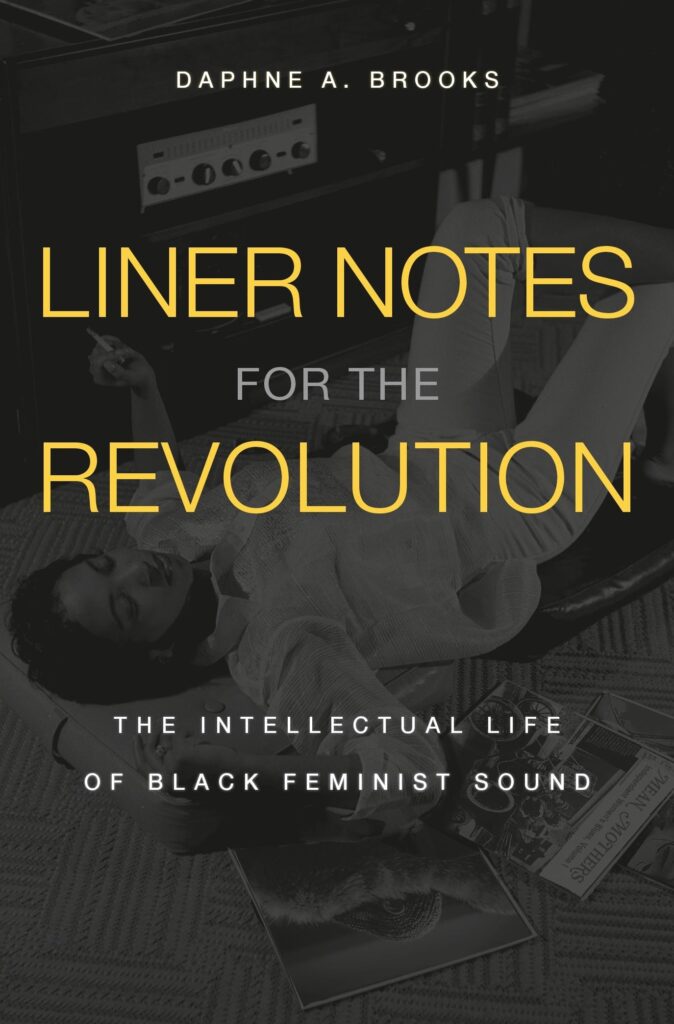

“Sometimes, it feels like I’ve been writing this book all my life,” says Daphne A. Brooks, author of the recently released Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound. Brooks, a Yale professor who previously wrote Bodies in Dissent and the 33 1/3 book on Jeff Buckley’s album Grace, grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1970s and 1980s, where she developed an affinity for both rock music criticism and Black feminist literature. “I’m a Black Gen Xer who was bequeathed this landscape of post Civil Rights integrationist culture, at least, on the one hand,” she explains, “even if that’s accompanied by racial retrenchment politics of the Reagan/Bush era and beyond.”

In Liner Notes, Brooks, who herself has penned liner notes for releases of music by Aretha Franklin, Tammi Terrell and Prince, fuses her intellectual passions to take readers deep into library vaults on an exploration of the legacy and impact of Black women in music. This isn’t a traditional music history book, although, at one point, Brooks had considered writing “a long, sweeping history of Black women and popular music culture.” Instead, she says, “the book that I ended up writing is really about the story of why we’ve never had a book like that before.”

Divided into two sections (fittingly, “Side A” and “Side B”), Liner Notes crisscrosses through time as Brooks connects writer and singer Pauline Hopkins, who was active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Janelle Monáe; looks at famed author Zora Neale Hurston’s work as a singer; and digs into the the quest for music and information surrounding 1930s blues musicians Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas.

It’s a book that’s as much about the music as it is about the efforts to uncover and preserve the legacies of the artists. “I’m an archive freak,” says Brooks. She spent years traveling to and digging through material at Rutgers University’s Institute of Jazz Studies, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem and Harvard’s Schlesinger Library. “I love spending time in archives, because of the ways in which you can really handle the materials of other individuals rooted in history and see what they left behind for us,” she explains.

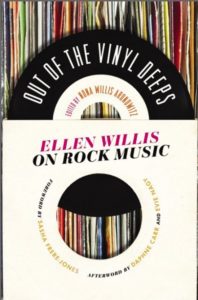

One of the archives she visited early in the course of this project was that of late journalist Ellen Willis, who was The New Yorker‘s first pop music critic. Here, she made an interesting discovery. “What I found in [Willis’] archives is that, when she was an undergrad at Barnard, she had interviewed Lorraine Hansberry as being someone who was influential to her,” says Brooks, “which was intriguing because Ellen Willis was this badass radical feminist but she didn’t write very much about race and about Black music once she became a music critic.”

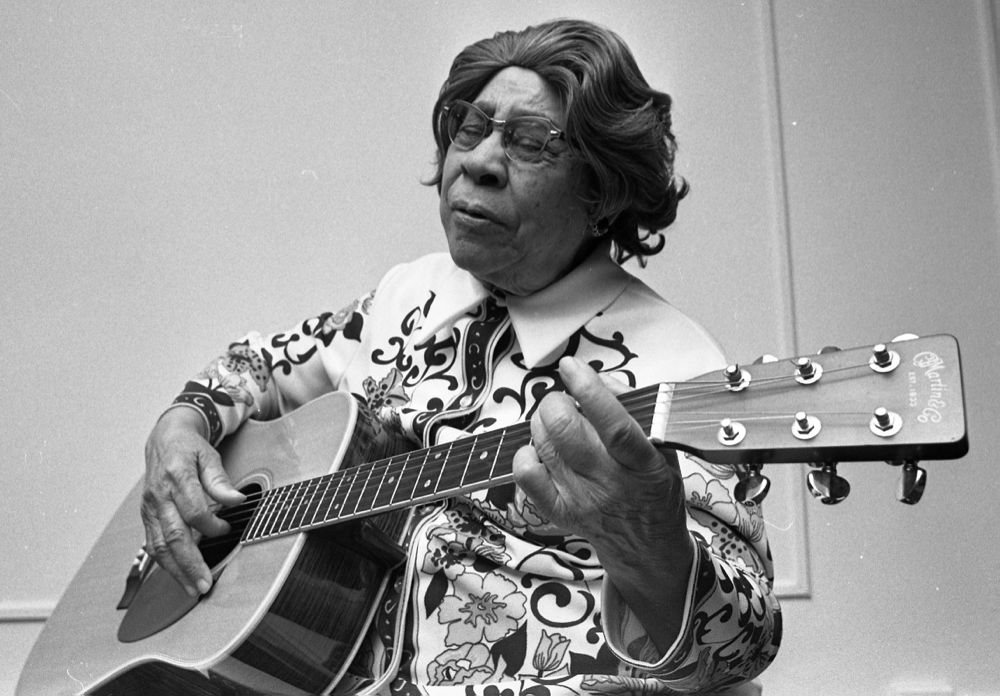

Brooks also delved into the archives of Rosetta Reitz – 67 boxes of notes and writings in the care of Duke University – in her research as well. Like Willis, Reitz was a Jewish feminist based in New York. She launched Rosetta Records in the late 1970s to reissue hard-to-find recordings from women jazz and blues musicians. “She also wrote her own liner notes, her own kind of critical essays, to accompany these recordings, in which she just laid down this hardcore radical feminist second wave prose that was absolutely gorgeous about why we needed to really regard the blues women as being these absolute pathbreaking sonic innovators,” Brooks explains.

Liner Notes highlights the intellectual labor involved in making music, as well as the labor attached to preserving the art and artists’ life stories for future generations. In reading the book, you might wonder, how important is it for artists and thinkers to maintain archives of their work? “I think it’s crucial with regards to being able to care for the historical work that they’re doing, in part because we are given access to the richness and the depths of their creative life-worlds and their intellectual life-worlds,” says Brooks. If an artist does leave behind an archive, she says, “those materials allow us then to continue to extrapolate the different kinds of stories we might tell about why they matter to us.”

However, not all artists leave archives and that can be for a number of reasons. “That is also an ethical kind of phenomenon in and of itself as well, if they choose not to or if they don’t have access to doing that,” says Brooks, “which we know is true of all sorts of marginalized women. Women of color, African American women and Jim Crow American culture didn’t have the kinds of formal ways of documenting the historicity of their own importance.” But, there were informal methods and that leads to various ways that future generations might engage with the work, which is also part of Brooks’ book.

As to whether or not contemporary artists are considering future archives, Brooks says that’s a complex subject. “It’s been complicated with pop musicians, especially African American ones too,” she says. “Historically, we have been so deeply disenfranchised, not only in the context of this country but also the recording industry and the kinds of reparations that have yet to be paid to them. So it means that you have generations of Black artists who have been wary of where and how their material archival life-worlds are handled.”

Meanwhile, though, she says she would love to know if someone like Solange, who Brooks interviewed as part of a David Bowie and Prince conference that she organized at Yale in 2017, is considering archiving her work. Brooks describes Solange as a “robust intellectual force” whose reading informs her art. An example that Brooks mentions is the influence that Claudia Rankine’s 2014 book Citizen had on Solange’s widely acclaimed 2016 album, A Seat at the Table. “You want to have her archive all the notes,” says Brooks. “You want to see her copy of Citizen and how it’s marked up and what are the drafts of different tracks, from ‘Cranes in the Sky’ to ‘Don’t Touch My Hair,’ that have some kind of a through line between Rankine’s poetry and the songs that end up on the album.”

Says Brooks, “That’s partly what I’m talking about, what’s important about the archives, but also what I dream of what a Solange archive might look like.”