When I arrived in Mexico for my first three ayahuasca ceremonies, I had a checklist of questions to address: What repressed childhood memories were shaping who I was? Why did I hate my mother so much? Could I stop lying? What was wrong with lying if I didn’t get caught? So, I was surprised that after my first sip sunk in, the face to appear in my mind’s eye belonged not to my partner or my mother or my father but Dutch, the publicist for Houston’s Day for Night music and art festival. And accompanying his image was the message: Receive love and you’ll learn to give it.

Three months prior, I broke it to Dutch that after two years of covering Day for Night, I’d have to miss it. My ayahuasca retreat overlapped with the first two days. But he wouldn’t take “no” for an answer. He said he’d convince the shamans to hold a special, non-overlapping retreat just for me. He asked for the website so he could contact them. He was actually serious.

His idea was absurd, but it was also full of love. Love I couldn’t feel. I could only feel guilt for not coming. Yet another obligation. I hated being tied to others.

A few weeks later, he apologized for making me feel guilty. It wasn’t about the press coverage — he just wanted to see me. So, I asked if he could fly me there even if I missed the first half. He pulled some strings and got me credentialed. And when I didn’t like the flights he proposed, he pulled more strings and got different ones. I’d come in time for the second night, stay for the third day and a few extra days, then fly to Boston to make a meeting.

They say ayahuasca stays in your system for as long as you follow the “dieta,” a sugar-free, salt-free, alcohol-free, dairy-free, caffeine-free diet aimed at bringing out the medicine’s effects. But I wouldn’t know. The moment I got off the water taxi from the retreat, I ordered an iced cappuccino with extra milk. Fuck the dieta, I thought. Fuck rules.

Yet I swear that as I flew to Houston, the insights kept streaming. “Dutch, you’ve done it again,” I thought as I entered my five-star hotel room. The love in his actions sunk in. Maybe being tied to others wasn’t so bad.

I barely felt the ayahuasca my first two ceremonies. The shamans kept me at a lower dose than others; it was their intuition. During the third ceremony, I got fed up with feeling nothing, and in the dark, when the shaman offering seconds (to everyone but me) said “who’s this?” I said the name of the woman next to me.

This time, I felt it, and my body came alive. I realized how dead I’d been, how checked out. My goal from then on: to check in to life.

After that, the people on the retreat told me I was looking them in the eye for the first time. I had no idea I wasn’t before. But as I walked through Day for Night’s festival grounds, it became clear something had changed. I was holding people’s gazes. I wasn’t spacing out.

One man who met my eyes followed me to the art installations upstairs. “I just had to say I think you’re gorgeous,” he said. I was careful not to mention my boyfriend as we flirted and left the festival for a drink. As it turns out, ayahuasca is not a magic potion that cleans up your behavior.

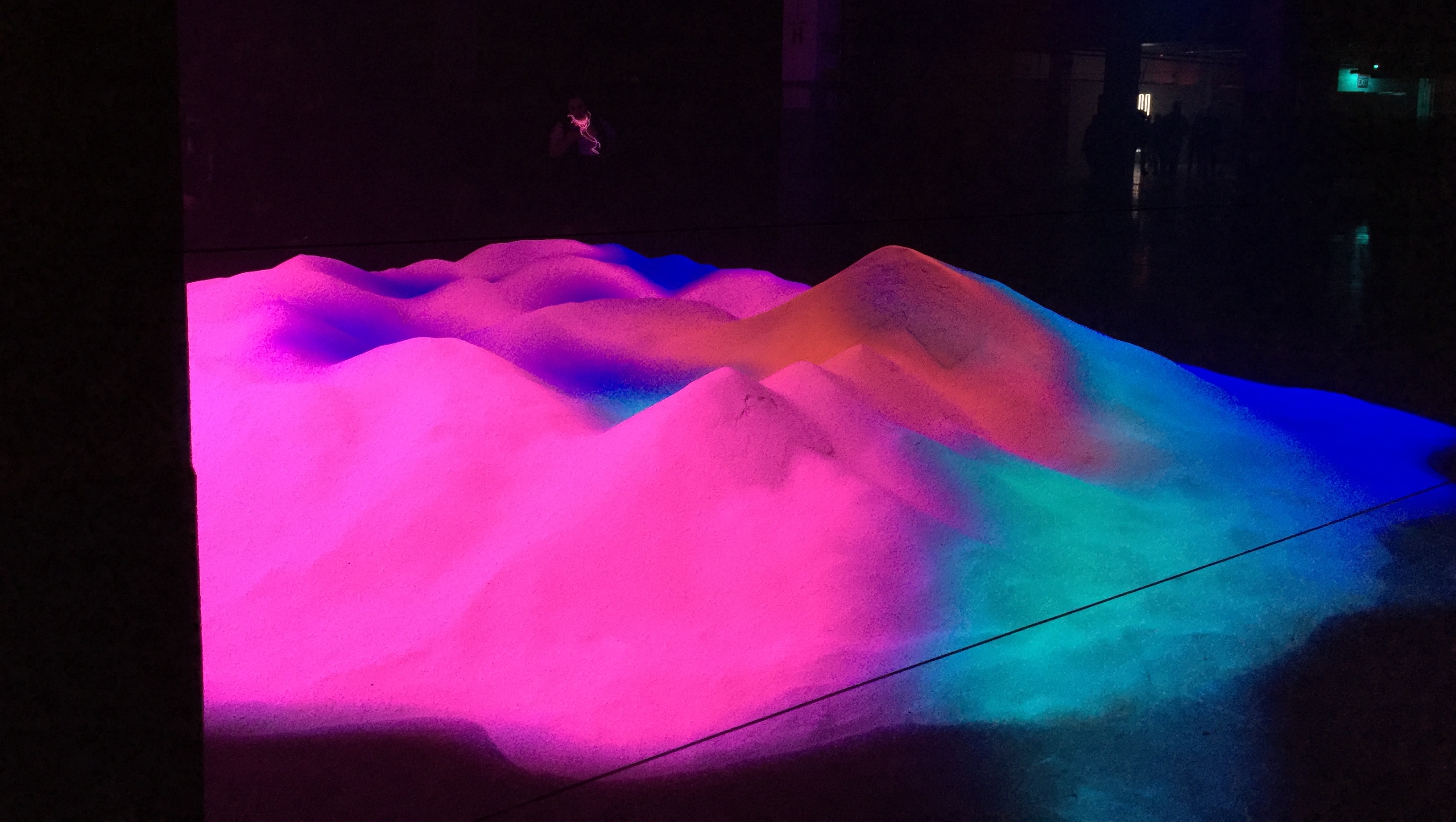

The irony of doing what you love for work is that once it becomes work, you start to love it less. In 2015, Day for Night became the first music festival I covered. Wandering its six acres of art installations, I felt like a child in a funhouse. But then, festivals became exhausting. An obligation.

Despite reaching for a new, hyper-connected way of being, I felt numb to the festival’s excitement. I tried checking in to The Album Leaf’s show. I heard drums and a guitar and a violin, but still no emotion. Thoughts like “You should see Solange; she’s Beyonce’s sister” filled my head. I keenly felt the joylessness in these statements. I remembered why I’d begun taking MDMA at festivals.

If you want to recover your lost joy, take MDMA. If you want to discover how you lost it, take ayahuasca.

A man from LA was selling CBD gummy bears and chocolates, and I bought a package of each, hoping they’d help me sleep. Five minutes later, he found me by a circle of white, sound-producing screens, where he pulled me in for a kiss. I pushed him away. “I thought you were giving me ‘I want you’ eyes,” he said. This is the risk of looking, of being seen.

I retreated to my hotel for a nap as the CBD kicked in, and on my way back to the festival, three guys invited me for drinks. As I sipped my first, I told them the story of how I got ayahuasca by pretending to be someone else. Midway through my second, I told them I had a boyfriend. If ayahuasca won’t bring out the truth, alcohol will.

They didn’t care. “I bet you look good naked,” one said as he looked me up and down.

“I’m not wearing underwear,” I replied. “Fuck underwear.” Fuck rules.

We parted ways before he could confirm this, but later that night, I met up with the man from the first day, and we went back to my hotel. A few minutes into a forced-feeling hookup, I realized I didn’t know why we were there. I wasn’t attracted to him. After shoeing him out, it hit me that despite all the eye contact I’d made, I felt just as disconnected as before. I was having my cake and eating it too, but I was eating it alone in the dark.

Then came the answer to a question I’d asked ayahuasca days before: The problem with lying is that nobody gets to know who you really are. And whether we’re vomiting our guts out in the Mexican jungle or peeking through strobe lights to meet everyone’s eyes at a festival, all we’re really seeking is to be seen.

Two days later, I met Dutch for a drink on a bar porch in Montrose. I told him about lying to get ayahuasca, about hooking up with people I don’t even like. “I don’t know why I do it,” I said, eyes darting down at the table.

“Because you’re a homo sapien,” he replied.

I may not be ready for the world to bear witness to my truth, but at least I have friends who can bear witness to my lies. I soak in the love in this witnessing, so that maybe one day, I can be my own witness.