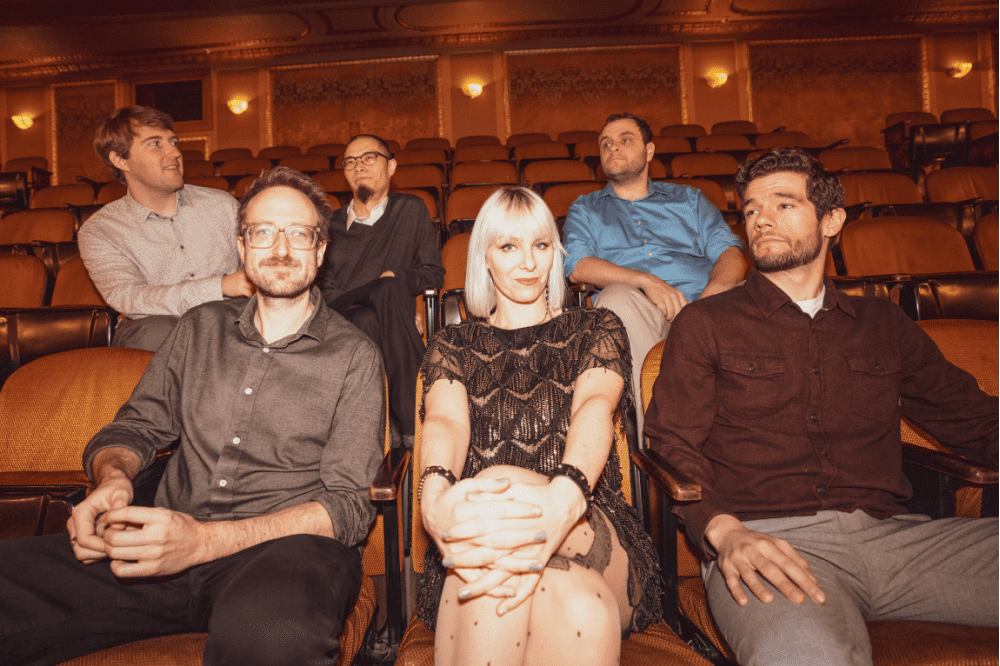

Jessica Dobson is a quiet giant of contemporary indie music. Along with performing her own material in Deep Sea Diver, Dobson has worked with indie music darlings like Beck, Conor Oberst, Spoon, and The Shins. And yet, if you said her name to the person next to you, they likely wouldn’t know who exactly she is.

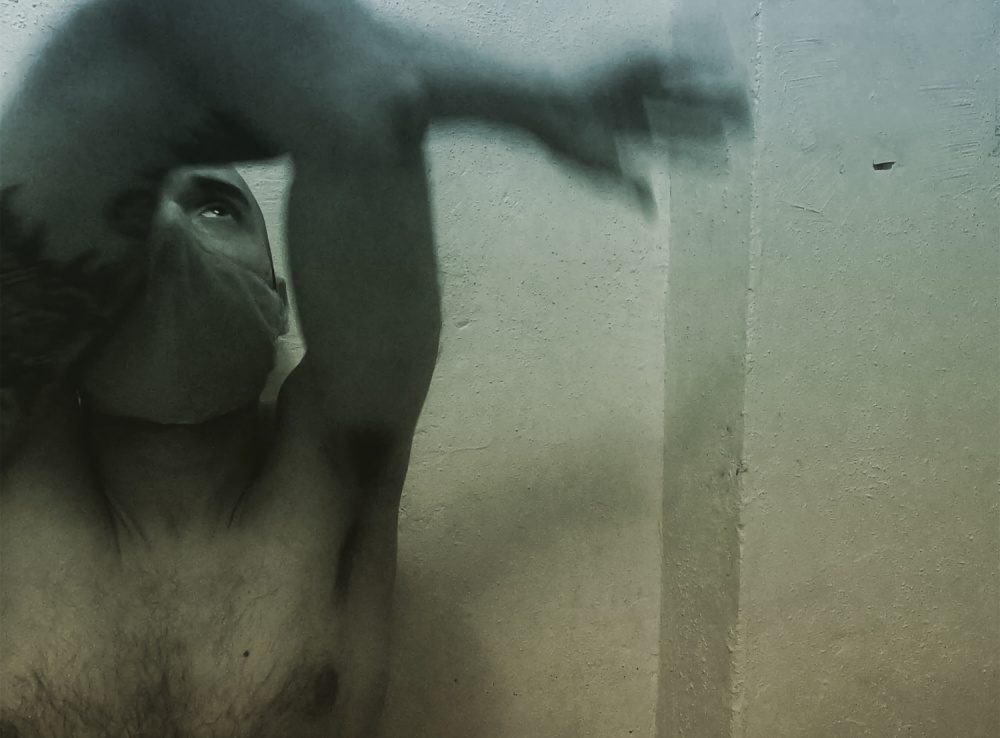

This needs to change, and with the October 16th release of Deep Sea Diver’s newest album Impossible Weight via High Beam/ATO, it likely will. Deep Sea Diver’s third album is emotionally ferocious and tender at the same time, capturing Dobson’s uncanny ability to create transcendent and distinct worlds with a well-honed ear for production, much of which she co-produced. Lyrically, Impossible Weight is spun from a complex time for Dobson, as she considered heightened anxiety issues, the death of a dear friend and collaborator, and long-standing questions about her identity.

AF: I know you were born in LA. When did you move to Seattle?

JD: I moved to Seattle in the very beginning of 2011. Before that I was living in Long Beach, California and I grew up in Orange County, then finally migrated up here. Peter Mansen, who’s my partner—we’re married and he’s also our drummer in the band—he’s from here. So, he was like, ‘Want a fresh start in Seattle?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, that sounds awesome.’

AF: You were signed by Atlantic at 19 years-old; was music, specifically rock guitar music made my women, in your life at a young age? How did you know this was a career that was possible for you?

JD: I did have examples. But I think at a young age it didn’t register with me to do it because I had gendered role models. I just saw an instrument and I was like yep, this is what I’m doing. It was more like following instinct at that point versus looking at something so I could have permission to do it.

AF: I love that you weren’t seeking permission. But, have you had any significant challenges in your music career because of your gender?

JD: I think that very often growing up there are definitely certain boxes that people tend to push you in and I was kind of set at an early age to not be put in those boxes. So, at the time there was a lot of like, acoustic female singer songwriting music out there—like in elementary school there was Jewel, and [others]—and I totally respect them but that wasn’t necessarily for me. I think I have always had an independent spirit when it comes to sound engineering and production, things that are kind of scary worlds sometimes for females because they’re worlds that are male-dominated. I was trying to peer behind the curtain from a young age and educate myself and other females who wanted to do the same thing. Not so I could be like “let me show you” but I think now I’m very passionate about demystifying a lot of those realms for female identifying people.

AF: I re-read a 2016 piece from The Stranger about your second release and the author called your time with Atlantic “ill-fated.” I’m wondering, was it really “ill-fated” or did it teach you something that you’re bringing forward with you?

JD: Signing that Atlantic record deal—it was ill-fated but also beautiful because part of [me] wants to learn and forge [my] way forward— I’m grateful that it happened then, not now. And so I think…the best thing about that time that was “ill-fated” was the rejection that I felt, the understanding of what was going on in my body—I was experiencing anxiety but I didn’t understand what that was at that time and now I have better language for that and better tools to deal with it. [There were feelings of] rejection and sadness and I didn’t know what I was doing, and I made this thing but it never came out. Maybe that’s a good thing and I was able to use some of that music to move forward and start Deep Sea Diver.

Now, even on a song like “Impossible Weight,” I think for a long time I was like, ‘That is so in the past and I don’t really care about it anymore [or want] to talk about it.” Even at some points, to be honest, I was just irritated, like why is it always being brought up in interviews? But it’s a good question, you know… Those moments in life, they do brand you in a certain way, and you can choose what you want to do with the pain and the hardships. For me, “Impossible Weight” was a song where I finally—it’s not all about Atlantic—but it is kind of like speaking to the gatekeepers and speaking to my younger self. You can’t please everybody, you can’t carry that weight. So now I feel more confident in who I am, what I want to do and where I’m going and where this band is going. And it feels really beautiful.

AF: I love the song, “Eyes are Red, Don’t Be Afraid.” I know that song is partly inspired by the Brett Kavanaugh trial; could tell me a little of your experience of watching that trial and how it informed the song?

JD: That song was written in the midst of a lot of things. So, it wasn’t directly inspired by the trial but I was definitely able to finish my thoughts and lyrics and intentions while that was happening.

That song was the first song I wrote after I attempted to record album number three twice. I was kind of flailing around creatively, emotionally, really trying to find my footing. I had quit smoking and Peter had as well, so when you and your partner have both quit and that’s something you’ve used as a crutch for a long time, you know, it’s like “OK, this is where I’m at, and it’s going to be a little dark for a while but I’m going to push forward.” That was the first song I wrote as I was in the middle of quitting, and I had these mantras I would say to myself, these very simplistic lines, like, “don’t be afraid, don’t be ashamed.” And when I would start to write, I just had to say those things because I wasn’t feeling them and I wasn’t feeling any color in the world.

And so, most of that song is very intimate and very personal to me and what I was going through, but then it became part of a broader narrative. This is in like the thick of the Me Too movement, Harvey Weinstein, Trump. We thought we had progressed but these are still the issues at hand, like are you kidding me? We still have to convince people to listen to you if you’ve been abused? It’s just wild and so unfair. As a woman I felt the weight of that. The collective weight.

Then, there was an article, I think it was in the New Yorker, a journalist mentioned how many bodies have to be thrown onto the tracks to build up to stop this train? It will take more sacrifice unfortunately to get anything to change. That finished my song for me.

AF: Does music help you do that, help you understand your emotions?

JD: Absolutely. I think I could be better at being a prolific songwriter, like honing my discipline by writing everyday. My history has definitely been: take a step away for a month or two months, and then when I’m feeling something there’s no stopping me from writing—it comes out, and that’s how I process my emotions. “Eyes Are Red, Don’t Be Ashamed,” was one of those songs where I couldn’t stop it. I also was wanting to pull the tracks out from under misogyny, sexual predators, all these systems that are still in place that allow those issues to thrive, and for women to not be believed.

AF: I know you’ve been volunteering at Aurora Commons, a community space for unhoused folks in the North Seattle area. How has your time there influenced your music?

JD: That came into the song “Switchblade.” And, I would say, into the more general narrative of the record, which was just like, no longer letting myself be as veiled as I think I have been in the past lyrically. Sometimes, you want to say the true thing instead of making it poetic. And, I learned that deeper vulnerability volunteering at the Commons.

AF: Are there any instances that come up for you when you think about your time there?

JD: Just personal stories – the things these women would share with me, trauma. The one consistent thing, hands down, with so many of these women is that there’s some kind of abuse in their childhood – sexual, violence or whatever, something traumatic has happened. It’s crazy to hear that kind of brutal honesty from them, and also at the same time be hearing in real time, “Hey, these are my needs,” because there’s no room to hide them because they’re living from minute to minute on the street. That showed me, even though I don’t have the same stories as they do and what they’ve gone through is a lot darker than what I’ve gone through in my life, it’s about compassion. I don’t even have the stomach anymore for hiding behind walls, mincing my words—this is what I’m going through and this is how I want to be here for people.

AF: That really comes across and the listener can connect to that right away. Also, I hear a sort of haunting, bittersweet element, mingling with that increased decisiveness. I read that you recently reconnected with your birth mother and I’m wondering how that altered your perspective on identity and making music?

JD: I think everyone can relate to the feeling of wanting to know where they belong, and even when you know those things it can still be tricky to be confident in who you are. I’ve always been searching for that big question, where do I belong? Sometimes it’s a question, hearkening back to what you were saying earlier about like women in the industry, like—where do I belong in this industry? How do I find my place and keep my voice and my independence, but also connect with other artists, other women, and be part of a community, not just an island?

When I met my birth mom, it answered a lot of curiosities that I had, like where did I come from, what’s the story? What did I look like? I had never seen a baby photo. I knew I was half Mexican and that’s it. And I knew her name. And then recently I found out—I don’t know who my birth dad is—but at least through 23andMe I found out, I was like holy shit, I’m half Jewish. I found out in the Taco Bell drive through. Many things have happened in the Taco Bell drive through for me.

AF: I know you co-produced this record. What do you enjoy the most about the production process?

JD: Oh man, everything. It really is one of those times where I shine because I don’t overthink things, I’m just able to go, go, go. Whereas, I tend to overthink in the songwriting process. Like, if it doesn’t happen quickly I might kill a song because I overthink it and don’t finish it. But when a song is done, I call it done and that’s it, and it’s time to figure out what world that song needs to live in. With production, it always excites me to ask, what world am I going to create for this song? What world am I going to create for this record? Where does this need to live? I often go to different worlds from day to day in my head, and I need to go to those places to be creative. It’s not even a choice, I just go there. So it’s amazing that you can go any which way but you have to choose something, and then point all the arrows in that direction and go for it. That’s exciting for me.

AF: Did you teach yourself with trial and error or go to school for it?

JD: No, it’s honestly such a sandwiching of having been in so many different studio recording situations over the years now. Learning what I like, engineering style, learning the vocabulary for things, when you hear something in your head and you don’t know how to communicate that, you have to get better at that, so that’s a skill that’s been sharpened. I am obsessed with mixing, different frequencies, all these things that are a part of my creative DNA and makeup, but those things have all been sharpened over the years as I’ve been in different situations.

AF: One of your “impossible weights,” to use your term, is that you’ve had mental health struggles and depression. What’s your perspective on mental illness and the creative process? Is it a necessary part of your art-making or do you reject that notion?

JD: I don’t think it’s a necessary part, but it informs the process. I think you could be totally healthy with your mental state and still create beautiful art, and you can be unhealthy and still create beautiful art. There are different tools that you can use, like if you choose to lean into the unhealthy. For me, there are tools I had to gather. You can’t totally eliminate anxiety out of your life. It’d be nice, but I definitely think that some stuff fuels a fire if you allow it, at least for me.

Sometimes, we glorify [the idea that] your art is only good if you’re feeling bad and I don’t think that’s true. There is beauty that can come from the ashes and the dirt, but if you lean on it, it can be a pretty unhealthy place. There are consequences, internally and relationally.

AF: This has been a really hard year. What do you hope this album contributes to the listener’s experience and recollection of 2020?

JD: When I first set out to make this record was when life was colorless and I was in a bad place and it’s just like, you know what, I want this record to be resplendent. That was word that came to me – full of life, full of color. And the color of it to me is predominantly green. That to me, is an association to being alive. That’s what people need right now. Whether it’s doom scrolling or all this terrible news that is happening, we lose sight that there can be joy and hope and color—it’s getting swallowed up by the bad. It’s okay to feel life and make space for things that are life-giving, even in the midst of tumultuous times. So I hope this record can be a breath of fresh air for people, and allow them to feel what they need to feel.

Follow Deep Sea Diver on Facebook for ongoing updates.