ONLY NOISE: How PUP – and Punk Rock – Changed My Relationship with Physical Intimacy

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Sophia Vaccaro finds empowerment and personal autonomy in the mosh pit, with PUP providing the punk rock release. The mosh pit at a PUP show helped Sophia Vaccaro see the punk tradition as an exchange of energy rather than a violation of space.

“The mosh pit never lies,” Norah reminds herself in Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist. It took me a room full of friendly punk kids and almost ten years to understand what she meant.

I was not a wild teen. I was not even a wild college kid. Nick and Norah’s world of all-nighters, secret shows, and closet makeouts was as astronomically foreign to me as it was eminently desirable. I wanted to traipse through the post-midnight music crowd mooning over someone while not realizing how absolutely fucking cool I was being, too! But why was it so fucking hard?

It was the pit; moshing was asking too much of me. I spent a long time — too long — hyper-aware of the bodies of men in my space. I can’t stand a casual touch from a man I do not know. It feels like a physical weight, like leeches peppering soft marks on my skin to remind me: you did not want this hug. You did not want this hand on your shoulder. You didn’t want. You didn’t want. Everything was always about what I didn’t want, and it was exhausting.

So how could someone, uncomfortable even with the physical feeling that comes from an uninvited look, willingly throw herself into a horde of sweaty, aggressive punksters? Enter PUP the band — and my friend’s pink backpack.

I love PUP. Formed in Toronto in 2010, PUP consists of bassist Nestor Chumak, vocalist Stefan Babcock, drummer Zack Mykula, and guitarist Steve Sladkowski. Since their first self-titled LP, they have been steadily evolving as musicians and lyricists. But it’s not only the music that’s fucking good; they also seem to be four actual friends who are doing their best to deal with mental health, growing up, and the complexities of the occasionally vagrant musician life. They are more than aware of the community that has grown around them; in anticipation of their third full-length album, Morbid Stuff, which was released last Friday, they asked fans to cover the second single, “Free at Last,” with only the chords and lyrics available. The result was a funny, light-hearted music video compiling these clips that was not only surprising in its musical diversity, but also surprisingly tender and utterly appreciative — of both fans and band alike.

Release is paramount to every PUP song, as it is paramount to punk. Every song is an expungement of all the bad things you were thinking and feeling and have convinced yourself you were floating on top of which you were in fact slowly sinking under. There are many things about this that could be considered unsettlingly hypermasculine and phallic, especially when experienced live — the half-swallowing of the mic, the aggressive guitars, the plain and simple anger of it all. But I believe that this idea of release in punk is fundamentally about the body. Movement in connection with music is a way to take your love for the sound, unwind it from the ball inside your chest, and let it out. PUP showed me how that ball could have somewhere to go.

They were doing a show in Oakland as part of their headline tour for their second LP, 2016’s The Dream Is Over. I wanted to go. I needed to go. They were all I had been listening to for weeks straight at the time. But the part of me that stands between myself and the world, pickax in hand, had some considering to do. What would the crowd be like? What would the vibe be like? And, most importantly: would there be somewhere for me to hide?

The music won, because the music always does.

I bought my tickets, employing my friend Maranda as my chaperone. We Ubered to Starline Social Club, and as we waited outside the entry steps on that cool September night, I prepared to face the masses — and the men — from the fringes of the audience.

Only that is not what happened.

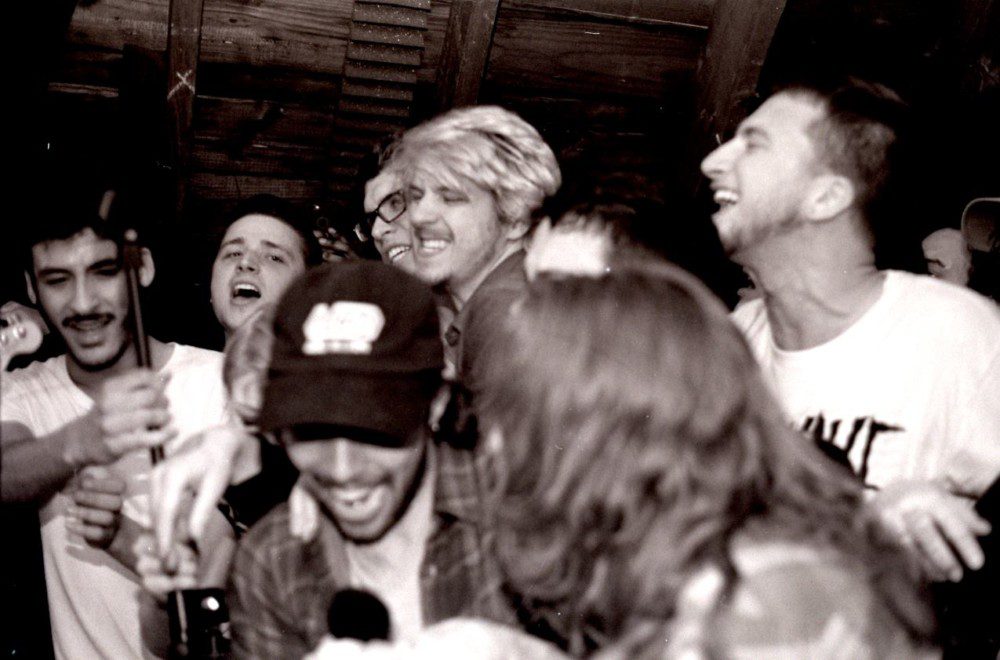

Not even halfway through the show, I was sandwiched between two huge guys, watching them good-naturedly shove anyone spinning out of the mosh pit back into its boisterous center. I watched, and I learned. As I screamed along to “Doubts” and “Guilt Trip,” I let my body relax into flow of the others around me. I began to see them not as violations of my space, but rather as an extension of myself and how the music made me feel. The last piece of the puzzle was watching Maranda, a modern dancer who is in incredible control of her body, throw herself with single-minded joy into the center of the pit, her mini pink backpack the only part of her I could see as she tossed and was tossed.

That’s the key, I realized. The mosh pit is not a stripping of power for the benefit of the biggest and strongest — it is an exchange. It is a release that gets passed from body to body, and if it is too much for one person to take, there are people waiting to pick you up, even you out, and send you back in. I didn’t go into the center of the pit that night, but I felt something loosen inside me. Those ragged and dirty knots of distrust had been tied by fear, but the music and mayhem of punk rock — and PUP — had started to pick them free.

As I said: I was not a wild teen. In fact, I would say the peak of my Big Messy Adolescence is currently happening right now, after a year full of last-minute moves, big betrayals, old friends lost and older friends renewed. So to make it through 24, to do things I had waited long too do, I needed to find a place where physical intimacy with people I did not know was not a cue to panic; I needed to have space inside me for things that were not fear.

Today, I turn 25, and Morbid Stuff arrives just in time to help me reckon with the good and the bad of those experiences. Besides mental health and yes, morbidity, the new LP is more than anything a painful dive into the hell of caring about people who couldn’t be more indifferent towards you. It is a testament to the self-inflicted, full-body bruise of obsession that blooms as you grasp for information and explanation, while those people think about anything else but you. The city of Toronto acts as both peer and antagonist, veering from rapscallion comrade-in-arms in “Morbid Stuff” to looming oppressor on “City.” The fact that it remains unnamed on the latter parallels the theatrical storytelling of 2016’s “Pine Point” and “The Coast” and this album’s “Scorpion Hill.” As Babcock croons “don’t wanna love you anymore” on “City” it’s not clear who this is in reference to — a partner or the city itself. It’s a pertinent reminder that, in your 20s, the familiar becomes frightening, and your life can seem a folktale rife with monsters that take the faces of the people you care about — or yourself. And while these bigger-scale moments still hit, it’s the smaller stuff — Babcock’s cold-sweat fear about the potential deaths of former partners; running into one of those previously mentioned indifferent people while in the midst of mundanity at the grocery store — that have me inching further and further into the pit.

The first time I heard “Closure” on the new LP I yelped “fuck!” loud enough for a bleached-tip pedestrian at Yerba Buena gardens to look at me in semi-alarm. This was justified, as it was semi-alarm that was ricocheting through my body — at how hard this song was hitting, already, thirty seconds in. At how excited I was, changing my socks on a granite pillar for the benefit of my not-yet-broken-in Doc Martens, to press out my sorrow into the pit and watch it be washed away and returned as something softer.

The second time I listed to Morbid Stuff, I found myself itching to move — it’s hard not to listen to PUP without wanting to thrash. I would have gotten up, walked straight out of my house and put on the blistering “See You at Your Funeral,” but it was pitch dark and 11pm, so I sat, bound to the steps above the kitchen heating grate.

I turned the music off. The first few listens of any beloved band’s new album are a sacred thing, and it wasn’t right.

But those initial run-throughs also illuminated to me how much my listening has changed. I can feel myself anticipating that release of movement, but I don’t imagine myself alone any longer.

That is why the music always wins. It will drag you closer and closer to the stage. It will make you want to feel the bodies of others moving around you, moving against you, pushing and pulling and jabbing and screaming, because not every touch has intent to take. In the mosh, which never lies, touch is trying, simply, to be.

I needed to be reminded that that I could do that.