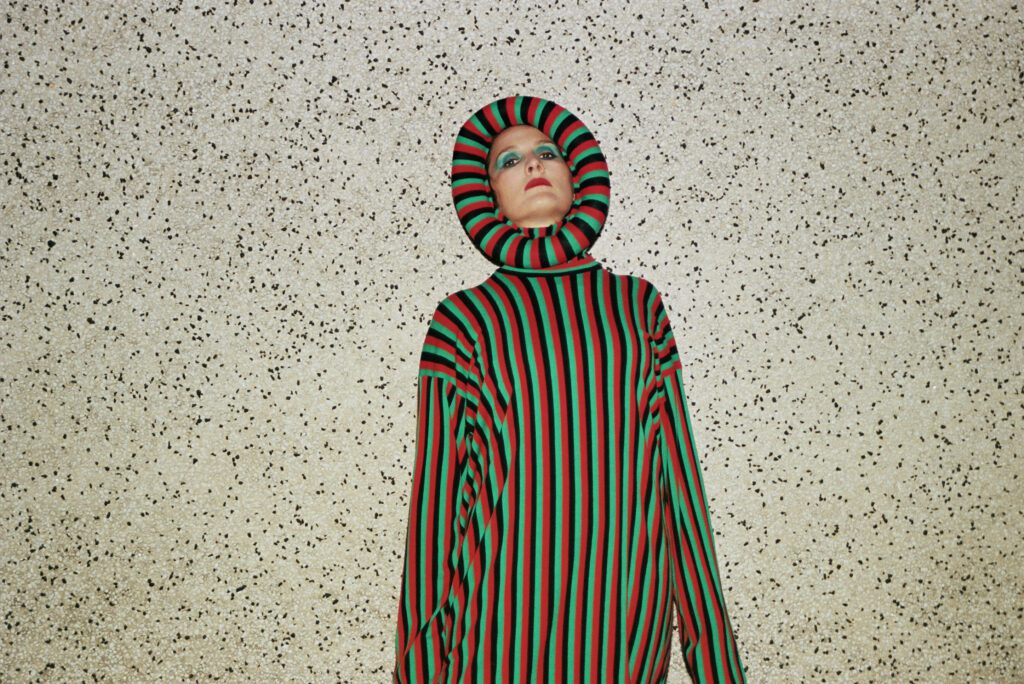

Cate Le Bon has a knack for poetically weaving dualities: history and imagined futures; progress and destruction; the personal and the collective; the orderly and being “tethered to a mess,” as she sings on “Moderation” from her latest LP Pompeii. From a bedroom in Cardiff last year, she made her sixth album, out February 4 via Brooklyn imprint Mexican Summer, with collaborator and co-producer Samur Khouja.

Since September last year, she has returned to her adopted home, the US. When we chatted last December, she was in Topanga, working with Khouja again to produce Devendra Banhart’s album after playing a festival in Marfa.

“We’ve rented a house that we’ve turned into a studio. It used to belong to Neil Young in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” she tells Audiofemme. “Devendra and I are both living and working in the house. It’s just so easy and lovely. We’re having a dreamy time. There’s not many people you can live and work with and still look forward to seeing in the morning.”

She has plans to make another record this year, on her own terms rather than under the restrictions imposed by border closures and lockdowns, but producing for other artists is also on her agenda.

“It’s just joyous to see other people’s process and it’s a real beautiful thing to trust someone with your record,” she says. “I’m not looking to do it full time but there’s certain people that I love working with and will always have the time to do that.”

Topanga is a long way, geographically and metaphorically, from the Cardiff bedroom where Pompeii was recorded. The texturally-rich tapestry of saxophone, strings, synths, bass and multi-track guitars is the most danceable excursion into existential inquiry, wrestling with faith, intention and purpose. Le Bon’s catalyst was Brazilian-Italian architect Lina Bo Bardi’s 1958 essay “The Moon,” in which she laments the perversion of dominance, control and technology in the pursuit of knowledge.

“The underlying theme of the record is: you will be forever connected to everything,” Le Bon explains. “It was this Lina Bo Bardi essay that I’d read… about how man will destroy everything, really, in this attempt to eat the moon, and nothing’s changed, and I suspect nothing will change. All these incremental changes that have been made under the banner of progress is probably why we’ve ended up in a global pandemic, with everything shut down and hundreds of thousands of people dying. There’s this sense of being connected to those very first decisions that were made that started the wheels turning… about knowing all that and still wanting the things that you know are bad and contributing to [destruction].”

The Welsh artist had been demoing Pompeii in Joshua Tree in 2020 with repeat collaborator, drummer and producer Stella Mozgawa but an invitation from John Grant to produce his album Boy From Michigan took both her and Mozgawa to his adopted home of Iceland. She had been in Iceland when the pandemic began closing borders in March 2020, choosing to remain and continue working, though Mozgawa took the last flight back to Australia.

“When I was working in Iceland and everything shut down, I was lucky because it’s quite a fortunate place to find yourself when a global pandemic kicks off. I was somewhere safe and I was earning money, which seemed to be a massive problem for friends and family back home,” she remembers. “I was locked out of America and my partner [Tim Presley, collaborator in Drinks] who lives there, we’d just bought a house and I couldn’t get back into the States. My instinct was to get home to Wales, to get home to my mum and dad and my sisters, my best friends from childhood and be amongst them.”

She returned to Cardiff in May 2020 after two and a half months in Iceland. Pompeii was created not only in her homeland, but in the same Cardiff house she lived in 15 years ago, in her late twenties. That would have been around the same time she released her debut album, Me Oh My in 2009, a year after her EP in Welsh language Edrych yn Llygaid Ceffyl Benthyg (Looking in the Eyes of a Borrowed Horse).

“I think [Pompeii] certainly captures the time and everything that was going on in my small little world. Everything was put into that record and it’s beyond words to try to distil everything that you’re feeling when everything is unstable and the future is dark. So, to be able to really put that into music was cathartic. It was all I could do at the time,” she says.

Khouja was her trusted accomplice, and the two worked diligently for months within the Cardiff house that Le Bon knew so intimately – every light switch, every mirror, every creaky floorboard.

“It’s not a bedroom record in the traditional sense,” Le Bon acknowledges of the luscious, textured sounds of the album. “We had a lot of gear and Samur is the best engineer you could dream up.”

She first met Khouja at his recording studio in downtown LA – he was engineering her third album, Mug Museum. “I just really loved the way he worked,” Le Bon says. “It’s always forward motion with him. He’ll never say ‘you can’t do that’ or ‘that’s ridiculous.’ He’s so into exploring and his curiosity is so infectious.”

From the opening strum of guitar on “Dirt On The Bed,” there’s a sense of languid luxuriousness to the sound. “That was the first song that we tackled, Samur and I together, and it was a song that was born from something else then reduced to a one-note bass synth line that everything else spring-boarded off,” she says.

Strings writhe around each other, resonant and metallic at the top end but accompanied by a deep twangy bass. A resolute sigh of brass rises and falls away like the shrug of shoulders. Like walking deep into a forest, the harmony of animals and trees, rivers and undergrowth has an organic symphony effect. Le Bon, central but unimposing, is the guide to this raw, unexplored new territory.

“Moderation” bounces along, guitar spraying its sunny beams out over a warm, deep bassline. Le Bon’s radiant falsetto and sweet harmonies rise over the track in their glorious multi-coloured beauty like a pastel, shimmering rainbow. “French Boys” is a simmering haze of ‘80s-style synth keyboards and saxophone with the vaguely disjointed, crystalline half song-half spoken word ode to les garçons.

“It’s a song about the cliches drowning you, I suppose,” Le Bon muses. “The guitar sounds on it are so beautiful to me. The guitars are running through about eight different pedals and some magic Samur’s working. That was a bit of a labyrinth to record and work out all the paths.”

Le Bon plays all the instruments on the album, except for the saxophones (care of Euan Hinshelwood and Stephen Black, both members of her live band) and drumming by Mozgawa (of course).

Stella Mozgawa’s minimal percussion, complementary and organic, was provided from her homeland in Australia. Fresh from working with Courtney Barnett on Things Take Time, Take Time, Mozgawa is in her element when partnered with visionary women who are confident in what they like and how they want to convey their vocals and musicality, but are nevertheless open to guidance and influences.

“She’s so accomplished on the drums, it’s insane. I tear up watching her play drums. She’s unbelievable but she doesn’t have an ego. It’s like she’s got nothing to prove and she never reacts. She always responds to people in the studio, it’s always really thought through. She’s just a true master, phenomenal to work with,” Le Bon says. “Stella played a huge part in a lot of things I’ve done in the past five or six years. Working with her is one of the greatest joys. She’s phenomenal… it had to be her drumming on this record. She was in Australia and we were in Cardiff doing sessions on Zoom chatting to each other, then Samur was linked up to Pro Tools. It was not the same as being there but it was an amazing second option.”

Mozgawa was the drummer on Crab Day too, Le Bon’s fourth album, in which she worked with Noah Georgeson and Josiah Steinbrick again – the producers of her 2013 album Mug Museum.

Pompeii arrives only two years after 2019’s Mercury Prize-nominated Reward, her first album after signing with Mexican Summer. Since, she’s performed with composer and musician John Cale at the Barbican, backed by the London Contemporary Orchestra. It is the cherry on top of a catalogue of really candid, cadenced and – ultimately – beautiful albums. A tour in support of the record kicks off in Woodstock, NY on February 6.

The process of creation was Le Bon’s coping strategy, and she admits that it was a time – as it was for many – in which the lack of a certain future was both reassuring and scary. That duality is played out in the musical and lyrical dynamics, as listeners will discover for themselves.

“You’re processing all this stuff and music and writing is such a beautiful way of processing something,” she says. “The language of unsurety is quite a difficult code to crack, it’s kind of explorative and complicated and at times I just had to trust that something felt right… trusting that it was almost like a letter to my future self.”

Follow Cate Le Bon on Instagram and Facebook for ongoing updates.