ONLY NOISE: What I Learned From Bad Covers of “Hallelujah”

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Erin Lyndal Martin takes comfort in unexpected covers.

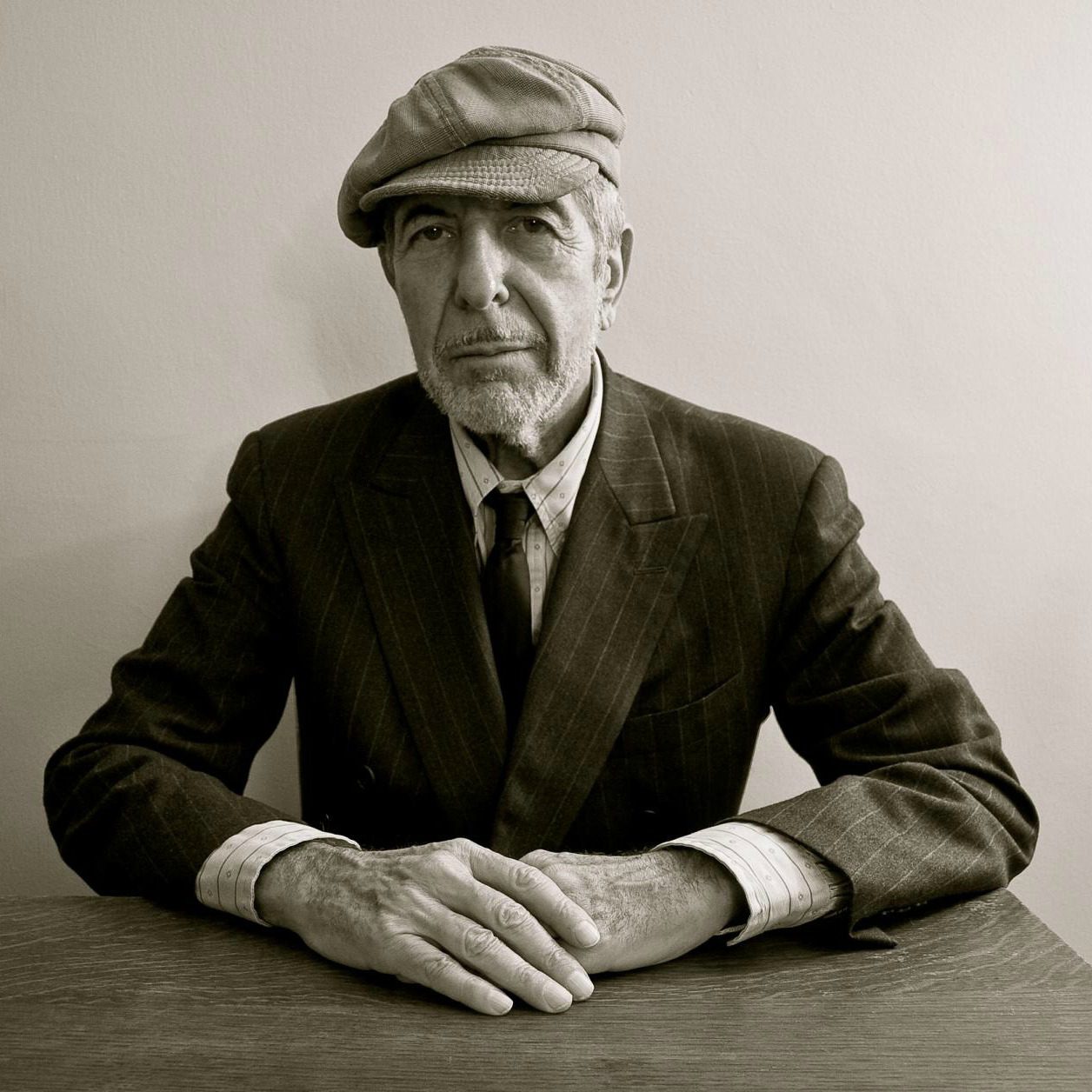

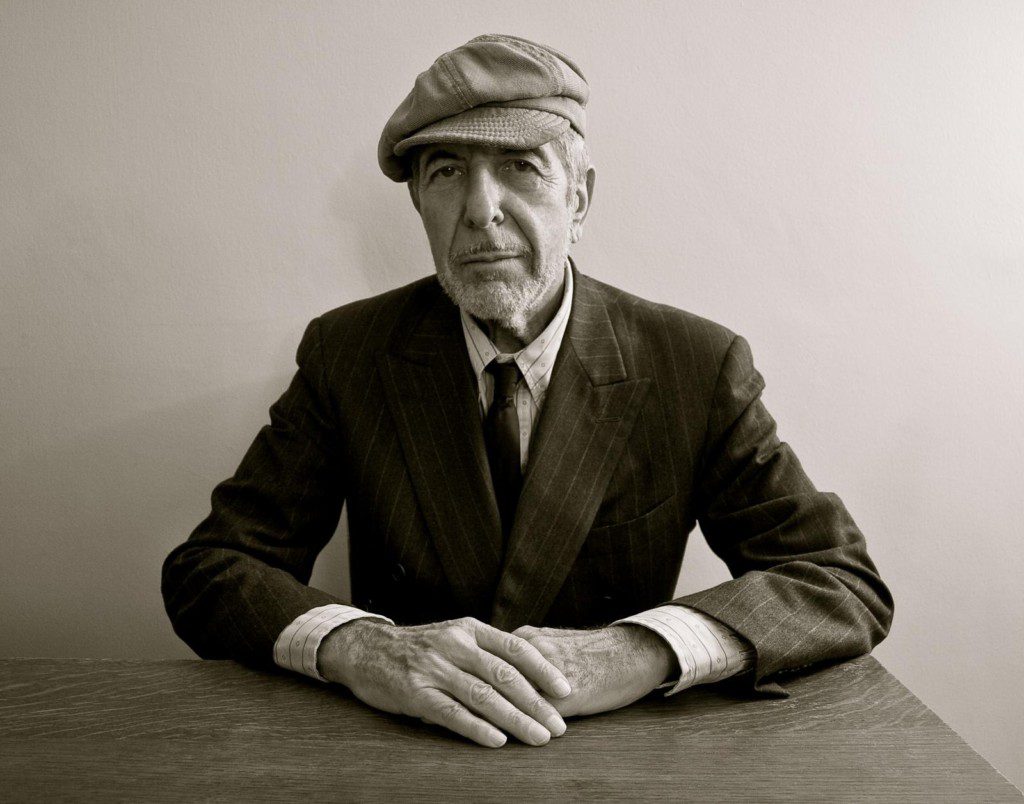

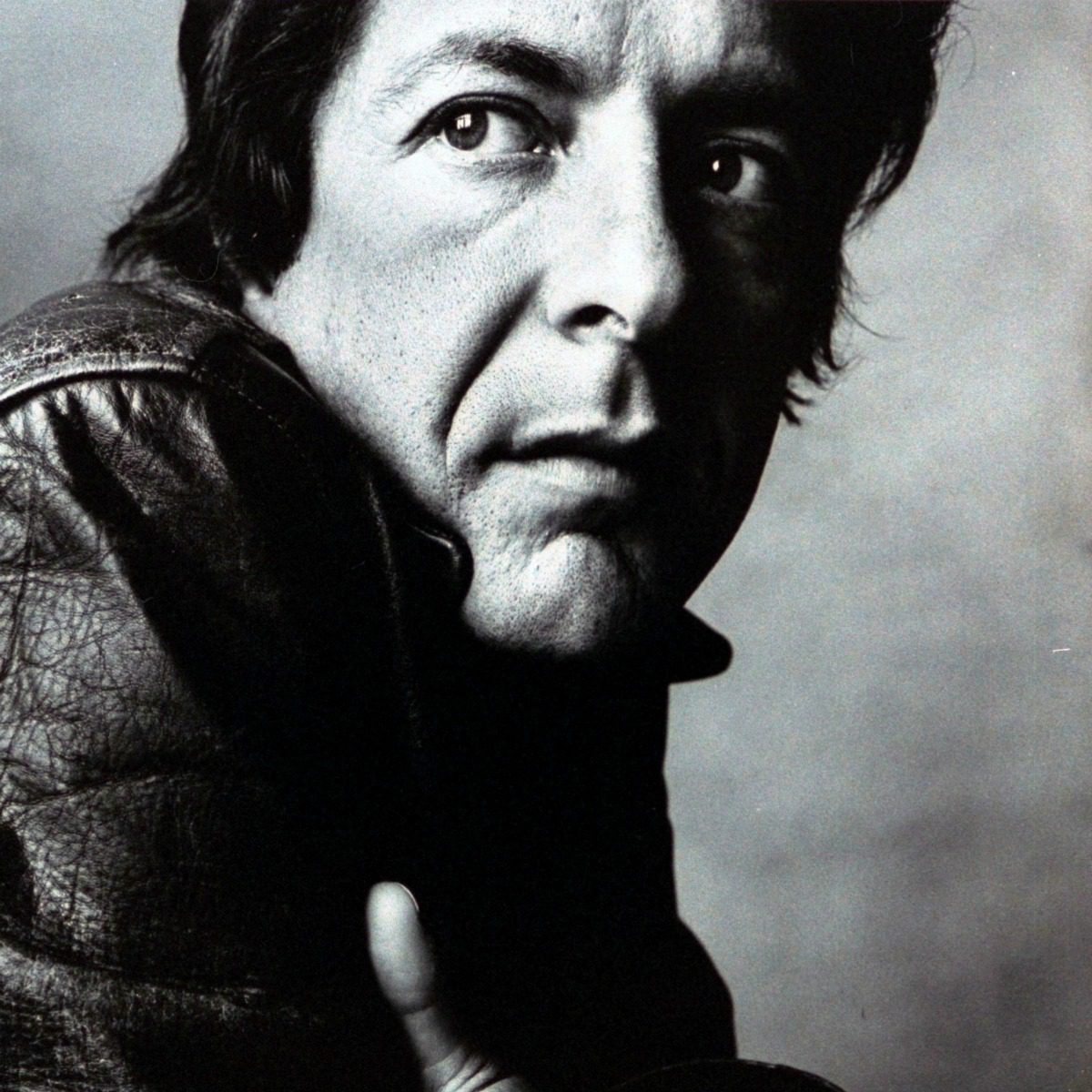

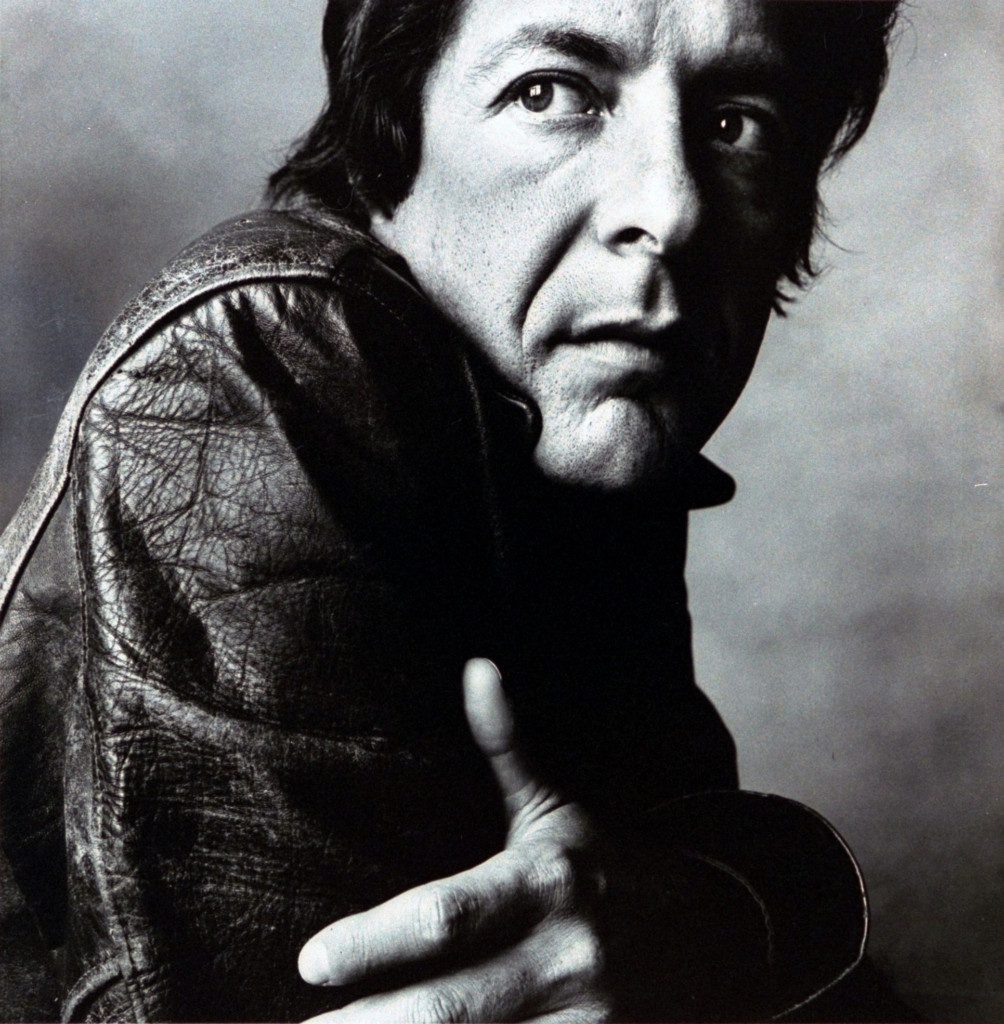

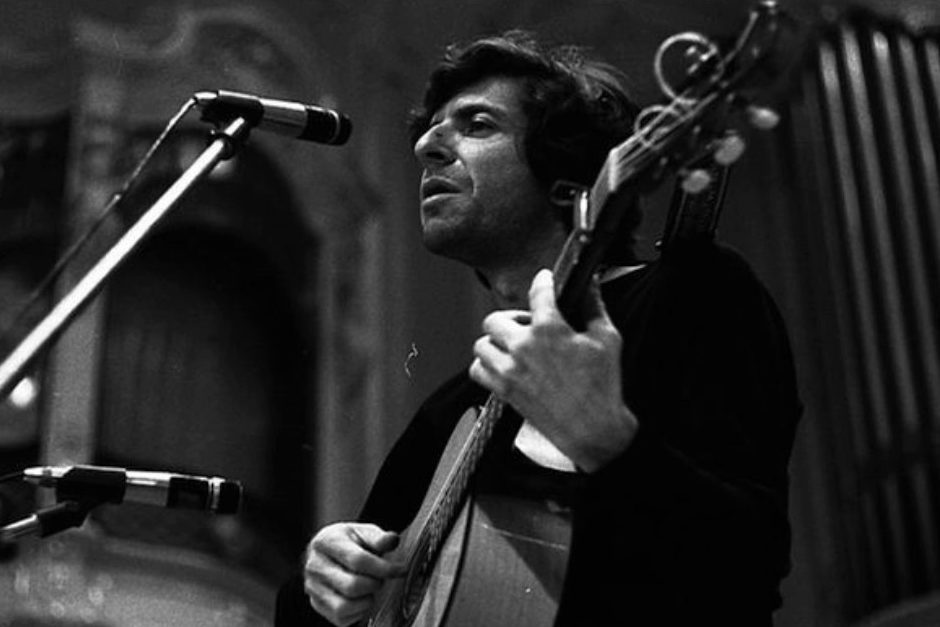

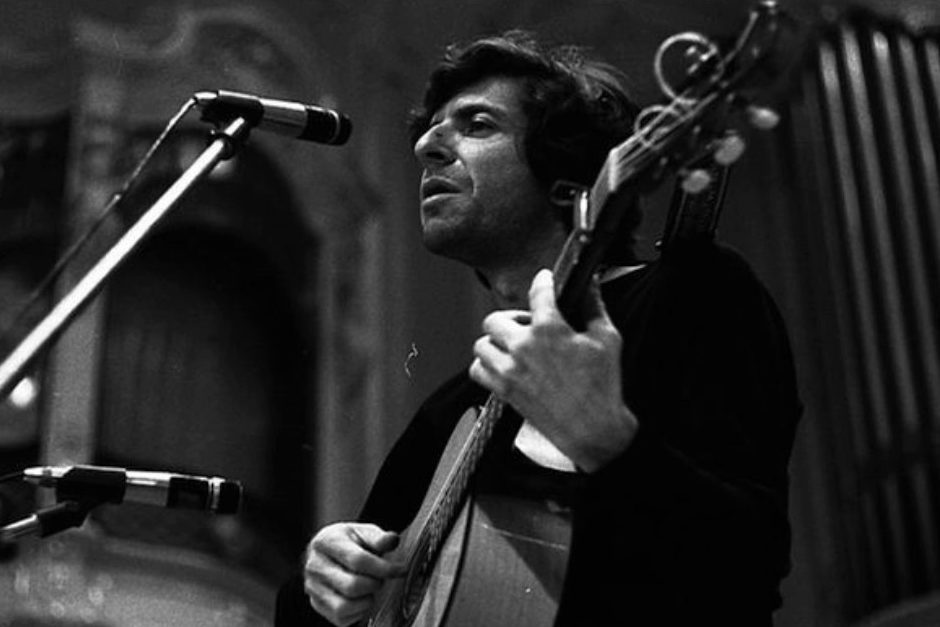

“Hallelujah” is pretty much a perfect song. Appearing on his 1984 LP Various Positions, it took Leonard Cohen so long to write that he kept a diary of his failures. The original song had 80 verses. The power of Cohen’s words doesn’t have to fade in the million bad covers, but the song’s over-use has made “Hallelujah” synonymous with artificially lending deep emotion. I often joke they’ll soon play it during Pat Sajak’s nightly final spin on Wheel of Fortune.

There are obvious outliers among “Hallelujah” covers, truly transcendent ones like Jeff Buckley’s, his elegiac falsetto highlighting the eroticism of the song. Or Kate McKinnon performing the song as Hillary Clinton after the 2016 election. But most covers lack the impact of these. While too many musicians to name have recorded the song or played it live, I have a special fascination with the more amateur covers.

Once I was browsing my local farmer’s market. It was 90 degrees, and the humidity lent a haze to the morning. A man was playing guitar and singing “Hallelujah” beneath the din of the crowd. For some reason it seemed odd to play “Hallelujah” in hot weather at all, in addition to the casual environs.

Maybe, though, someone there needed to hear it. Just as it was.

I realized this much later. Last year, I was waiting for my very late bus in a Greyhound Station. It was March 20. The anniversary of my father’s death. Things to know about my father: he loved Leonard Cohen, he loved trying to start philosophical conversations with strangers, and he wore sweatpants in public a lot.

He was, of course, on my mind there in the Greyhound Station. A few other people were there waiting, including a young woman listening to music on her phone, the volume in her earbuds turned way up. I didn’t pay attention to what she was listening to until she started singing along. Loudly. I could then tell she was listening to the Pentatonix version of “Hallelujah.” Hearing those lyrics on the anniversary of my father’s death felt magical and chilling.

I pictured my father there in his sweatpants. I have no doubt that he would have approached this woman and talked about the song. He probably would have sung along. And I think of some of the things my father said about Leonard Cohen, like that he “brings punctuation to experience,” and I thought he’d say that to this woman and not notice she had no idea what he was talking about.

I recorded her singing on my phone and sat excitedly in the station, uploading it for my mother and sister. My mother frequently looks for signs my father is reaching out, and I hoped she’d be excited about this. But she deemed it “too stupid to listen to.”

Eventually my bus showed up, and I went off on my trip. One night I ordered a Lyft to take me to a concert. The driver was… an eccentric fellow, who told me about this disgusting fruit punch flavored grain alcohol drink he liked to order by the case.

“Do you like music?” he asked. “I want to put on something relaxing.” He turned on satellite radio and a new age version of Sting’s “Fields of Gold” started playing. “This right here is what I like,” he said. “Pure classical jazz.”

When I told this story to a friend later, the only part he didn’t believe was that anyone would bother making a new age version of “Fields of Gold” since the original was most of the way there. It became a running joke between us, finding new age versions of that song or of other songs that are already soft. I even made a version of the original “Fields of Gold” slowed down seven times as a joke for him (as of now, it’s gotten 82 views).

Later, our friendship began to fracture. We’re not speaking now. I miss him. I miss looking for haunted items on eBay with him, and I miss his chocolate chip pancakes and goddammit, I miss joking about pure classical jazz.

In my therapist’s waiting room, a CD of new age versions of pop songs was playing, and there it was. A pure, classical, jazz rendition of “Hallelujah.” It was, of course, terrible, and there were all these bizarre keyboard flourishes that just didn’t belong, including this slightly jazzy outro that had nothing to do with the song.

Of course I imagined telling my friend. I’d say, “Well, maybe the outro was the only chance the musician ever got to experiment. Maybe it was his big moment, you know?”

And he would say something like, “There’s probably just an ‘artsy outro’ button on the keyboard.”

And we’d stay on the phone discussing what songs we wanted to hear lite piano versions of, and I’d swear that “What’s Up?” by 4 Non-Blondes would be ideal.

Then I remembered we wouldn’t have this conversation at all. Love is not a victory march; it’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah.

Maybe it’s all the lite piano I’ve listened to, but I’m starting to believe that sometimes “Hallelujah” finds us when we need it most, in the context when hearing it would do us the most good. Even if it’s a really, really bad version.

I still reserve the right to roll my eyes and make snarky remarks at when the song is performed badly or used inappropriately. Yet, two bad covers were there for me when I needed to remember what was eternal about my absent loved ones. “Hallelujah” is a capacious song, and it can hold even the Greyhound singers and the lite piano version, as well as ones like Jeff Buckley’s or Kate McKinnon’s that are universally moving.

Given Cohen’s humility, it’s very fitting that he subtly works his magic even through the unlikely troubadours we encounter in farmer’s markets and bus stations. As Cohen himself said, “The only moment that you can live here comfortably in these absolutely irreconcilable conflicts is in this moment when you embrace it all and you say, ‘Look, I don’t understand a fucking thing at all—Hallelujah!’”