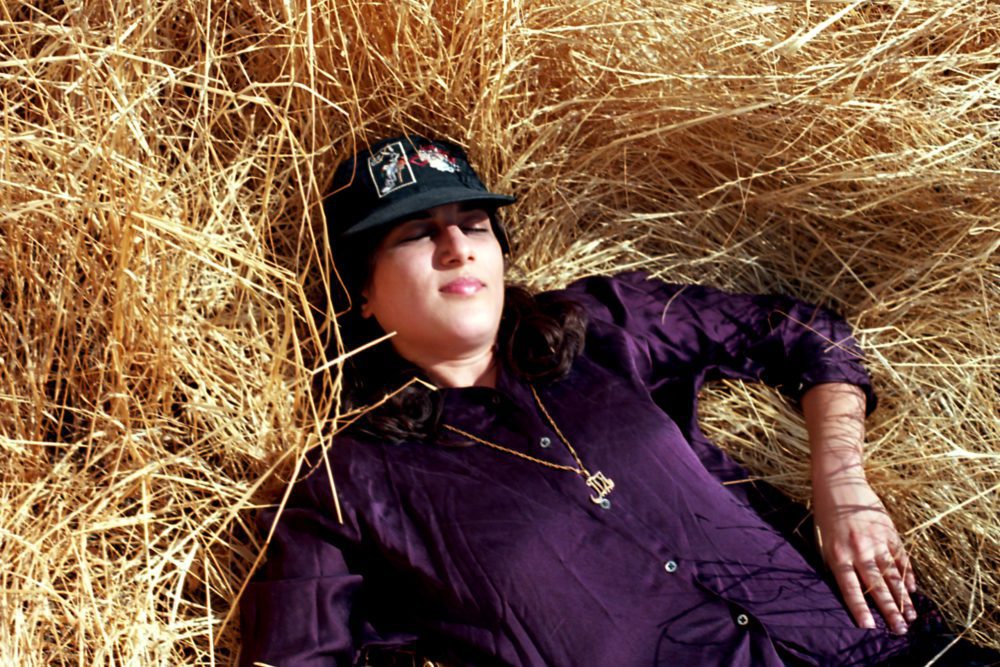

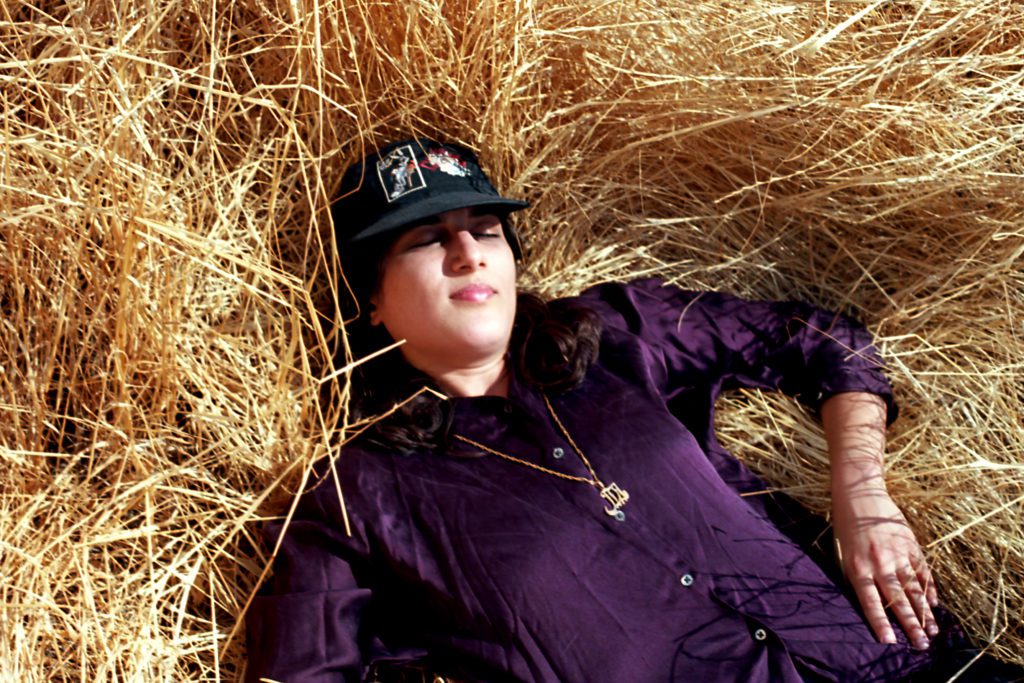

Maral Mahmoudi grew up with Iranian music. The DJ/producer, who uses just her first name professionally, was raised primarily in Virginia, near Washington D.C., but spent fifth and sixth grade, as well as childhood summers, in Iran. “I I have this deep history with hearing the music at all times, blasting on TV,” she says by phone from her home in Los Angeles.

Later on, she would develop her own relationship with the music. Maral dug through her parents’ collection of tapes – they’re fans of Persian classical music – and learned more about the philosophy behind it, the connection to Sufism and the role that improvisation plays in it. “Everyone learns the same repertoire of music, which is this ancient repertoire that’s been passed down orally for centuries. Then, it’s up to you to play it in your own way and give it your own twist,” she explains. It’s similar, Maral notes, to the DJ mindset. “We’re all playing the same songs, but it’s how you play it that matters,” she says.

On Push, released through Leaving Records on October 14, Maral explores her passion for the music of Iran in an adventurous way. She plays with beats, samples and noisy electronics to bridge all of her influences, from Crass to Animal Collective to moombahton to David Lynch to the sounds she hears while walking around Los Angeles. Push also includes a track featuring Lee “Scratch” Perry, “Protect U,” which is based on an interview the dub legend did with online radio station Dublab, where Maral also has a show. She collaborated with Penny Rimbaud on “They Not They,” an opportunity that came about when Maral connected with the co-founder of the influential punk band Crass on Twitter.

One of the instruments that you’ll hear on the album is the setar, an Iranian string instrument similar to a lute. As a teenager, Maral learned how to play setar; she played in a Persian classical ensemble as well. On Push, though, she samples setar masters. “Each master has their own specific way of playing the setar,” she explains. Maral wanted to showcase these differing styles. She also samples a Persian flute-like instrument called a ney. “I really love the way that I put distortion on it. It really sounds like you’re shredding on a guitar or something,” she says.

Maral plays a little guitar on the album too, on the track “No Type,” but says that she doesn’t consider herself a professional musician. “I never really figured the music theory part out as well as I should have,” she says. “I let my intuition take me to wherever it wants to.” Intuition is crucial to Maral’s process. “I don’t really know how to use Ableton in the traditional sense either,” she says. “I just played around with it and figured out my own way of using [it].”

Maral was the kid known amongst friends for making mixed CDs. That eventually morphed into DJing with a cracked version of Ableton a friend passed her way. In college, at Virginia Tech, she fell into the same small music scene that would spawn the band Wild Nothing, DJing parties and mixing genres like indie and moombahton and putting her own twist on EDM tracks. Ultimately, DJing led to production, which she has been doing for about a decade. Last year, Maral released her first mixtape, Mahur Club, through Astral Plane Recordings.

Much of Maral’s music stems from her enthusiasm for sharing the sounds that she finds with others. She recalls discovering the late Persian classical and pop singer Hayedeh back when she would dig through her parents’ collection. “I got really obsessed with Hayedeh and wanted to show people her music as much as I could and show people Persian music as much as I could,” she says.

After moving to Los Angeles, about six years ago, Maral had the opportunity to find more music from Iran. She says that’s impacted her work too. “In Virginia, we had a great Persian community. I learned about playing setar, playing all the classical instruments,” she says. “Then, coming to L.A. and having everything be more hyper-Iranian, because of the bigger Iranian population, has been amazing… Getting that chance to reconnect with the culture and having it be so prevalent in L.A. culture is really cool and, I think, important.”

In Westwood, the L.A. neighborhood that’s often associated with Iranian culture, she found CDs that would not just expand her collection of samples, but her musical knowledge as well. “I’m still learning,” she says. “There’s still stuff about Iranian music that I don’t know.”

And, like her production process, Maral lets her intuition guide her digging. “Each time, picking out a random CD from the store, searching YouTube or going through my parents’ tapes, that all really informed me,” she says. “I do it all randomly and go towards whatever my intuition pulls me towards, but I’ve learned a lot in the past five years.”

Follow Maral on Instagram for ongoing updates.