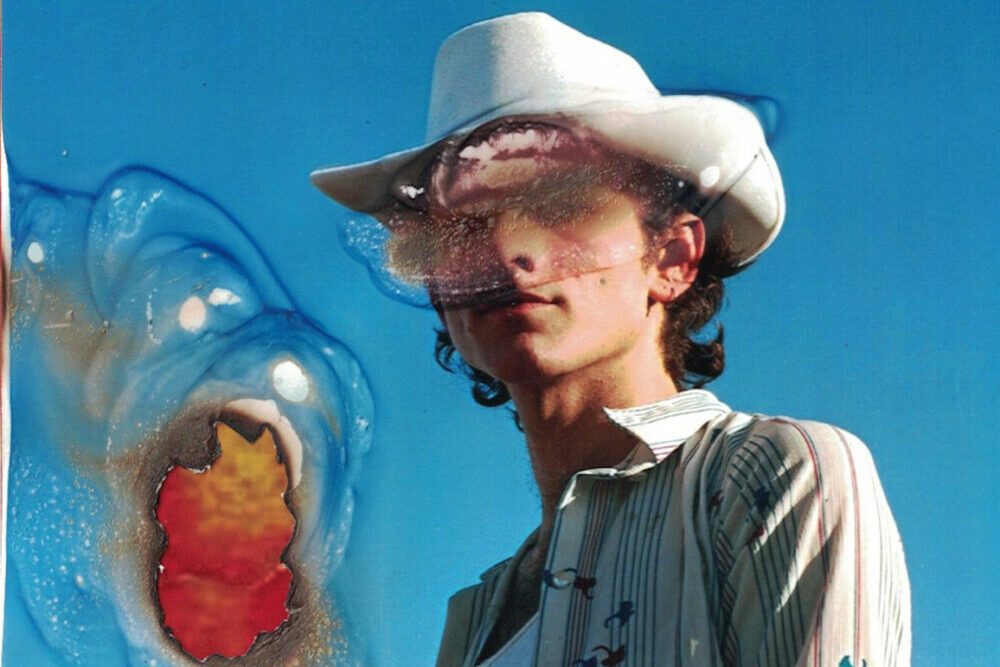

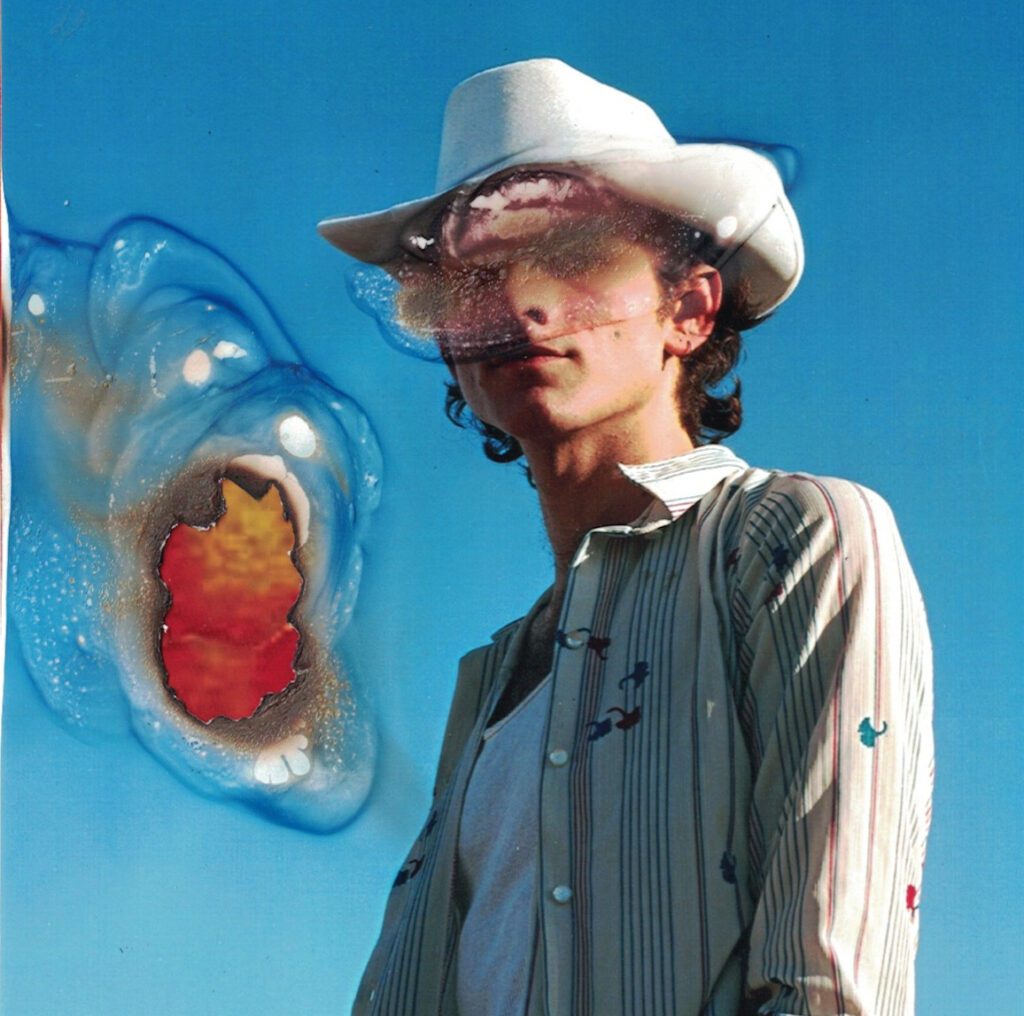

John Errol is on Fire with Genre-Melting Debut LP Inferno

Creating dense, nostalgic soundscapes somewhere between Elliott Smith, Nine Inch Nails, and Britney Spears’ 2007 magnum opus record Blackout, John Errol lands squarely in his own unique, postmodern iteration of pop with debut LP Inferno. Dreamlike production weaves together self-reflective narratives depicting a world of haunting silhouettes, mischievous cowboys, and goth phantoms up to no good. Errol offers us a selective journey into his intimate, pulsating, and immediate songwriting. Each track on Inferno exists as its own mini episode built around nuanced, detail-oriented musical arrangement. The completely self-produced LP swells and expands deeper upon each listen.

With contemporary cutting wit and a dark LA-darling demeanor, Errol has the soul of a seasoned creative veteran, and comes off as a man who’s lived many lives by the tender yet dangerous age of twenty-seven. He’s an internal adventurer ready to guide you into the emotional fires of his musical revolution. In a collection of ten songs, John Errol unleashes a suitcase of inner demons into a nebulous healing chamber, accessible to the rest of us through headphones.

Inferno starts off with “Run Wild,” a poetic intro to Errol’s origin story backed by a Laurie Anderson-esque arpeggiator. “I stared into the sun/Saw a vision that was never mine/I thought, what have I done?/Started out so simple with a piano my granddad gave/He always wanted me to play a song when I was little/But now he says my tune has changed.” The lyrics reflect the musical dichotomy that has sustained and driven Errol since childhood.

Born in London and raised in LA by Turkish and Greek immigrant parents (his maternal grandmother owned the nightclub where his parents met in the ’80s, while his father was on a business trip), Errol has a way of compartmentalizing his backstory with comedic timing and handful of blunt one-liners. “My mom is a failed classical pianist. She’s incredible, don’t get me wrong, way more technically proficient than me,” he says. “But my immigrant grandmother pushed her really hard into a more traditionally Western occupation.” Not allowed to pursue music professionally, Errol’s mother made sure music was a large part of her children’s lives, and an outlet for expression from a very young age.

As a young child, Errol recalls being essentially mute. “An ideal weekend for me was playing the piano, and going to Color Me Mine Pottery studios to paint mermaid statues. I was literally on my own planet,” he recalls. He attended prestigious prep school Harvard Westlake, “which was nothing short of a nightmare,” he says. “I was an overachiever, and I worked my ass off to get there, but… I was in culture shock, and it was a huge wake up call.”

As a teenager he became obsessed with alternative music, taken under the wing of his older cousin. His first large-scale live music experience at the formative age of eleven was Curiosa at The Home Depot Center in Los Angeles. “Growing up, I was very misanthropic, a bit cliché,” he says. “I was cripplingly shy, and the editor of my school’s literary magazine. That demeanor works against me, even to this day; people think I’m an asshole at first glance. As for my music taste, I was listening to a lot of Robert Smith, and got a little Satanic at one point. I was obsessed with Jack Off Jill and Babes in Toyland. I went through a whole punk phase. In terms of the music I played, I kept it safe with just classical piano and jazz guitar.”

Errol took regimented piano lessons from five to fourteen, then segued into the guitar through jazz combos in high school. The early classical training led him to focus on ear training, partially out of dread of sight reading, which enhanced his sonic abilities and allowed him to become a self-sufficient artist and producer, as well as a mixing and mastering machine. The creative control he exerted over Inferno takes a page from the playbook of The Weeknd’s Abel Tesfaye; interestingly enough, Errol recently starred as the masked new wave keyboardist in “Save Your Tears.”

While he doesn’t have to share any of the engineering or creative duties involved with making a record, this visionary quality also drove him into the ground. Inferno was five years in the making, mostly because Errol endlessly rerecorded the tracks, experimenting with various sound palettes. He’d find himself up until the sunrise dragging amps into the shower, just for the reverb plate of the bathroom’s tile walls. It took a global pandemic for the record to be marked complete.

Making a record over the course of five years becomes an interesting journey because throughout the creative process the industry had dramatically shifted. “Spotify runs the world, essentially. And it’s created a genre of music unto itself, a hazy innocuous bedroom pop which I personally fucking hate,” Errol scoffs. “A quote I saw on Twitter summed it up so well: Songs are the new albums, playlists are the new artists. It was one of the most disturbing yet accurate summaries of what has happened to the musical landscape.”

Inferno stands in contrast to that model, demanding to be consumed as a comprehensive work of pop art. Its centerpiece is the eight-minute-plus “Blue Flame,” a multi-dimensional coming of age story. “Muted dreams won’t give you many signs to read/Better do what you’re told/And swallow your pride/A path has been laid in a prison built along the line,” Errol sings, his voice drenched in deeply resonating vocoder, merging classical piano with industrial synthetic drums, infectious guitar leads, and soothingly smooth melancholic yet melodic top lines. After many iterations of the track, he nailed it.

Though he could easily be a phantom figure from the future, traveling back in time, swaying under pink stage lights in a hazy Lynchian fog to an ’80s beat in a discotheque, the actual path that led Errol to present day is almost more interesting. The contrarian found his way to the East Coast, attending Bard College. “I had this idea of LA being this vapid center of bimbo culture. Now there’s a very established art scene, but as a kid I was never really around people who were interested in the same things,” he says. “At Bard, I entered this universe where there were people like me. I met my closest friends and collaborators. I think it was my second day, I met Adinah [Dancyger] who directed [my music videos].”

During his formative years Errol took a weekend job in New York City, crashing at a friend’s NYU dorm, and began keeping an ear to the ground for modern music in the New York scene. He snatched up his first professional music industry gig while working retail at Opening Ceremony, when he stumbled into buzz band Starred; after professing his admiration, they scooped him up to play keyboards on their tour with Courtney Love. “I was just stunned every night getting to watch her, because as a kid I was actually a major Courtney Love fan,” Errol says. “For my sixth grade talent show at my Catholic school in KoreaTown, I sat on the stage and played and sang a rendition of ‘Doll Parts’ – just chubby little me in a Catholic uniform. It was dramatic, and I was just so clearly a homosexual.”

When Starred disbanded, Errol re-emerged with with the knowledge that he wanted to pursue music professionally; he was no longer the kid at Kulak’s Woodshed Monday Open Mic on Laurel Canyon drowning himself in Elliott Smith-inspired laments (what the bubbly yet self-deprecating Erroll calls “the worst music of all time – how could I have gone out to sing those songs?”). He finished up at Bard with a thesis on Faulkner, but as his idiosyncratic blend of everything from industrial to country began to take shape, he found there were few who understood his vision.

“Past managers I tried to work with would say, what is all this insane, crazy industrial stuff you’re making? It’s incohesive, don’t do that. Don’t waste your time with it,” Erroll says. “I want to try a million different outfits, and find a common thread between all of them. I’m not as interested in focusing on songs that will ‘do well,’ because I don’t think pop music is guaranteed to do well or have a certain outcome.”

After parting ways from various managers and agents, Errol sought solitude and sobriety to regain his sense of purpose and center from the highs and lows of too much industry attention too soon. “Being in the process of assembling a professional team, while struggling with addiction, made me incapable of finishing music,” Errol says. “I just had this wall and blockage. I was a living cliché of the saying, ‘You’re your own worst enemy.’ That really was my main problem, and why it took me five years to finish the record.” Separating himself from his self-destructive tendencies, he instead found solace in 5am studio sessions. Now self-managed under the guidance of his distro company Terrible Records, Errol feels secure in following his own artistic and musical instincts.

On “Unbelievable” he describes these trials and tribulations, as well as the discomfort of self-marketing. His magnetic, twisted persona shines and his wit reigns free in the video’s satanic rituals, campy red gels, blood, gore, chaos and, surprisingly, choreography. Errol croons, “I lied my age/I stole my name/My head keeps spinning/And I can’t seem to stop/A million lies/I can’t rewind/A life that isn’t there/I am unbelievable.”

That self awareness only adds to John Errol’s mystique and charm as a brilliant and truly actualized artist. Through making Inferno, he has come to terms with personal demons, from his battle with addiction to his struggle with mental health, and the resulting album resonates themes of personal growth, happiness, and self acceptance. After a year of sobriety (during a global pandemic no less), John Errol has emerged as one of music’s most exciting up-and-coming queer indie pop stars.

Follow John Errol on Instagram and Facebook for ongoing updates.