Maila Nurmi came to Hollywood in the 1940s, dreaming of fame and fortune. And after more than a decade of ups and downs, she had, briefly, attained it. She achieved international renown as Vampira, the world’s first horror movie TV host, setting the standard for what a horror queen femme fatale should aspire to, as well as laying the groundwork for the goth look decades before its time. Her cult status was further assured by her role in Ed Wood’s classic no-budget feature Plan 9 From Outer Space. And over the course of her eventful life, she crossed paths with numerous legends: James Dean, Orson Welles, Marlon Brando, Elvis Presley.

But that was then. When her niece, Sandra Niemi, cleared out her aunt’s apartment after her death in 2008, she found that Maila Nurmi had died in poverty. The only pieces of furniture she owned were a sofa and a plastic patio chair. Friends had often paid her rent, or the phone bill. But amidst her other possessions — the clothes, the memorabilia, the 30 pounds of beads — Sandra made an astonishing discovery. Maila had been chronicling her story over the years, “Pages and pages and pages of handwritten writings,” Sandra says. “Letters that she either forgot to mail, or it was a first draft. Scraps of paper, just a sentence or two, written in the margin of a calendar or a newspaper. Or just a scrap of paper by itself, sometimes wadded up and put in a pocket of an old jacket or a purse. Just a memory here and a memory there.”

When Sandra gathered up all the bits and pieces, they filled two plastic garbage bags. “I knew I had to put this together. And I wasn’t thinking ‘book.’ I was thinking, I’m going to find out who Maila is, and what she did with her life. What I always wanted to know and never could find out.”

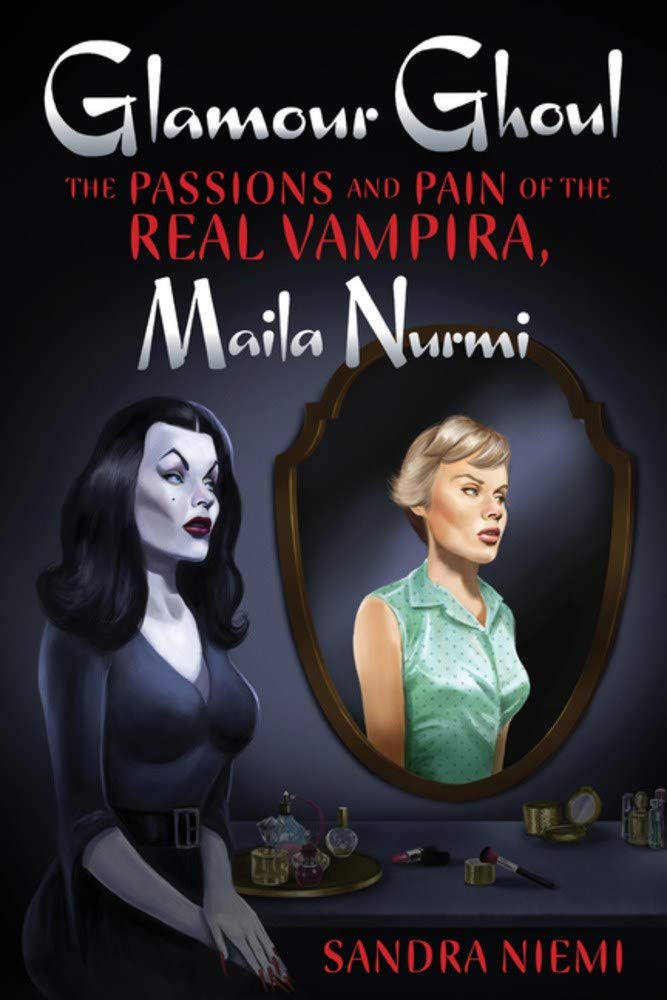

But this was a tale that begged to be told to a wider audience, and over the next twelve years, Maila Nurmi’s niece sifted through her aunt’s writings, added her own research, and finally published Glamour Ghoul: The Passions and Pain of the Real Vampira, Maila Nurmi (Feral House). It’s the remarkable story of a cultural icon, whose personal idiosyncrasies curtailed a career that might have gone further, while her disdain of anything that smacked of conventionality meant she was a stranger to her own family. “I got to thinking, I’m the only one that has all this information about Maila,” Sandra explains. “There was more to her than just Vampira; that was such a brief part of her life. I thought, you’ve got to do a book, because if you don’t, Maila will only be a footnote in history. I didn’t want her to be a footnote. She deserved a lot more than that.”

Maila Nurmi was born Maila Elizabeth Niemi to Finnish parents on December 11, 1922, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Her father moved the family frequently as he pursued a career as a journalist and editor, and by the time Maila graduated from high school, she was living on the other side of the country, in the coastal town of Astoria, Oregon. Not wishing to be sentenced to a lifetime’s work the local fish cannery, Maila escaped to Los Angeles in 1941, appeasing her father’s disapproval by initially living with relatives.

Her early attempts to launch a career provided a rude awakening. A talent agent, luring her with prospects of future work, persuaded her to pose topless, after which no future work materialized. She escaped assault from another agent by smacking him in the eye. “No more showbusiness for me,” she wrote on one of those scraps of paper. “Everyone concerned is FILTHY!”

But still, she persisted. She eventually found work as a model. While living in New York, she appeared in Catherine Was Great with Mae West. Her dancing skeleton routine in the show Spook Scandals landed her a screen test with noted director Howard Hawks. But then her independent streak kicked in. Outraged that Hawks said she’d need to get her teeth fixed, she tore up her contract, told the director, “I am not a commodity to be traded or sold to the highest bidder!” and stalked out of the office, to his astonishment.

“She shut the door on any movie career she would have had,” Sandra observes. “And she very well could have had a great career. She was insulted that he thought she was less than perfect. And she didn’t want her teeth fixed; she was afraid of dentists. So that was the end of that. Of course, she was young; twenty-one, twenty-two, thinking, ‘Well, the world is my oyster. I can have any job I want. I don’t need him.’ And she did need him. But she did it her own way.”

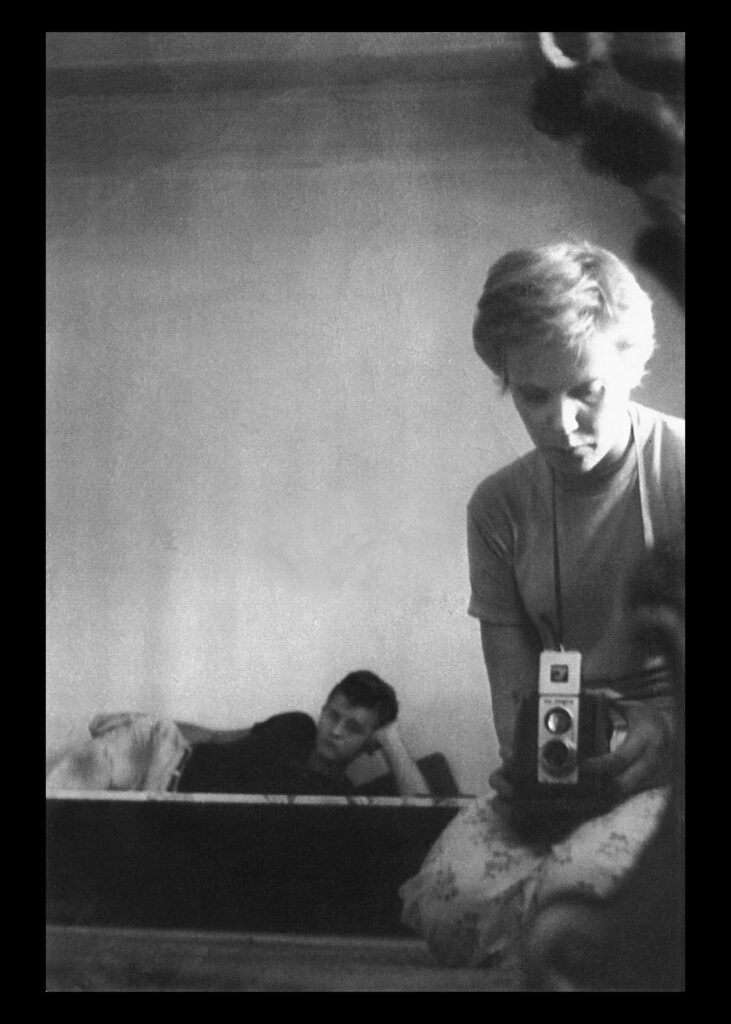

Maila continued working on the fringes of the entertainment industry, getting gigs as a model, a photographer’s assistant, in the chorus line, bit parts in films. A liaison with Orson Welles brought no physical pleasure (“Orson was not a gentle lover and was possessed of an urgency to complete the act”), but did result in the birth of a son, who was given up for adoption. Childbirth proved to be such an excruciating experience she vowed to never again have children.

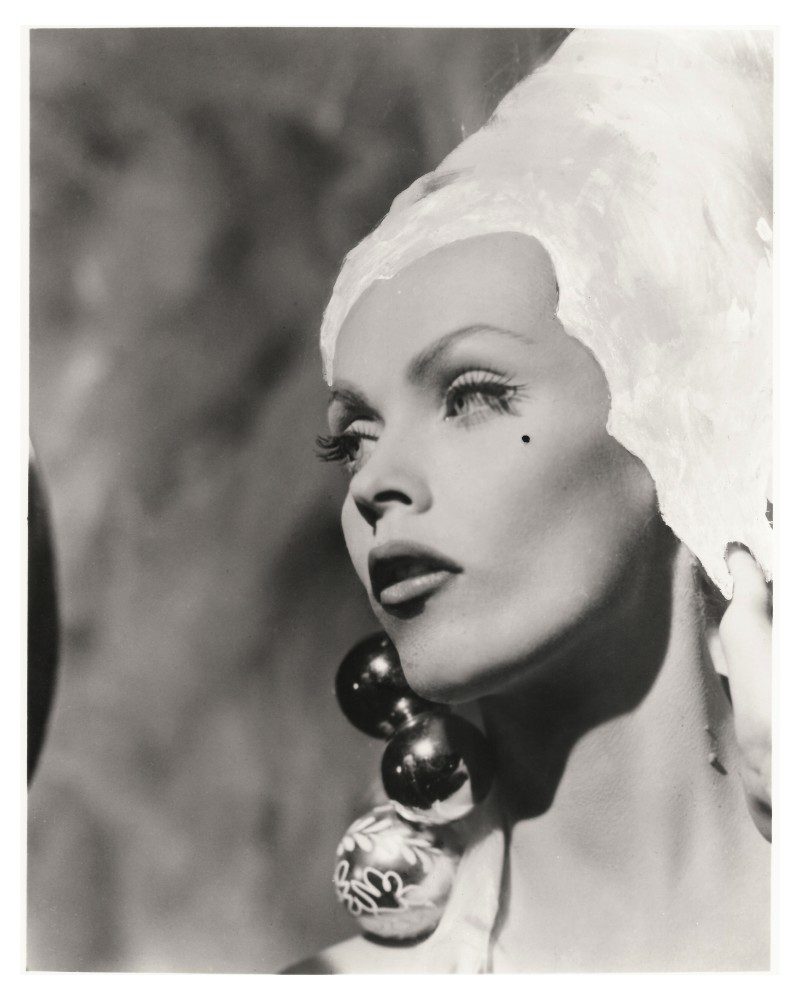

She could still play the part of a star even if she wasn’t one yet. Sandra was enamored when she first met her aunt in 1953, as a six-year-old. “I had never seen anyone so beautiful,” she says. “She walked out of the back bedroom to make her entrance — now I know that’s what she was doing — and she was the most gorgeous thing I’d ever seen.” Wearing a shimmering gold lamé dress, shoes with transparent heels, and colorful makeup (bright blue eye shadow that went “from the eyelashes all the way up to her eyebrow,” vibrant red lipstick), she seemed like something out of a fairytale. “I was looking at this goddess thinking, wow, that’s my aunt Maila! She was my own private Cinderella.”

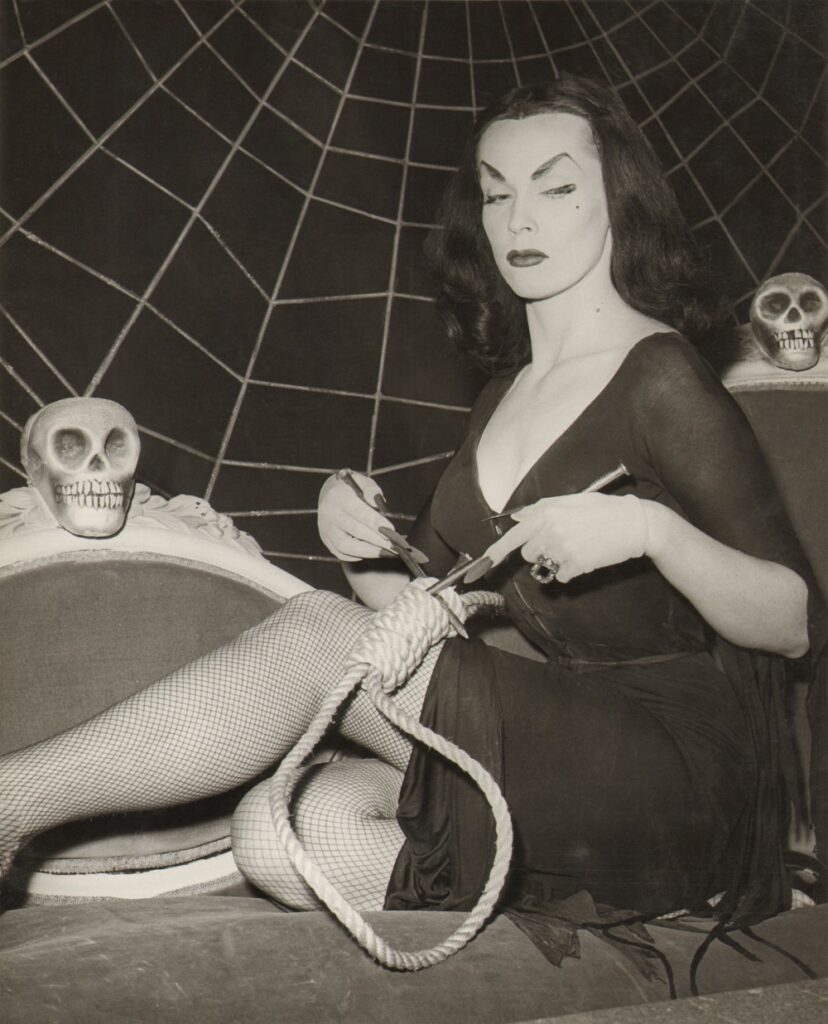

The next year, Maila’s moment arrived. Her prize-winning attire as a black-shrouded zombie (inspired by the cartoons of Charles Addams) at a costume ball attracted the attention of Hunt Stromberg, Jr., KABC-TV’s program director, who was looking for someone to host the station’s screenings of old horror films. Maila decided to sex the character up for her audition, turning the black dress around so the zipper was in front, cinching her already slender waist (the result of excessive dieting), and padding her bust and hips. A black wig and three-inch fingernails provided the final ghoulish touches. Vampira was born.

Nightmare Attic, soon to be renamed The Vampira Show, debuted on May 1, 1954. Vampira opened the shows by slinking down a cobwebbed hallway toward the camera, finally erupting in a blood-curdling scream. She delivered black-humored commentary (“I went to a delightful funeral yesterday. We buried a friend of mine — alive”) while sipping on cocktails like the “Mortician’s Martini” (one part formaldehyde, one part rattlesnake venom, a dash of culture blood, garnished with an eyeball). She was an immediate sensation, and Maila found herself being inundated with requests for personal appearances, profiled in Life, Newsweek, and TV Guide, and an in-demand guest at film premieres. Stardom was hers for the taking.

But her explosive success burned out all too soon. She soon came into conflict with the station’s management, resenting their attempts to pair her with the host for their romance film slot, a softer character named “Voluptua.” She had to learn to get along with her bosses, she was told. But as always, she did things her own way. Things came to a crashing halt in 1955 when she disobeyed KABC’s demand that she not appear on a rival network’s program; the infraction led to The Vampira Show being cancelled. There was a short-lived revival the following year on KHJ-TV. But Maila felt the show was hampered by the poor quality of the writers, and it was cancelled after 12 episodes. Vampira’s run was over.

There were also personal disappointments. Her common-law marriage to screenwriter Dean “Dink” Riesner ended. She was shattered by the death of her close friend, James Dean in 1955. “She felt like he was the first person she ever, ever met that was from the same planet,” Sandra says. “And then he was gone and she was alone again. She never got over his death, ever.”

Her relationship with her family fractured as well. When Maila’s mother died in 1957, Sandra and parents came to LA for the funeral. To Sandra, the Cinderella princess was now a “sad girl in rags,” who didn’t change her clothes during the entire visit. “She asked my mother, ‘What are you going to wear to the funeral?’ And my mother thought, ‘Oh, thank God, she’s going to change her clothes!’ But she didn’t. She just turned her sweater inside out. And I’m sure now, looking back on it, it was to say, ‘My life has been turned inside out.’”

It was the last time Maila would ever see her brother Bobbie. “My father wanted to have a relationship with his sister,” Sandra says. “But to Maila, he represented everything she despised. He and my mother had built this little tiny two-bedroom house, and he had a job, and he had a family. And that’s everything she did not want. She did not want to be domestic in any way.” An invitation to visit Astoria was rejected. Maila dropped out of sight. “I’d say to my dad, ‘I wonder where she is, I wonder what she’s doing.’ And he’d say, ‘Well, you know, she doesn’t want to be found.’”

Maila did what she could to get by as her opportunities seemed to dry up; she had small parts in films like Plan 9, The Beat Generation, Sex Kittens Go to College. She worked as a housecleaner. She entered into a short marriage of convenience with Italian actor Fabrizio Mioni. She owned an antique shop, Vampira’s Attic. She perused swap meets, dressed up her finds with feathers and beads, then sold her wares from a table on the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Havenhurst Drive (Grace Slick and Shelley Winters were customers). She provided fire-and-brimstone recitations on the single “I’m Damned”/“Genocide Utopia” by garage rockers Satan’s Cheerleaders. She moved frequently, and changed her name more than once. Marlon Brando, a former paramour, sent her money when she was hard up.

Sandra never stopped wondering what happened to her aunt. “I knew nothing about her,” she says, “And I was always obsessed with finding out. I had written to many, many newspapers, magazines, and television shows, asking if anybody knew where Maila Nurmi was, Maila Nurmi who had been Vampira. I never got one response. So I didn’t know if she was dead or alive.” When Sandra’s father died in 1977, she asked the Red Cross for help in finding her aunt so that she could let her know he had passed. “They couldn’t find her. Little did I know that she was going under the alias of ‘Helen Heaven’ then.”

Then, in October 1988, Sandra spied an item in Star magazine about a lawsuit Maila had filed against KHJ-TV actress Cassandra Peterson and other associated parties over their syndicated show Elvira’s Movie Macabre, which she contended infringed upon the trademark she held for Vampira (Maila ultimately lost the case). Sandra reached out to Maila through her attorneys, and soon her long-lost aunt replied with an eleven-page letter. “To think that Bobbie has died and I didn’t know,” she wrote. “Shame on me.”

In August 1989, Sandra and her daughter Amy drove to LA for a visit. “Maila was living in a reconverted garage with no refrigerator and no stove,” she recalls. “She had a hot plate. And just a toilet. She didn’t have a shower; she had to wash out of the sink. And there was one window in the living room, way up high like you would find in a garage, and that’s where Stinky Two lived. He was an abandoned bird that couldn’t fly, so Maila took him in and he lived there up on the window ledge.”

Despite the lack of amenities, hey had a wonderful time. As they drove around town, Maila regaled them with anecdotes and pointed out sights of interest (“That’s the hospital where all the celebrities go to dry out or die”). They splurged for a brunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel, running into I Dream of Jeannie star Barbara Eden and getting her autograph. They drove to Griffith Park, where scenes from Rebel Without a Cause had been shot, to see the commemorative bust of James Dean. And the stories never stopped. “Maila never lacked for commentary,” Sandra chuckles. “She loved gossip, and she had lots of gossip to say.”

On their last night together, Maila unearthed some treasures for Sandra: family photos, Vampira scripts, a love letter from Marlon Brando proposing marriage (Maila turned him down: “He was a sex addict and a hypocrite”). She talked about Orson Welles, and the son she’d given up, wondering where was he was now. She recalled her brief affair with Elvis, whom she’d met in Las Vegas (“The way he moved those hips on stage, I was expecting a symphony, but I got Johnny One-Note”). They ended the night by singing the Finnish national anthem, and went to sleep on the floor, as Maila had no bed. Sandra told her aunt the week they’d spent together had been one of the best times of her life.

The two corresponded until 1991. Then, once again, Maila dropped out of sight. She was often without a working phone (and wouldn’t always answer when she had one), and when she moved again, Sandra couldn’t even reach her by letter. She never knew why her aunt stopped writing, but thinks it may be because Maila’s life was becoming more active. The 1980 book The Golden Turkey Awards had named Plan 9 as “the worst movie of all time,” rekindling interest in the film and its director, Ed Wood. She was interviewed for Rudolph Grey’s 1992 book Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr., and Tim Burton’s 1994 bio pic Ed Wood raised her profile even higher. “She was in demand,” says Sandra, “and I guess she just blossomed.” Maila had been on disability since she was diagnosed with pernicious anemia at age 46, which impaired her ability to walk. The income she received from convention and film appearances was most welcome. She also began painting, and selling her work online.

On January 10, 2008, Maila was found dead in her apartment, due to heart failure. She was 86. Sandra read about her aunt’s death in the paper, and headed to LA. “Through what can only be described as a miracle,” she finally found her aunt’s last residence, and the written record of her life that she’d worked on for decades.

Work on the book was a challenge. Some of Maila’s writings were dated, others were not. “Some were just a sentence or two; who she hated now, what they had done to her. One was an ‘Autistic List.’ I showed it to her friend Stuart Timmons, and I said, ‘You’re on this list. Do you think maybe she meant Artistic List? And he goes, ‘No. It’s Autistic.’” There were also the understandable nerves of a first-time author. “I’d write a little bit and think, well, this is crap. Nobody cares. I mean, horrible, horrible self-doubt. Awful, awful. Put it away for a year. Come back to it. It just haunted me.”

Then inspiration arrived, via a twist that nobody was expecting. In 2017, Sandra had given her daughter a DNA kit from Ancestry.com as a Christmas gift. Two years later, Amy came up with a match, and delivered the stunning results to her mother: “I know who Maila’s son is. I know his name. I know where he lives and I know his phone number.” Maila’s son, whom she claimed was the offspring of Orson Welles, turned out to be David Putter, a retired lawyer who’d served as an assistant attorney general for the state of Vermont. David had never known his birth parents, and his adoptive mother died when he was four. “So he’s kind of a motherless waif,” says Sandra.

In their first phone conversation, David asked Sandra if she knew who his birth mother was. “I said, ‘Oh, do I know who your mother is? You’re talking to the only person on the planet that is just finishing up her biography!’ Then I told him that she was Maila Nurmi — Vampira. And he said, ‘Oh my God. I waited seventy-five years to find out who my mother is. And I find out that she’s a vampire!’”

Finding Maila’s son broke through Sandra’s writer’s block, and the biography was finally finished. “I just wanted Maila’s story to be out there because she deserved it,” says Sandra. “She deserved a little immortality, and I was the only one that could do it. I wanted people to know that she was very intelligent. She was funny. She was extremely creative, resourceful, and she never sold out. People all through her life tried to buy Vampira. And as poor and poverty stricken as she was, she never sold out. She hung on to Vampira, until her last breath.”

Today, Maila Nurmi can be found at one of her favorite places: the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, situated behind the Paramount Studios lot, and the final resting place for luminaries like Judy Garland, silent screen star Rudolph Valentino, Wizard of Oz director Victor Fleming, and singer Yma Sumac. It was paid for by her friend, Dana Gould, whom Maila met when he was the host of The Big Scary Movie Show on the Sci-Fi Network. “She’s right on the roadway, and directly across the roadway is the huge lake with swans on it, the most beautiful spot in the entire cemetery. She has a primo spot; I couldn’t have handpicked a better place for her to be,” says Sandra.

“And Maila spent a lot of time in that cemetery. I have pictures of her in Hollywood Forever, sitting on one of the great director’s tombstones,” she adds. “She liked to be there. Her friend Greg Herger told me they went there often, and would have their lunch and just sit there and talk. She’d said, ‘I love this place,’ and now she’s there. I’m thrilled with where she is.” An image of Maila as Vampira is on her headstone. And when you look at it, you can almost hear her saying, “This is Vampira, until next week, wishing you bad dreams, darling.”