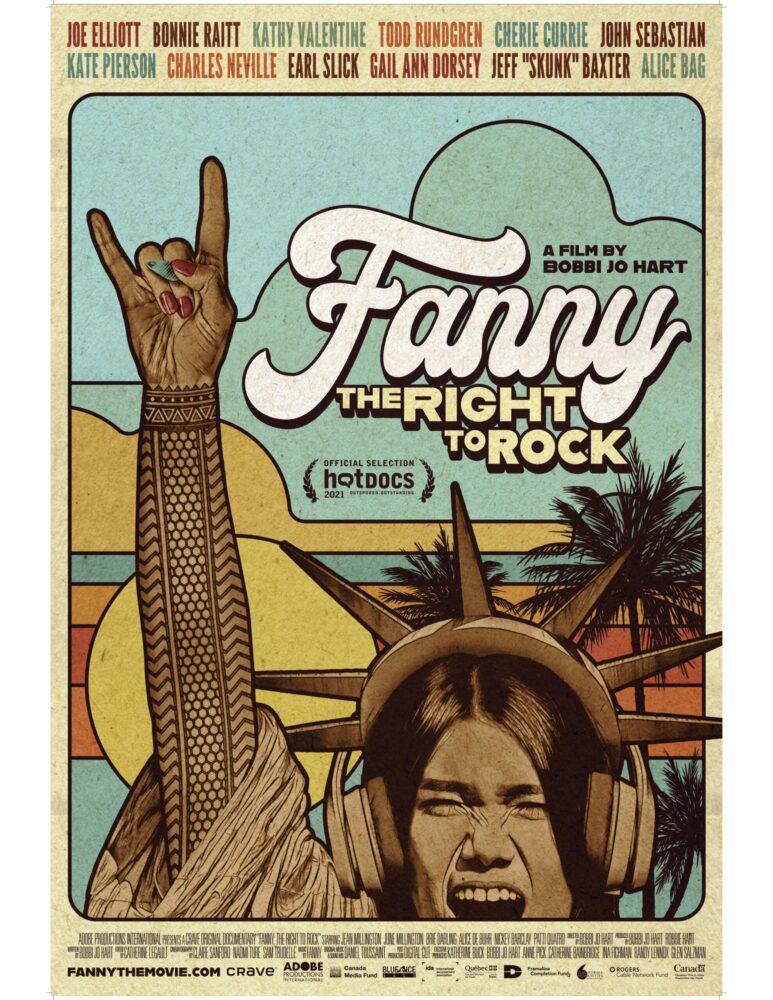

Fanny: The Right to Rock finally brings the story of the legendary all-female band to the big screen. Director Bobbi Jo Hart traces Fanny’s journey from the early ’60s formation of Sacramento-based band the Svelts (Filipina sisters Jean and June Millington’s first act), to their transition into Fanny by the end of the decade, the band’s breakup in the mid-1970s, and the reunion on the 2018 album Fanny Walked the Earth. The film had its world premiere in Toronto last April at the Hot Docs festival (winning the Audience Choice Award), the US premiere following in June at the FRAMELINE Film Festival in San Francisco. With more festival screenings leading up to a theatrical release scheduled for the fall, Audiofemme got the chance to talk to Alice de Buhr, Fanny’s drummer. “I thought that Bobbi Jo did a fantastic job,” she says. “It’s a good story arc, and I think she pulled it together quite nicely.”

For de Buhr, who runs the band’s official website and hosts the podcast Get Behind Fanny, the film is “another tool in my tool belt” to keep spreading the word about the group. “What I’m really looking for, is when people say, ‘Have you heard of Fanny?’ they go, ‘Oh yeah, I know them.’ That’s what I want. Instead of ‘No, I’ve never heard of them.’” de Buhr says. “I would like for Fanny to be more well-known and for people know who we were and what we did. Because I think it’s important.”

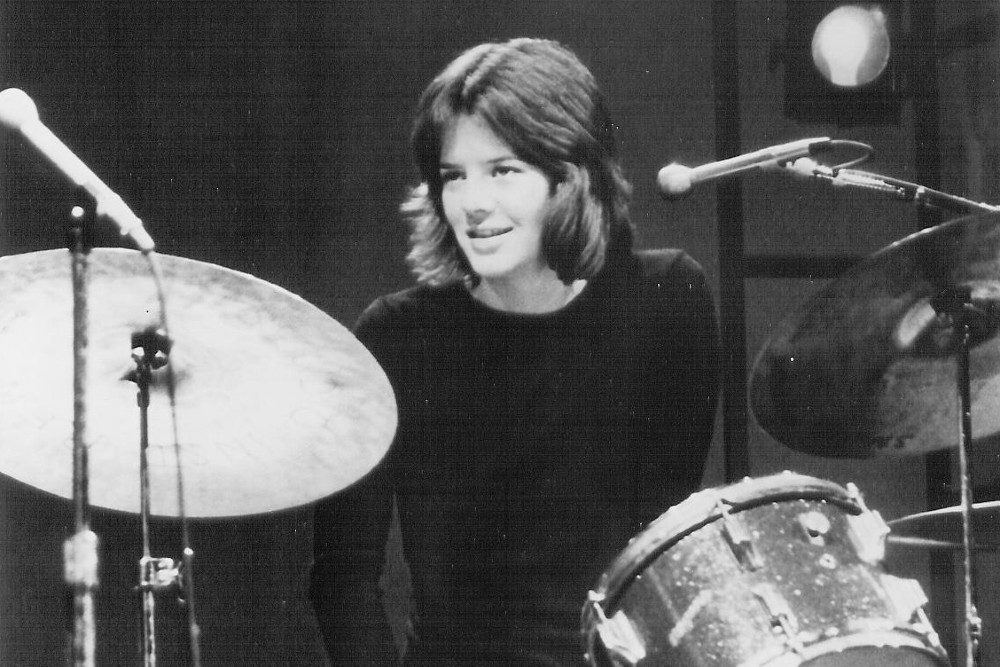

De Buhr’s path to Fanny began when she was in the second grade, in Mason City, Iowa. Her school’s band director tapped her to join the band as a drummer. De Buhr readily took to the instrument, and by high school she was playing in her first all-female band, the Women. “We played Beach Boys, Beatles, Motown — whatever was on the radio,” she recalls. “One of the first songs we learned was [Tommy Roe’s] ‘Oh Sweet Pea.’ I hate that song to this day!”

After what she describes as a “horrible coming out in a small town” experience, she and her girlfriend left for Sacramento. While looking for a band to play with, de Buhr took any job she could find. “We got a job selling Kirby vacuum cleaners, and we cleaned apartments,” she says. “Collecting pop bottles to get fourteen cents so that we could buy Kraft Macaroni and Cheese — which has taken me years to be able to eat that again.”

Eventually, de Buhr responded to an ad the Millingtons placed looking for a drummer, and, while waiting to hear back, briefly played in a band with three men. “I think everybody thought I was a guy too, with really long hair, because I was pretty flat chested for a long time,” she jokes. The Millingtons finally got in touch, and de Buhr joined the Svelts, only to leave the group with Svelts’ guitarist Addie Clement to form another band, Wild Honey.

But they soon realized how much they missed playing with the Millingtons. “June was the best rhythm guitar player I ever played with,” says de Buhr. “We were in the pocket from almost the beginning. That rhythm section that she and I created was heaven, heaven to play with her. Addie and I decided very shortly that it wasn’t going to happen with either of our bands separated. So we buried the hatchet and got back together.”

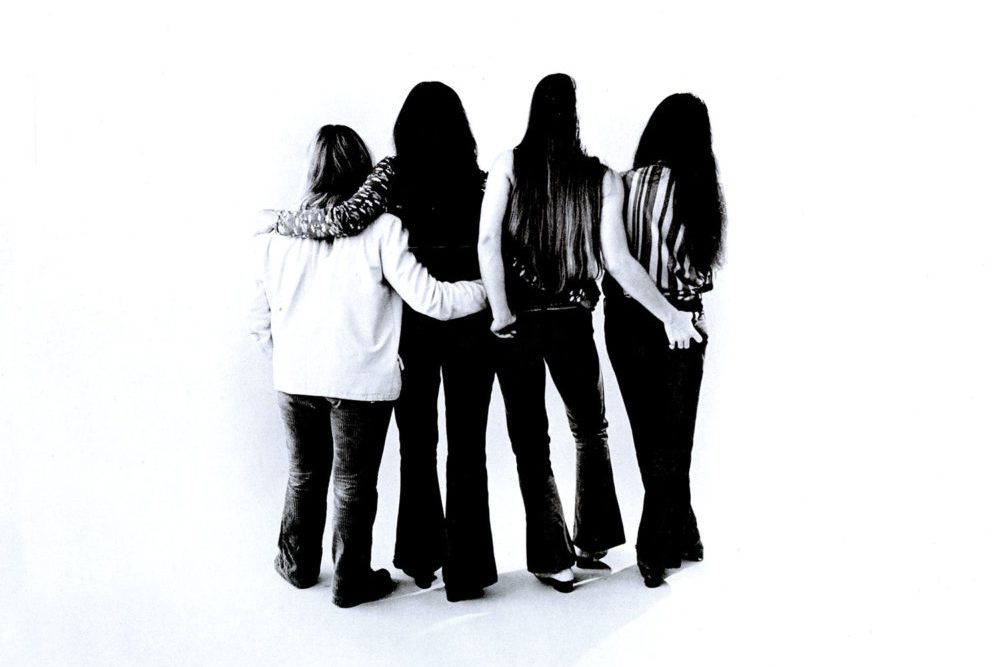

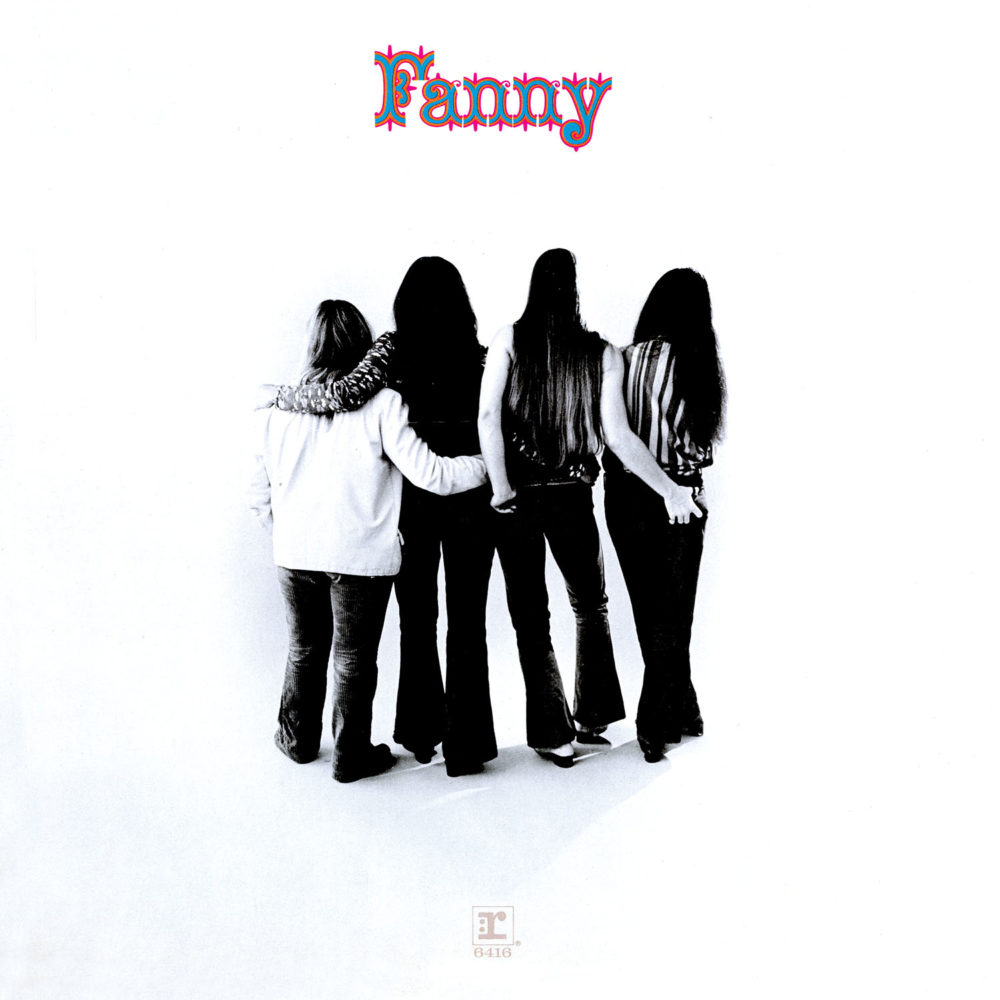

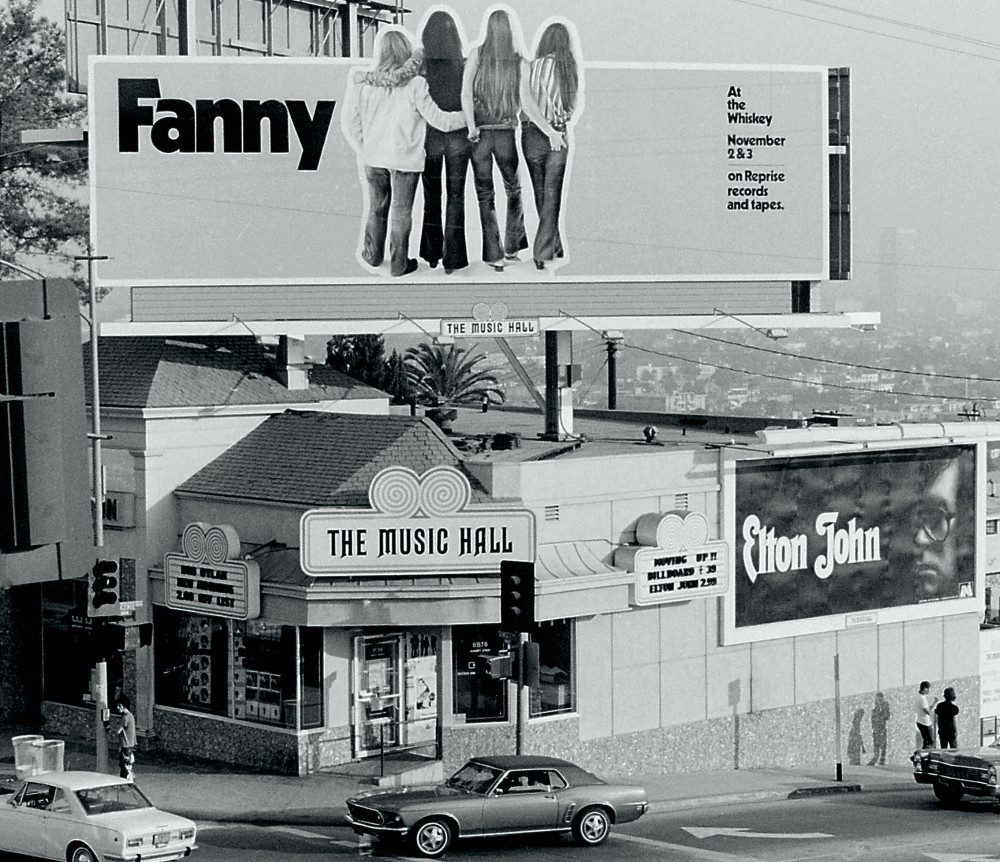

Since it isn’t a mini-series, The Right to Rock understandably condenses Fanny’s convoluted evolution. There were more lineup changes before the band signed with Reprise and renamed themselves Fanny. The film brings the excitement of this period to vivid life. When Norma Kemper, the secretary who led producer Richard Perry to the group, describes the band as “electric,” the accompanying live footage shows you exactly what captured her interest (such footage is especially crucial, as none of the band members felt their live energy was ever captured on their studio recordings).

The day-to-day life at “Fanny Hill,” the band house in Laurel Canyon, is captured in all its glory in the numerous photos shot by the band’s friend, photographer Linda Wolf. De Buhr, a self-described packrat, made her wealth of memorabilia available as well; the stickers and t-shirts she designed, posters and reviews, even her journals. It all helps make The Right to Rock a richer viewing experience.

For the first part of the ’70s, Fanny was in constant motion. “If we weren’t touring, and if we weren’t rehearsing, and if we weren’t recording, we were trying to fit in laundry and grocery shopping, because we rehearsed ten and eleven hours a day,” says de Buhr. The band always looks like they’re having a great time as they storm through a song. But offstage, it was a bit more wearying. “It was brutally tiring,” June says in the film. “To keep giving and giving and giving in that way, was unsustainable.”

And then a depressingly familiar theme comes into play. “The suits in Hollywood, who controlled the dialogue in promotion, couldn’t wrap their heads around four young women playing kick-ass rock and roll,” de Buhr contends. “They just couldn’t do it, couldn’t figure it out. Every time we turned around, there was another door we had to knock down, or another ceiling that we had to at least crack. We’d answer the same questions over and over — what’s it like to play drums as a girl? Well, since I don’t have a dick, I can’t really tell you how it’s different from being a guy. Geez already!”

Given the cultural openness of the era, de Buhr is still surprised Fanny was so underrated and mismanaged. “You’re talking about Fanny back in the day when it was all free love and hippy-dippy,” she says. “You’d think that Fanny would have been accepted more easily. But when it came down to the nuts and the bolts of who got the money, whose record was taken to radio and what DJ was given payola for what group, the politics were male-centric always. And I don’t think that that has changed.”

June was the first to leave the band, de Buhr leaving soon after (“I didn’t want to be in a band without June”). With new members, the band had a brief “glam” era before finally breaking up in 1975. After a brief turn with the Peter Ivers Band, de Buhr went into the business side of the music industry, working for a record distributor. Later, as retail marketing coordinator for A&M Records, she worked with the Go-Go’s as they promoted Beauty and the Beat, getting a gold record from the group as a thank you.

She sometimes heard her male co-workers talking about Fanny. “They’d be talking about the band just being a ‘gimmick,’ which pissed me off to no end. I didn’t say much; I didn’t let them know I’d been in Fanny,” de Buhr says. “And then I was doing an inventory at Tower Records on Sunset, and this co-worker hollered at me, ‘Hey Alice, I saw you on TV last night!’ I’m like, ‘What?’ And apparently Nick at Nite had got some of the [German TV music show] Beat-Club footage. That was back in the late ’70s, early ’80s probably. And at that point I said, you know what? What we did mattered, and I’m proud of it. And since then I’ve been trying to keep the name alive long enough to be recognized for what we created.”

The latter part of The Right to Rock focuses on the making of Fanny Walked the Earth (de Buhr made a guest appearance on “Walk the Earth”), and the unexpected health crisis that put promotional plans on hold. Footage of the group being honored at the 2018 She Rocks Awards brings Fanny’s story full circle as rock ‘n’ roll survivors acknowledged for their pioneering work, alongside testimony about their influence from such musicians as Bonnie Raitt, Joe Elliott, Kathy Valentine, Charles Neville, and Cherie Currie.

For those who discovered Fanny via clips on YouTube, Fanny: The Right to Rock fills out the rest of the story about a band of women who wanted to make a difference, and did, defying all obstacles. As de Buhr says in the film, “The conversation about women’s place is right smack dab in the middle of rock ‘n’ roll. And you’ve got this brick wall, we just start taking the bricks out from the bottom. And okay, sometimes the wall falls straight down and it doesn’t fall over. But we’ll just keep taking the bricks out.”

UPCOMING SCREENINGS:

8/6 – Two Riversides Film & Music Festival – Poland

8/13 – SAW Gallery – Ottawa, Ontario

8/15 – Jecheon Film & Music Festival – Jecheon, South Korea

8/27 – OutFest LA closing night film – Los Angeles, CA

9/12 – Musical Écran Bordeaux Rock festival – Bordeaux, France

Check fannythemovie.com for more info.