I’m getting a lot of funny looks on the train these days. It might be because protruding from the sleeves of my tiny motorcycle jacket are two hands, holding a book. A book with Céline Dion on the cover. Perhaps my fellow commuters are confused as to why a young, angry looking woman is reading an actual piece of literature about the Quebec chanteuse everybody loves to hate.

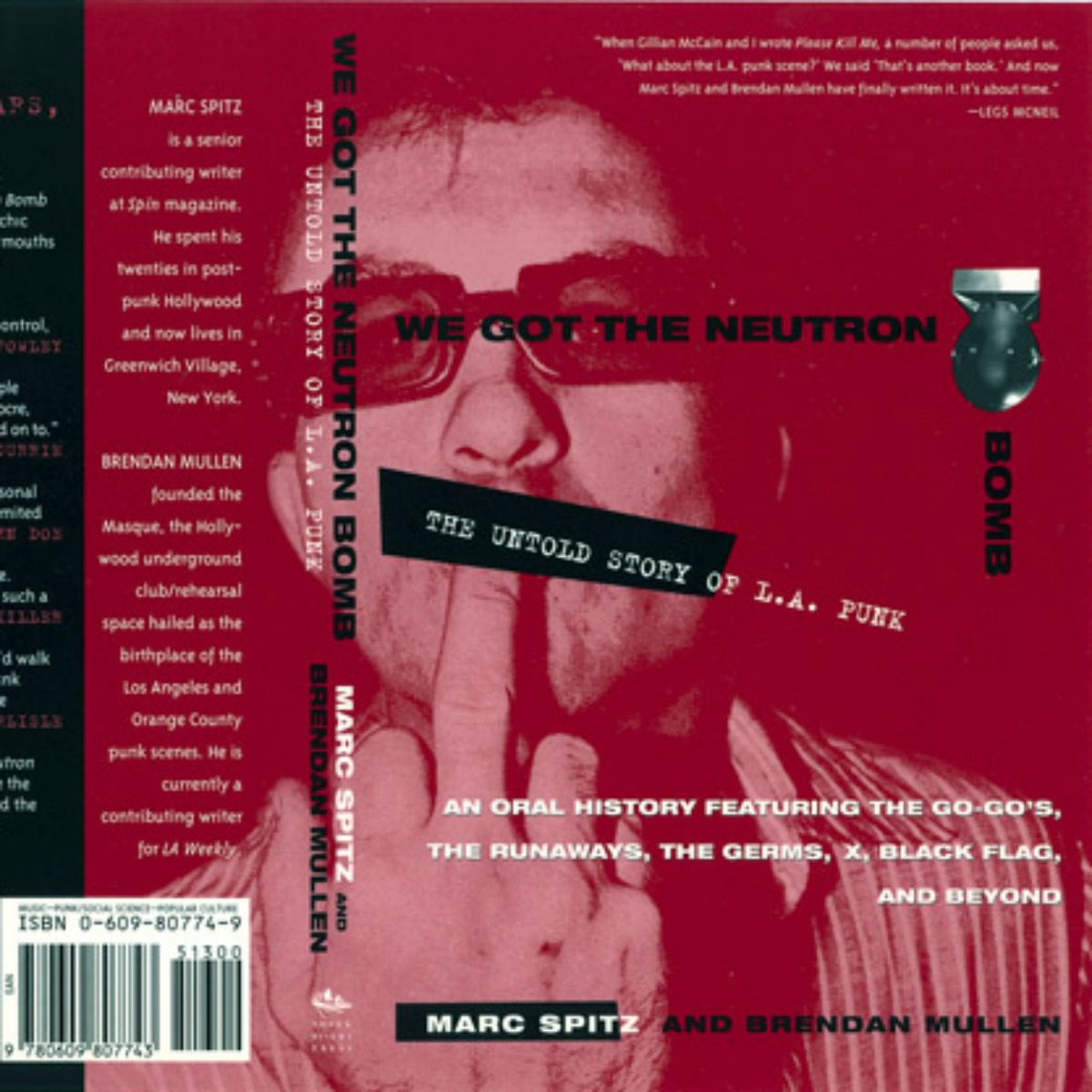

The paperback in question is Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste by critic extraordinaire Carl Wilson. It is part of the acclaimed 33 1/3 series, in which musicians, journalists and the like write a smallish book about one specific album, in whatever style they desire. While so many of these books have been penned about canonized works – Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, David Bowie’s Low, etc. – Carl Wilson chose to invert the model by writing about something he…hated. But here you won’t find reckless diatribe. Instead of mindlessly spouting insults, Wilson steps back and asks: ‘why do I hate Céline Dion?’ What evidence can support the squirming reaction upon hearing her voice when she is literally loved by millions?

For music makers, critics, and enthusiasts, there is often an invisible and ever-changing list of what is cool to love. But there is a sister list for the opposite – what’s cool to hate. It sounds juvenile but one of the things I’m learning from Wilson’s book is that much of what makes up taste politics is just as juvenile as a high school cafeteria.

The book goes into far denser socioeconomic arguments for the origins of taste – which I won’t attempt to replicate as it’d be a tall order to do Wilson’s writing justice. But one thing I will recycle is this question: why do I hate ____________? And furthermore, what’s it like to be allergic not to schmaltzy pop that all of your friends hate along with you, but something everyone you know adores?

Ok. Here goes. Get the wood for my crucifixion. Tell my family I love them. If Carl Wilson had an advice column tending to the ambivalence of blind dislike – dislike you can’t always explain, I would write to him:

Dear Carl,

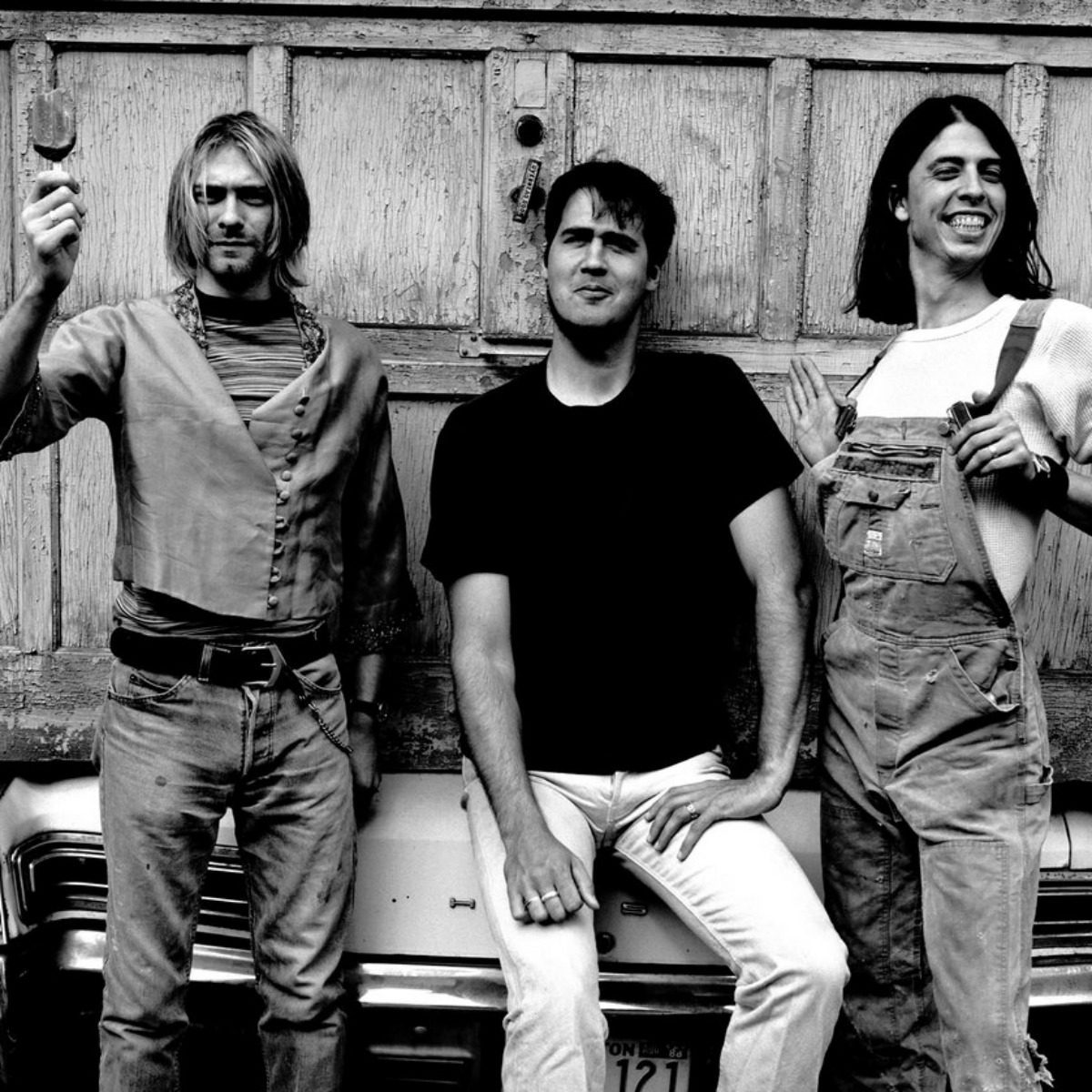

Why do I hate Nirvana?

-The Guilty Washingtonian.

One thing Wilson and I have in common is not only that we strongly dislike a commercially successful, wildly popular artist, but also that we both hail from their place of origin: Wilson from Quebec, and I from Washington State. I don’t doubt that this affects the perception of said recording artists. When inundated with something for years on end, you have one of two options – embrace it or run for cover. There is rarely an in between, especially for the likes of Dion and Nirvana, both extremes on opposite sides of the musical spectrum. Does anyone ever say, “Oh, yeah, Céline Dion, she’s alright. I won’t put it on, but I won’t turn it off either?” No. Likely this could be said for Nirvana as well, a band whose zenith was a worldwide phenomenon, but also a local victory for the Pacific North West. And that last factor makes me feel like an enemy on home turf. The visiting team…but hey, I’m from here!

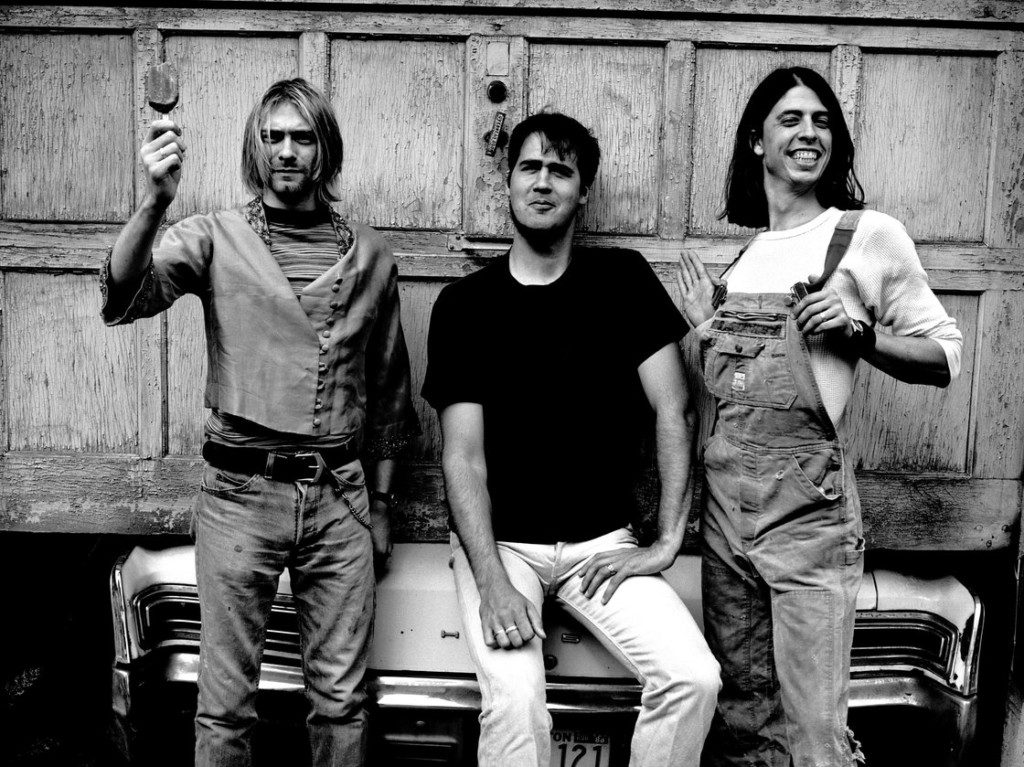

I’ve tried to like Nirvana, believe me. I assumed I would. I don’t even remember how I heard of them, and this is coming from someone whose weekly column is practically a temple to remembering the exact moment you first hear a band. I just remember…knowing. Like their names and story and that album cover had been taught to me in daycare before I could form cognitive boxes to put things in. Nirvana was in the water growing up. It still amazes me that Seattle hasn’t erected some statue of Kurt Cobain right next to the one of Jimi Hendrix on Capitol Hill.

When did my knowledge of Nirvana go from intrinsic local legend to awareness of their sound? Likely it was when a combination of curiosity, perceived coolness associated with the wearers of their t-shirts, and the CD subscription club collided. Remember that staple of music consumption in the 90s and 00s? Those chintzy catalogs filled with mostly awful but some classic albums. The promise of “10 CDs FOR 99 CENTS!!!” (And then canceling immediately upon receiving those 10 picks).

So it was through a CD club that I first acquired – of course – Nevermind. I could finally investigate what all the fuss was about. I slipped the disk in. I slipped into that cerulean pool with that money hungry baby. And I felt nothing. Not just nothing, but unmoved. Even agitated, which I guess is something. But it wasn’t an invigorating agitation that some music inspires, just a rash. I couldn’t stand it. You can imagine the kind of confusion this might stoke in a 12-year-old eager to embrace the musical heritage of her region.

Disliking a deeply loved and influential band can’t be so bad, right? These days it’s common parlance to not be that into The Beatles, citing more obscure products of the 1960s instead. But this is not the case with Nirvana, at least not in my experience. I wonder if it’s because the people that grew up with them, that remember and lived in their heyday are now the tastemakers. I’m not sure. What I do know is I’ve never been met with so much adversity when discussing musical taste as when I say that I don’t like this band. It cuts people directly to the quick.

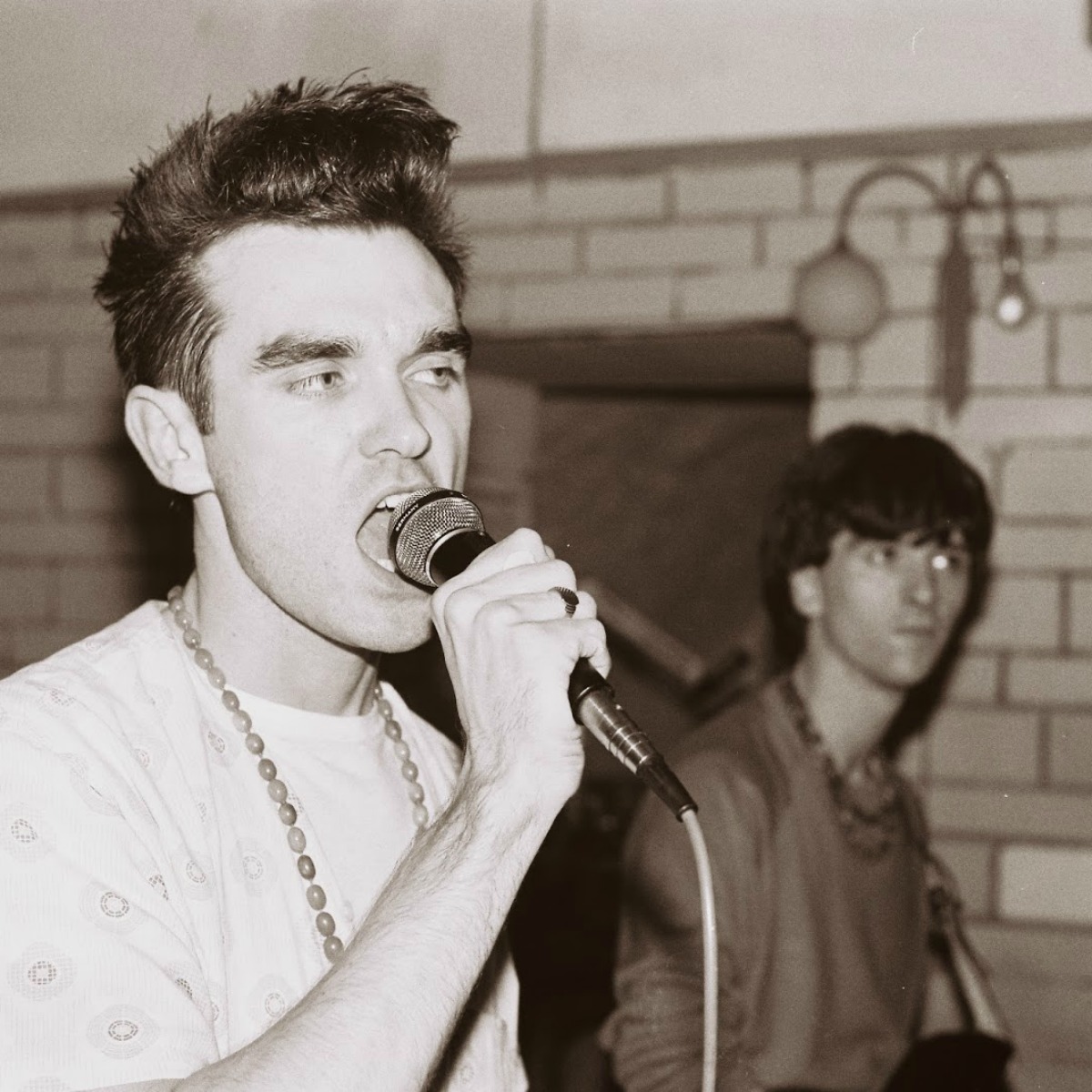

The opinion is seemingly so offensive to Nirvana fans that they attempt to find a manifesto as to why I feel this way. They insist that that my taste is not genuine, and rather born of some pathetic desire to be “cool” or “different.” But I gave up those hopes and dreams when I started listening to The Smiths like everyone else after years of steady resistance. It’s also not the common accusation of regional rebellion, allegedly serving the same purpose of setting myself apart from the masses. The fact of the matter is, disliking Nirvana does absolutely nothing for – as Wilson and Pierre Bourdieu. would say – increasing my “cultural capital.” If anything, it is a detriment to my social interactions when it comes up. I would love nothing more than to stop constantly pissing people off by answering a question honestly. What is that like? Tell me, because I will never know.

One of the things I strive to do as a music writer is really analyze why I’m reacting a certain way to something. Is it because of a sound, or a symbol? Because I was told to, or a genuine sentiment? Often I will listen to bands I can’t stand repeatedly, just to make sure I know where I’m at. I once cycled through all of my mom’s Genesis records just to make sure I wasn’t missing something – that I was an educated Genesis hater at the very least. It reminds me of taste buds: how with age they gradually change (well, die) and often people’s food preferences become less rigid over time. For this reason, I make an annual effort to give my most loathed food, the banana, another try. And though it becomes a teensy bit easier year by year, it still makes me gag every time.

So here I sit, listening to all three Nirvana LPs as an attack on my own ego, hoping that I will eventually enjoy them. But they are still mushy bananas to me. My inability to convince people of my honest opinion has been met with such opposition that once an ex-boyfriend casually put on Bleach to see if I would joyfully ask, “ooh! Who is this?!” But it bristled against me like steel wool, and I of course, knew who it was.

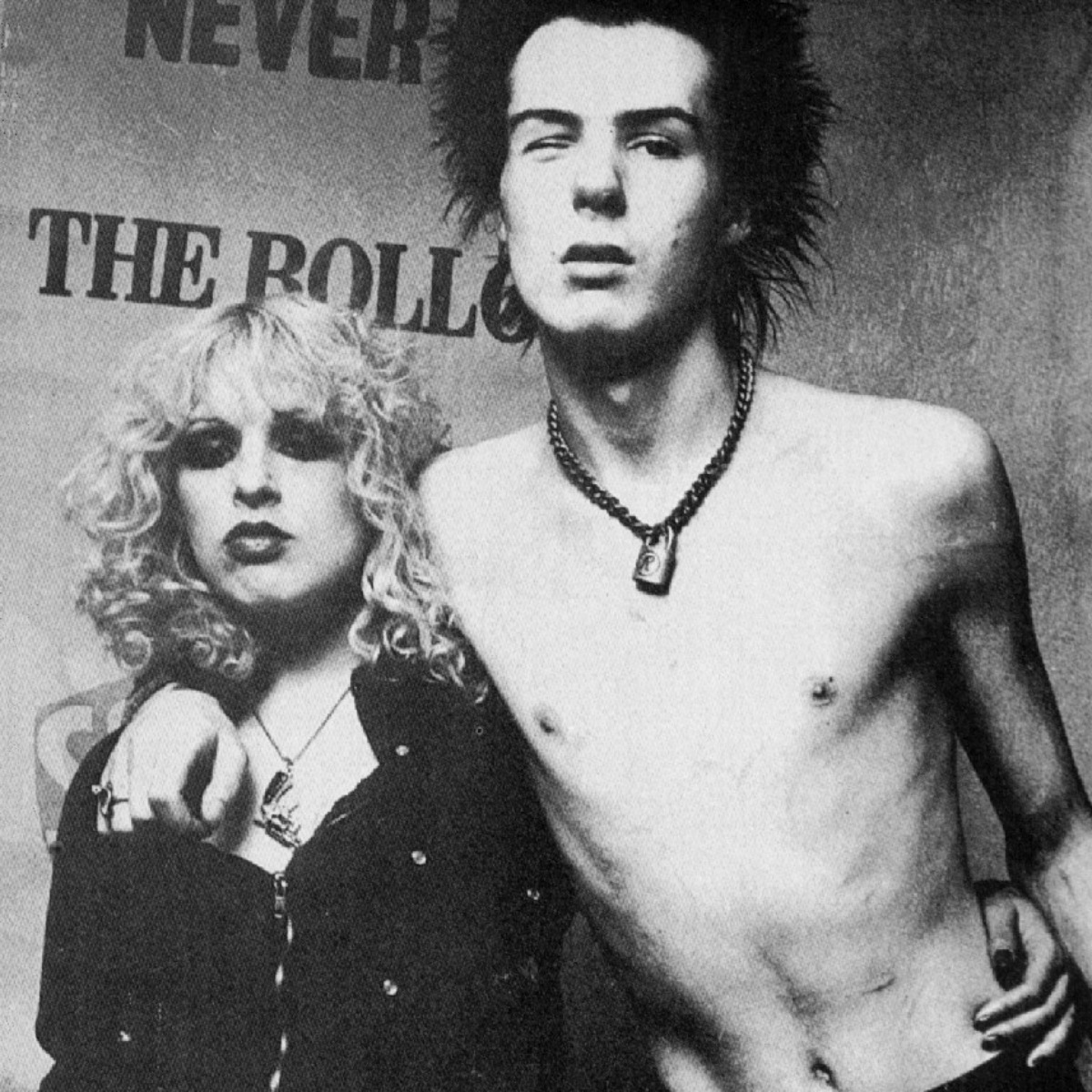

To make matters worse for my Nirvana-obsessed friends: I love Hole. That’s like saying you can’t stand John Lennon but you really dig Yoko Ono records, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not something people like to hear…especially when there is a whole camp of conspiracy theorists who think Courtney Love killed Kurt. It’s like ripping open a scab and packing it with fine salt. But my love of Hole has taught me something about my aversion to Nirvana…that maybe my relationship with the band isn’t so complicated and mysterious after all. I’ve never said Nirvana were a bad band, or bad songwriters. I can appreciate and admit that quite the opposite is true. So if the songs are good, what is it?

It’s just that voice.

Kurt Cobain’s voice alone is what makes my skin crawl. I hate it. And it’s not like I listen exclusively to Chris Isaak and Cher. I completely dig on fucked up, pitchy, gravelly, “bad” singers. Just not this one. I’ll probably never be able to explain exactly why.

I find it hilarious that it has taken me so many years to arrive at such a simple, even boring resolution. No one can really debate vocal preference, right? Every once in a while, it’s kind of nice when a convoluted question can be reduced to a crude, shallow answer. I just don’t like the way it sounds. I just don’t like the way it tastes.

Void of philosophy or agenda I can say: I just don’t like bananas. For now.

(Maybe I kinda dig this, just a little:)