Twice a month, AudioFemme profiles artists both emerging and established, who, in this industry, must rebel against misogynist cultural mores. Through their music they express the attendant hurdles and adversities (vis-a-vis the entertainment industry and beyond) propagated by those mores. For our sixth installment, Amber Robbin profiles Weyes Blood, a one-woman psych folk powerhouse that challenges notions of waif-like femininity with hauntingly dynamic vocals, darkly emotional lyrics, and unexpectedly melodic sound effects.

Artist Profile: Weyes Blood

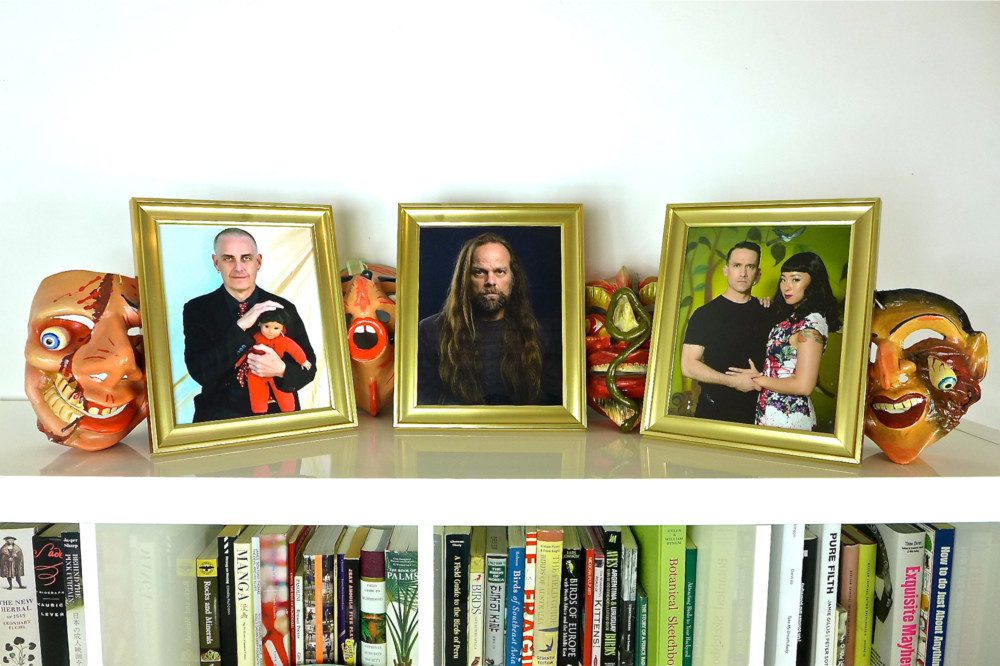

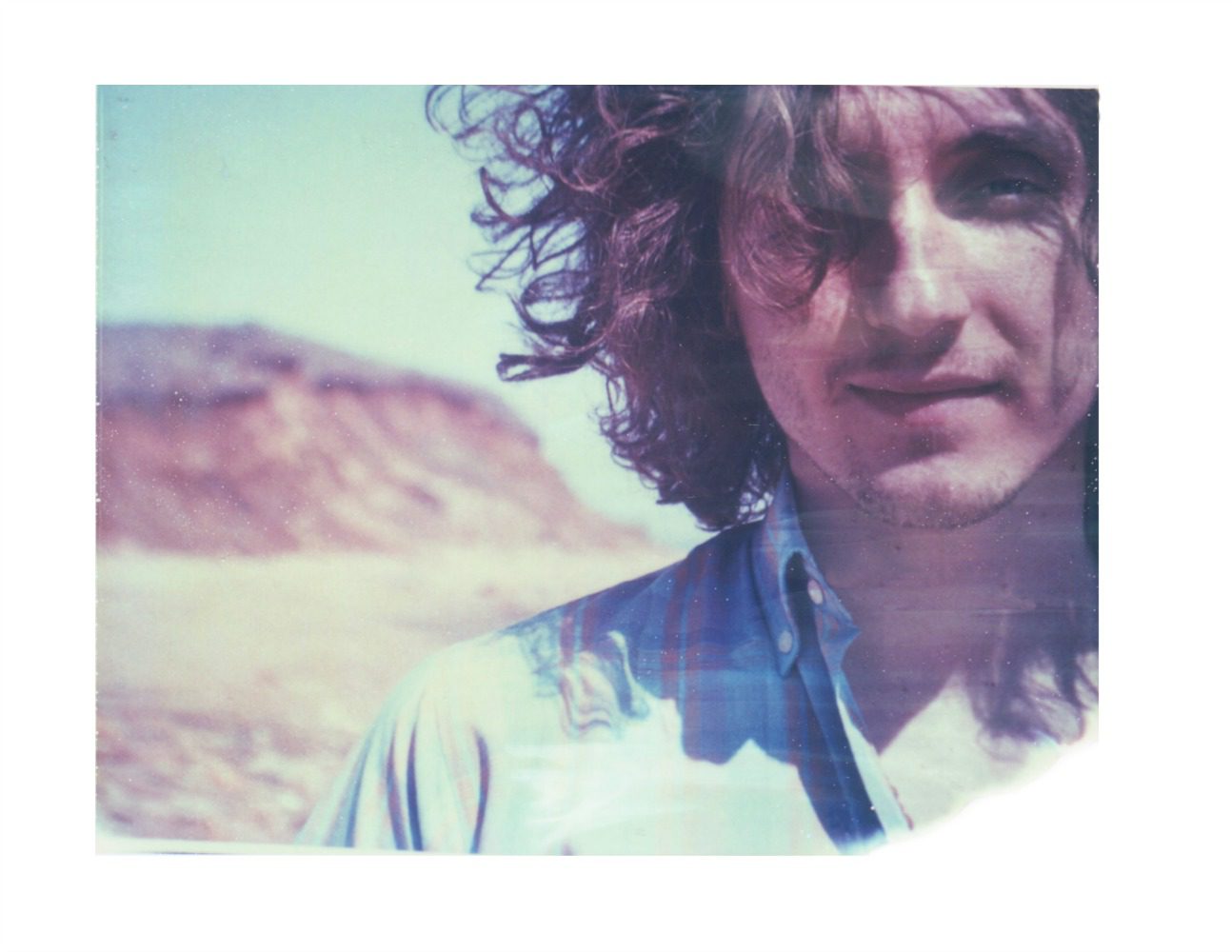

Weyes Blood is the otherworldly musical persona of folk-suffused, musique concrète-inspired artist Natalie Mering. Based in New York City with prior roots in Philly and Baltimore, Mering has previously collaborated with experimentally driven acts such as Ariel Pink and Jackie-O Motherfucker. Her second full release, The Innocents, came out on Mexican Summer October 21st, following The Outside Room, her 2011 album on Not Not Fun which was recorded, mixed, and produced by Mering herself.

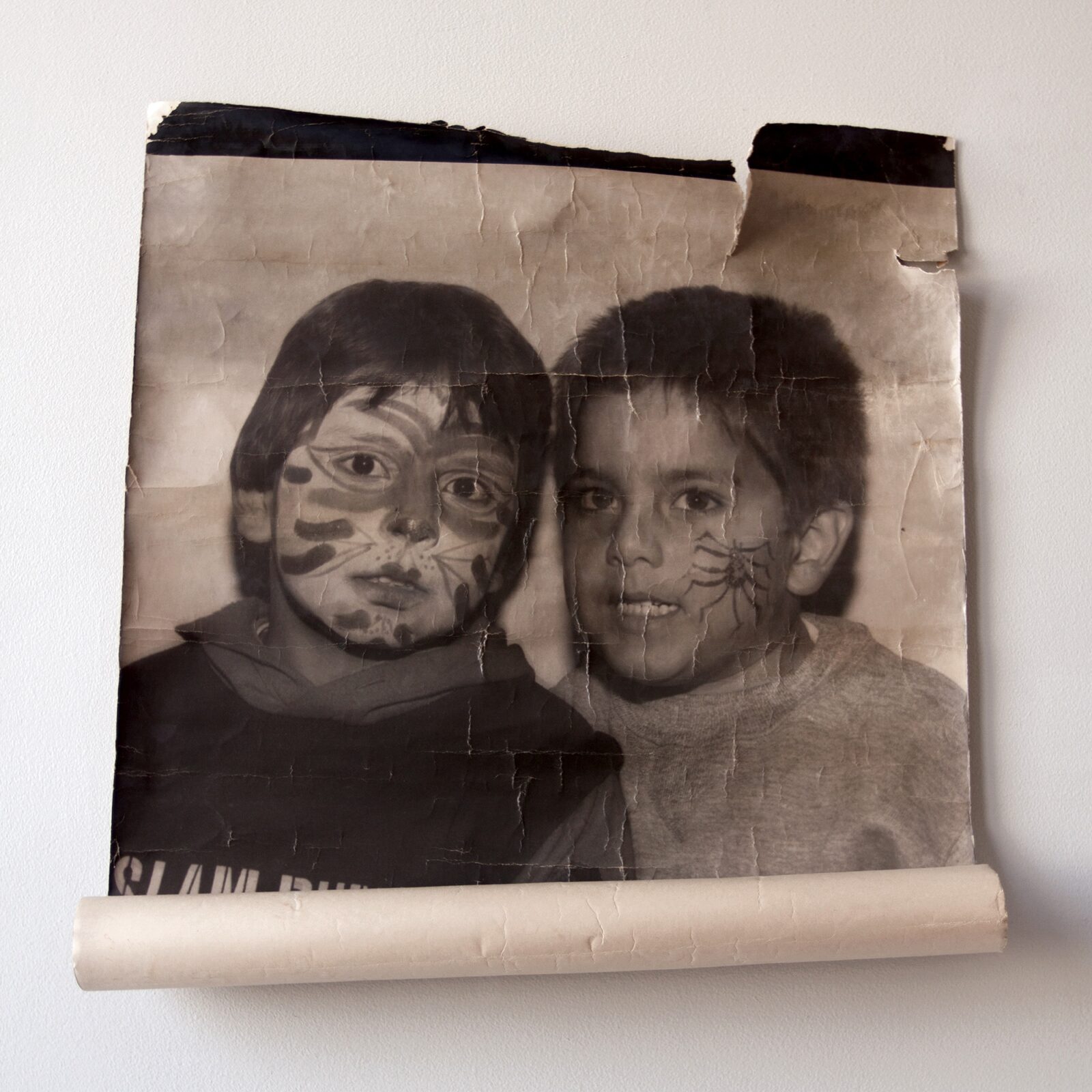

Music is in Mering’s wise blood (which, by the way, is the play on words intended by the literary-inspired pseudonym, “Weyes Blood”). Her father was a rocker in 1970s LA turned Christian parish leader, yet Mering has cultivated an aesthetic undeniably her own. Her mellifluous vocal sound is pure and ancient, driving forth compositions that are rich with artfully-chosen sound effects she seamlessly strews over traditional instrumentation. The result ranges from whimsical to profoundly heart-wrenching, with darkly psychedelic passages and hopeful glimmers of choral brilliance throughout. From the warped piano arpeggios of “Some Winters” to the acoustic simplicity of “Bad Magic,” Mering’s bereft, hovering bay unhinges the listener’s soul and carries it between intimately familiar portraits of a past life, conjuring memories that still breathe with tangible emotion.

The album is, indeed, an imprint of the past for the deep-timbred songstress. The Innocents chronicles the lost, wandering soul of an early twenties Mering and captures the distress and abandon felt by many in that age of angst and aching. Although written in the thick of her experience, Mering’s work echoes with the mature understanding of an old soul painfully aware in the midst of its own torment. She ponders her loss in “Some Winters,” the second single off the album, and faces what’s left in the aftermath of a jilted love affair…

You won’t hold me in your arms anymore

We paid our price

Lead from the soul

I’m already gone

The house of stone we built has turned into sand

and you know I’d still hold your hand

A hope I can’t conceal

A memory how we used to feel

A potential third single, “Bad Magic,” was recorded in Mering’s apartment. One of the most beloved and bare tracks, the ballad unfolds as if Mering is slowly, solemnly rallying herself yet again to face the day, despite her enduring anguish. Harboring a bursting chest and eyes forever wetted, she pushes on, for she knows instinctively that there is nowhere to go but forward. The minor melody tugs and lilts from verse to chorus without pause, like the perpetual pep talk of her heart that refuses to come up for air. It is her salvation, this inner monologue…

Make the best of death

and love what’s left

You’re not just a time bomb

Just cause you went off don’t mean you’re scattered everywhere

It’s still there

in the palms of your hand

Just give it one more chance

Don’t wait to understand

Just find a new way

Every melody is “a new way” to move forward, each chunk of poetry a new pearl to bolster her resilience. Every track of The Innocents introduces yet another approach to coping with life as we know it, cracking open our chests for the sake of remembering how we ourselves coped in the face of those most formative, and innocent, years.

Femme Unfiltered: On Natalie Mering

When I was a Broadway hopeful going to musical theatre/circus school, it became abundantly clear to me that only a few select roles were available to women. Just as in most artistic industries (see also “the world”), the options were: virgin or whore. Ok, there might have been slightly more variation, but seriously…ingénue = virgin, sassy sidekick = whore. (If you were lucky enough to have the breadth, you could also play women over 40 – the hag.) However, there was one other, lesser known category which I incessantly fit into – the dead girl. The dead girl was sometimes a ghost, sometimes an angelic symbol of love, innocence, or some other idyllic value. More a spin-off on the standard virgin with a dash of saucy see-through-ness, she served all celestial purposes of the play. She was imposing, she had sway, but she was meant to be known of, more so than seen or heard.

It was intriguing to me, therefore, when I came upon Weyes Blood and its continuously-dubbed “ethereal” front woman Natalie Mering. Mering demands to be seen and heard, and is by no means a waif beyond her waif-like appearance. Her instrument is deep and resounding, and her otherworldly musical concoctions are far too all-encompassing to garner any sort of comparison to a gaseous existence.

It hit me that Mering’s persona challenges all familiar notions of what it means to be “ethereal,” for her art is feminine, celestial, and powerful, all at the same time. Mering spoke in our interview of how all humans have an animal side, so I began to wonder if, perhaps, we all had a self-reflective, otherworldly side to us as well – one that normally lies undetected by our fumbling, animal radar. Mering extracts this element of our being and magnifies it, keeping intact all of the inherent characteristics of a flesh and blood human being: the strength, the raw emotion, the jagged edges. She uses her spiritual presence to embody the essence of her suffering, her perseverance, her enlightenment, every discovery along her epic journey, forging an otherworldly image in solidarity with the human experience. She demonstrates just how ethereal we all are when consumed by our emotions, and especially when we manage to beat the odds and, miraculously, transcend hardship.

INTERVIEW 10/17/14

I had the chance to chat with Natalie Mering aka Weyes Blood. Here is what she had to say.

AF: So Ms. Mering, how did you come to create the very specific sound of Weyes Blood? And how has your past work with Jackie-O Motherfucker and Ariel Pink informed your style?

Mering: Well, I was already making more improvisatory music when I met Jackie-O Motherfucker, and they’re more improvisatory. I don’t know how much they influenced my sound. I feel like Ariel inspired me to be more personal about my songwriting and write more from a conversational perspective. But mostly my sound is cultivated through my love of sound effects and early music, which is old church music, and trying to combine something super futuristic and also ancient.

AF: What about a musician’s personality, both as an artist and a person, makes them better suited to solo work? Why are you a solo artist?

Mering: I think it was because I couldn’t find anybody who had the same standards as I did to be in a band with. In high school and college, I always wanted to make music, but it was the ultimate, most important thing to me, and it was kind of impossible to meet anybody like that.

AF: In terms of work ethic?

Mering: Yeah, in terms of work ethic. In terms of wanting to pursue it as their career. In terms of where I was coming from artistically. It just wasn’t in the cards for me, so I just played solo.

AF: How do you feel about the word “ethereal”? Does it describe you, or just you in relation to your art?

Mering: Probably just my music. I think ethereal is a fantasy element. That, as human beings, we have ethereal elements – all of us. But we’re pretty much animals, so ethereal is kind of the escape word that we wish we could transcend to. I take it as a compliment.

AF: How did you get into music? Especially, what’s your vocal training background?

Mering: My whole family are musicians, but I was in choirs a lot in middle school and high school.

AF: Where do you get your song ideas?

Mering: Just life experiences and how insane life is.

AF: How does the creative process usually begin for you?

Mering: It’s either music or lyrics, and it’s usually kind of like a lightning flash, but it’s also very half-baked. I get little imprints of songs and melodies, and then I flesh them out by playing them over and over again. And listening. Really listening is a huge part of it. I think I have really good ears.

AF: When and how do you decide upon the unconventional sound effects you use on each track?

Mering: I guess in any atonal sound there’s usually a melody, even though it is atonal, that will kind of sync up and match with the melody of the song. So, it’s almost like pairing…it’s kind of like a wine pairing. (Laughs.) Like some things go better with other things. It’s not all totally random. And once again, listening is the biggest thing. Listening to its relationship to the song and deciding if it adds to the song and brings it more life, or if it’s distracting to the song and takes away from it. Because with sound effects it’s pretty black and white.

AF: Do you find that you face discrimination and adversity within the music industry as a female?

Mering: Yeah.

AF: Do you consider yourself a feminist? What is your definition of feminism?

Mering: I am a feminist. The definition of feminist is to want equal opportunities and rights for women, paying women the same amount, etc. etc. But really what happens in music, is music is really just a big cult of the personality anyway. So, like a male personality is usually more appealing to everybody on a marketing level or an excitement/popularity level. I feel like women have to get in there and make incredible music to get the same amount of attention while a man could make music that’s more based on having a crazy personality, being a kooky guy, and everybody loves it. I think that that is what attracts a lot of people.

I don’t know, it’s also more difficult for men because it’s a little easier to be more singular as a female. So I wouldn’t say it’s totally this terrible thing being a woman in music. It can work to your benefit also. I just find that in terms of the people that I have worked with, it’s easier to get pigeon-holed as “mellow chick music” even though I think I can bring a lot of intensity and excitement. I think that’s happening less and less as more women are doing solo music than ever before, but some people just hear a female voice and that’s the first thing they think.

AF: What do you find to be the most challenging aspect of your work?

Mering: Probably hearing something in my head and then trying to make it a reality, in real life, only to find that it always comes a little short of the fantasy.

AF: What’s the most rewarding aspect?

Mering: Getting to connect with people and make people feel that living is worthwhile via creation and art. I think that’s a very elating experience.

AF: In multiple interviews, you talk about The Innocents being about disillusionment and innocence ending in a person’s early 20s, and how once this album was recorded, you realized you’d already grown past that theme. What themes are you exploring now?

Mering: I don’t know, probably ones that are just more existential. Things beside heartbreak.

AF: What’s beyond heartbreak?

Mering: I don’t know. Like not having a heart anymore and trying to figure that out. (Laughs.)

AF: That’s dark! Alright!

Mering: I mean, it’s existential, it’s dark, but there’s also a lot of lightness – I’ve been writing some happy songs too.

AF: So what’s next for Natalie Mering and Weyes Blood?

Mering: The album comes out next week and then I’m gonna do some heavy touring. I put together a backup band, so still kind of solo, but also with a full band. I’m gonna record my next album next year and just get cookin’ because time is flying and things are changing, and the new set of songs that I wrote are already getting old. Which is one problem with the music world. Creativity kind of comes so fast and albums are these laborious, long events. I look forward to recording the next album. That’s what’s next for me.