ONLY NOISE: Personal Record

I no longer own my very first record. It was AFI’s Very Proud of Ya, (that’s pre-emo AFI for those of you wondering), and I bought it in Seattle with my own allowance. I can still hear it spinning on the portable turntable my dad leant me for late night bedroom listening. The portable record player was a goofy little invention. It was called a Discman, which is hilarious in retrospect considering its makers couldn’t have predicted the imminent reign of CDs and their portable players. The Discman was essentially useless – the LP’s edges protruded from its sides, there was no real way to carry it around, and of course the moment you played a record in transit, it would skip violently.

Therein lies the paradox of the “portable record player,” but it worked perfectly for my pre-bed indulgences. Every night for months I would load up the Discman with Very Proud of Ya (it was the only record I owned for a while), slip on a pair of padded headphones, and gingerly lie on the brown carpet, my head inches from the swirling black polyvinyl. I was tethered to the music physically, but if I closed my eyes, I was transported miles and decades from post-millennium rural Washington.

Listening to Very Proud of Ya now, I recognize it is not a very good album – and yet some odd memories strike me – the first of which being the above scene, in high definition. The smell of the carpet, the temperature of my middle school bedroom…the nightly ritual I haven’t thought about in so many years, despite how much joy it brought me. I remember specific parts in each song – riffs, drum rolls, and Davey Havok’s snarling delivery.

I notice that all of my favorite parts as a 12 year old are the same today. And though I don’t find it to be an exceptional record as I listen with 27-year-old ears, I do miss it. I wish I still had it. It is, for some reason, particularly upsetting that I no longer possess the first record I ever bought. Its absence feels like losing all of the love letters from your first boyfriend. You weren’t clinging to those! They were emotional artifacts!

Ok, I’m an emotional hoarder – so what?

I can’t remember exactly why I got rid of Very Proud of Ya, but I can take a pretty educated stab at what happened. I reckon that one of my very few friends enlightened me to the fact that in more recent years, Davey Havok and AFI had gone the goth/emo route – so I wanted to absolve myself of any association with the band whatsoever. I then sold the LP back to the very Seattle record shop from whence it came, and bought an original pressing of The Incredible Shrinking Dickies on store credit. Is The Incredible Shrinking Dickies a better record? Yes. Does it flood me with tingly memories of my 12-year-old self? Sadly, no.

Since abandoning my very first LP, I am a bit more careful about the records I let go of these days; though arguably, too careful. The level of sentimentality devoted to my record collection can be summed up by that brilliant line of dialogue in the 2000 film adaptation of Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity, when Rob (played by John Cusack) is rearranging his albums autobiographically. “If I want to find the song ‘Landslide’ by Fleetwood Mac, I have to remember that I bought it for someone in the fall of 1983 pile, but didn’t give it to them for personal reasons.”

While I have no patience for filing my records with any system of organization, their origin stories can be recalled with the same amount of detail as those in Rob’s collection. For instance, I couldn’t possibly get rid of the crap albums from any of my musician ex-boyfriends; it would do them a service to put their music out in the world. Better to let them sit inert on the shelf, instead. I realize that I don’t rationally need two copies of Keith Jarrett’s Concerts LP, but one I bought off of a nice street vendor in a strike of serendipity, and the other was a gift from that cute record shop boy I used to date. Plus, one is a boxed set!

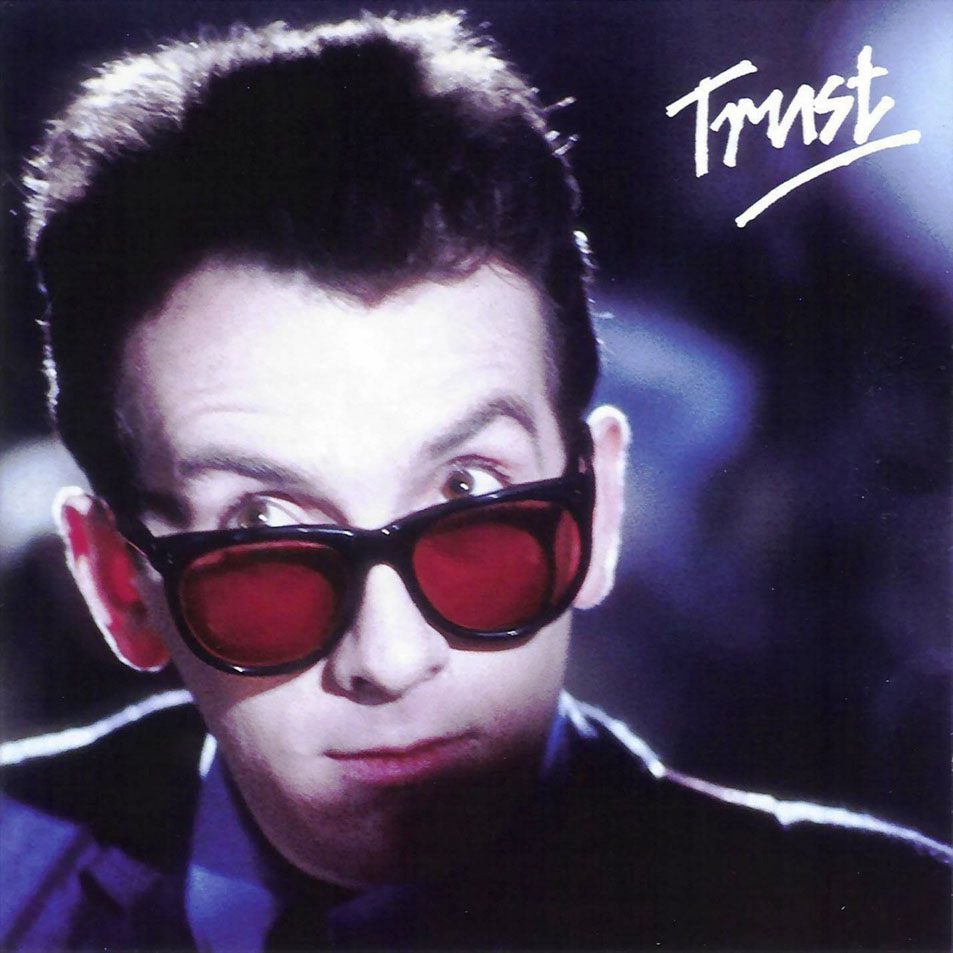

The same emotional “reasoning” applies when it comes to my promo copy of Elvis Costello’s 1977 debut My Aim Is True. I wouldn’t dare swap it for a different pressing, as that would rewrite the terrible history of how I acquired the album in the first place.

It was May of 2005 – May 21st to be exact, the fifteenth birthday of my adolescent best friend, Daniel. Daniel was one of the few people in school who shared my obsession with music. We (very) briefly played in bands together, but spent most of our free time lying in his dark bedroom, listening to entire records in silence. On heavy rotation were albums like Modest Mouse’s Good News For People Who Love Bad News, Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Fever To Tell, and anything siphoned from a Quentin Tarantino soundtrack. I showed him the raw pop power of Richard Hell and The Voidoids, and he singlehandedly introduced me to The Pixies with a burned copy of Doolittle.

Naturally, Daniel wanted to spend his birthday in Seattle. We were of the few cultured people in our high school, you see, and sought the finer things in life… like the Häagen-Dazs ice cream shop at 4301 University Way. But we also sought record stores – places that didn’t exist in our hometown. And so, Daniel, his dad, and I spent the day gallivanting around Seattle’s University District, digging through bins. It was within these bins that I found it: an original pressing of My Aim Is True – used, but in fine condition, and priced at a fair $4.99.

Within milliseconds of me raising the LP from its vinyl neighbors, Daniel’s hawkeye spotted it three sections away. “Can I get that?!” he asked, beaming. We had both commenced our Elvis Costello phase within the past year, so this discovery was like striking gold. Hmmmmmmmm. This would take some judicious thinking. On any other occasion, a staunch finders-keepers law would apply – but this was his birthday after all. I decided to be kind, to do what any loving, considerate friend would do…

Oh, no. No I did not. I laid down the finders-keepers law hard and mercilessly. “But, it’s my birthday!” he pleaded. With the stony resolve of a miserable 15 year old, I stood my ground, and kept the record for myself. I have never felt more selfish. This memory stings me, makes me cringe every time I hold that album in my hands. I’ve considered shipping it to him, but it would probably be too little, too late. Besides, the record has become a symbol; it’s a painful but necessary reminder to be less of an asshole. And that’s certainly something worth holding onto.