How I Fell in Love With 7-inch Singles and Why They Still Matter

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Beth Winegarner flips through an old collection and finds it relevant even today.

When I was a teenager, I had a ritual every Saturday afternoon. My mom and I would go to Coddingtown, the Santa Rosa shopping center immortalized on Primus’ Brown Album, and I would make a beeline for International Imports, which sold rock-band posters and T-shirts and had a small, well-curated rack of 7-inch vinyl singles.

I was methodical. I would flip through the singles alphabetically, fingertips brushing against the colorful paper sleeves, working my way from A-Ha to Dweezil Zappa. I wasn’t a completist; I didn’t need copies of every single, not even every single by my favorite musicians. With an allowance of five bucks a week, I couldn’t afford to be.

My love of music started when I was about 10, with albums like Cyndi Lauper’s She’s So Unusual, Duran Duran’s Seven and the Ragged Tiger and Madonna’s self-titled debut. I spent my afternoons and weekends listening to them over and over, flipping the cassettes every 20 minutes in my cheap plastic boombox. When an album didn’t come with a lyric sheet, I would lie on the floor in my room with a notepad and pencil, the tape deck close by, stopping the tape after every line to write down the words, rewinding when I needed to hear it again to puzzle out what they were singing.

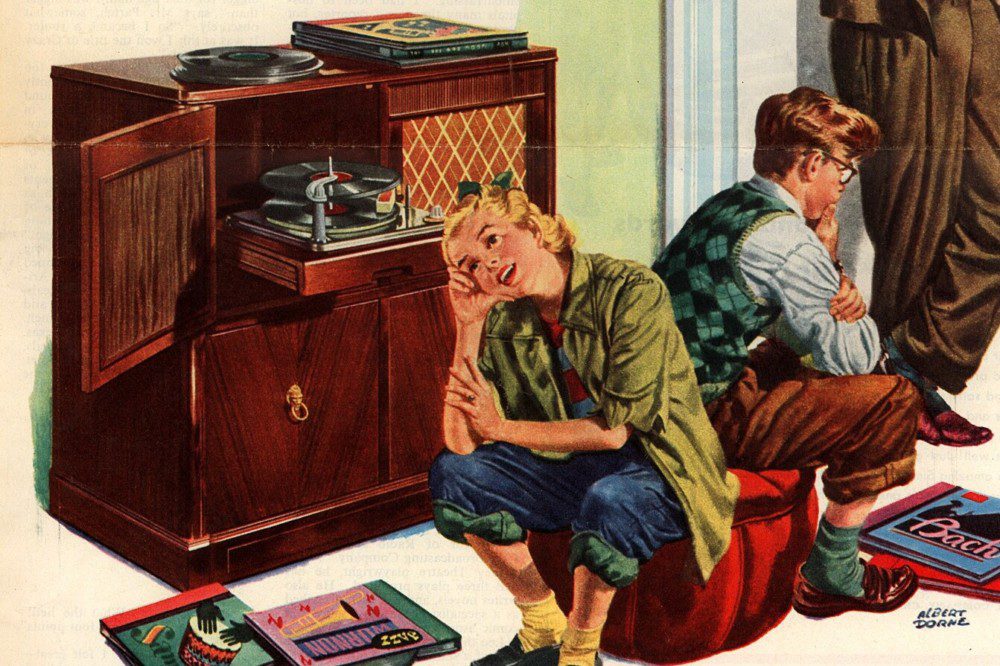

Music dropped me straight down into my feelings, which were swirling thanks to puberty. Music made me want to cry, laugh, move my body. It made me want to kiss the boy in my class that I’d had a crush on since fourth grade. I felt it in my heart, my belly, my arms and legs, my stomping feet. Nothing else came close to making me feel so good, or feel so much.

Sometimes I saved up my money to buy full albums on cassette, but there was always a risk that those albums were just a few hit songs and a lot of boring filler. Seven-inch singles were cheaper, and you were guaranteed at least one good song; often the B-side was great, but other times it was a dud. Partly because of the posters and t-shirts, International Imports was my favorite place to shop for singles, even though it didn’t always have the best selection. Some Saturdays the rack looked like it had been picked clean by collectors, down to its last Debbie Gibson or Phil Collins 45s.

Over time, I built a small collection of about 50 singles, several of which are now considered classics. Among them are Bon Jovi’s “Wanted Dead or Alive” (backed with “I’d Die For You”), The Cure’s “Just Like Heaven” (b/w “Breathe,” which I immediately loved more than its poppy, whirling A-side), INXS’s “Devil Inside” (b/w “On The Rocks,” an unreleased track) and Prince’s “When Doves Cry” (b/w “17 Days”).

Many others are one-hit wonders only a teenager in the mid-1980s could love. Does anyone else remember Icehouse’s “Electric Blue,” Noel’s “Like a Child,” Times Two’s “Strange But True,” The System’s “Don’t Disturb This Groove” or Pebbles’ “Girlfriend?” If you’re a true aficionado of ‘80s music, sure. I have them all on 7-inch vinyl, and I’m not sure I would still remember them if I didn’t.

Although we shopped regularly in Santa Rosa, a medium-sized Northern California city, I lived 12 miles away in Forestville, an unincorporated town that had a population of just a few thousand. We didn’t get access to cable television – and hence MTV – until 1987. Before then, I relied on popular radio stations and the DJs at our school dances to find out about new music, and as a result my tastes were strictly mainstream. The vast majority of the singles I bought were from stars popular with teens, including Tiffany, Duran Duran, Madonna and Wham! But several are a reminder of how R&B and rap mingled with pop at the top of the charts, then as now: Rockwell, Terence Trent D’Arby, New Edition, Billy Ocean, Salt N’ Pepa.

The Saturday-afternoon Coddingtown visits were only part of the ritual. Once we got home, I would immediately listen to any singles I’d picked up. We had a respectably nice Sony record player in our family room, although that meant either subjecting my parents and little brother to the latest hits, or sitting on the floor with headphones as the songs played in my ears, since the cord didn’t reach to the couch or my dad’s recliner. More commonly, I listened to them in my room with the doors closed. I had one of those portable turntables that folds up like a small plastic suitcase, the outside decorated to look like it was made of patchwork denim. The turntable’s small, single speaker made everything sound tinny and far away, but being able to enjoy my favorite songs on my own terms made up for a lot.

I dreamed of buying a jukebox – I could load all my 45s in it, and choose among them at the push of a button! The sound quality would be much better, and I could listen to a dozen songs in a row without having to get up and change the record every three to five minutes. I had no idea, at the time, how much a jukebox would cost. Finally I saw one listed in my dad’s Sharper Image catalogue, and my heart stopped when I saw the price: about $10,000. There was no way I would ever be able to afford that, and no way I could convince my parents to buy one for me.

My love of 45s came just as the format was on its way out. Seven-inch singles existed throughout the 20th century, and were hugely popular in the 1950s through the 1970s, when they made popular music easily portable for the first time. Sales were already on the wane by the 1980s, although it was still standard procedure for pop artists to release their latest hits on 45-rpm vinyl. Some record companies lured buyers by wrapping the singles in a large poster, folded to create a kind of envelope, although that left you without a sleeve if you wanted to put the poster up. My copy of Duran Duran’s “The Reflex” spends its days in a sleeve I made out of printer paper after I pinned the promotional poster to my wall. The poster is long gone, but the paper sleeve I made remains.

Seven-inch singles carried me through from the beginning of my passion for music until 1987, the year I turned 14. It was a year of big shifts, both for me and for the 7-inch single. That was the year American record companies largely abandoned vinyl singles in favor of the cassette single, the unfortunately nicknamed “cassingle.” It was also the year I gained access to MTV and the year I entered high school, leaving my pre-teen tastes behind me. Glam-metal and hard rock were on the rise, particularly bands such as Dokken, Poison, Guns N’ Roses, Motley Crue and Whitesnake. My collection of 45s reflects this; some of my last purchases include “Wanted Dead Or Alive” and Def Leppard’s “Love Bites” (b/w a live version of “Billy’s Got a Gun”).

International Imports stopped selling 7-inch singles and I stopped buying them, although I kept visiting for things like posters and shirts, plus more “international” items like funky jewelry and nag champa incense. I turned away from pop and R&B and towards anything featuring electric guitars and scruffy-looking male howlers. And instead of buying cassingles – which needed flipping just as often as a 45 but lacked the elegant ritual of moving the needle, turning the vinyl over and setting the needle in the groove – I recorded videos from MTV’s Hard 60 and Headbanger’s Ball and watched them repeatedly until my tapes just about gave out.

I still have all my 45s, tucked alphabetically inside a specially designed box on a shelf with the rest of my vinyl records. I rarely listen to them anymore, but I can’t bear to sell them or give them away. A few musicians today release their singles on 7-inch records, mainly as collectors items, but it’s rarely musicians whose music I love. The most recent vinyl single in my hoard is “Backworlds” by Lusk, a psychedelic rock band co-founded by former Tool bassist Paul D’Amour; I received it as a promo when I wrote a feature about Lusk in 1997.

Record collecting is often thought of as a man’s activity, epitomized in Nick Horby’s High Fidelity (and the movie based on it). There’s an assumption that only men would be so obsessive, so knowledgeable, so nerdy – or that it’s a club to which women are not allowed to belong. As academic Emily Easton has pointed out, research on record collecting has pretty much excluded women, even though there are plenty of female vinyl nerds out there. “Records remain one of the most important forms of objectified cultural capital in many musical communities because they have been recognized as a symbol of musical expertise and investment,” Easton says. “Understanding how women have participated in these practices contributes to an emerging body of knowledge on the experience of the female music fans and connoisseurs.”

Flipping through the singles at International Imports, it never occurred to me that my passion for collecting 45s might make me part of an unusual or under-recognized family of music fans (I mean, when Rob Gordon says he’s rearranging his albums chronologically, I knew exactly what he meant). I only knew I was following my 10-, 12-, or 14-year-old heart, bringing home the songs I loved in a format that felt good in my hands and sounded good on the turntable. Knowing now that female vinyl collectors have been sidelined and ignored makes me want to clutch my records to my chest in defiance and never give them up. Maybe someday I’ll buy myself that jukebox after all. I’ll push the buttons, flip “Pump Up The Volume” by M/A/R/R/S or “Paranoimia” by Art of Noise (featuring Max Headroom) onto the player, and dance.