ONLY NOISE: David Bowie’s Death Revived My Inner Rebel

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Phoebe Smolin recalls how justifying tears for an idol she’d never known helped her end an abusive relationship.

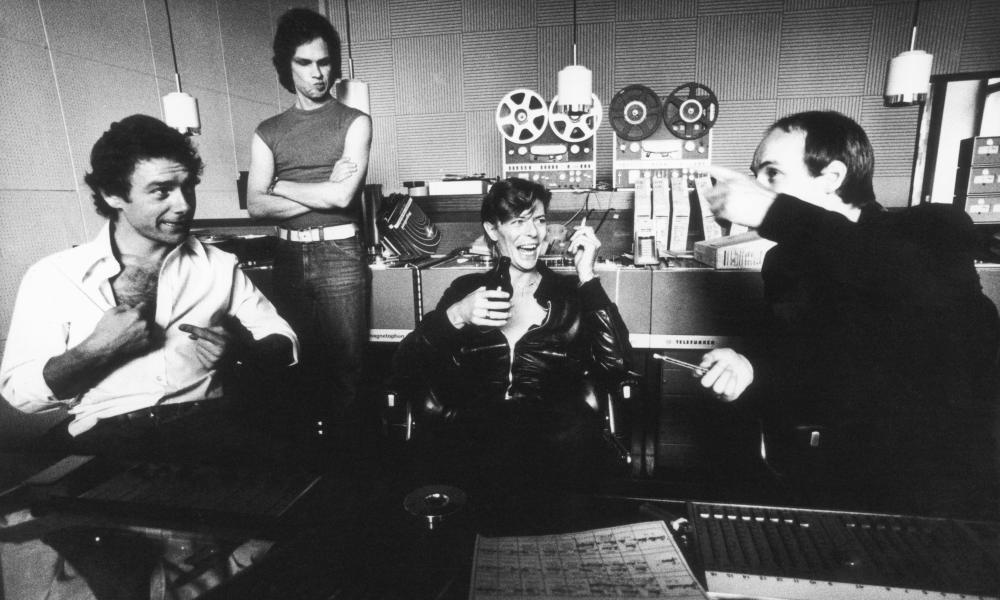

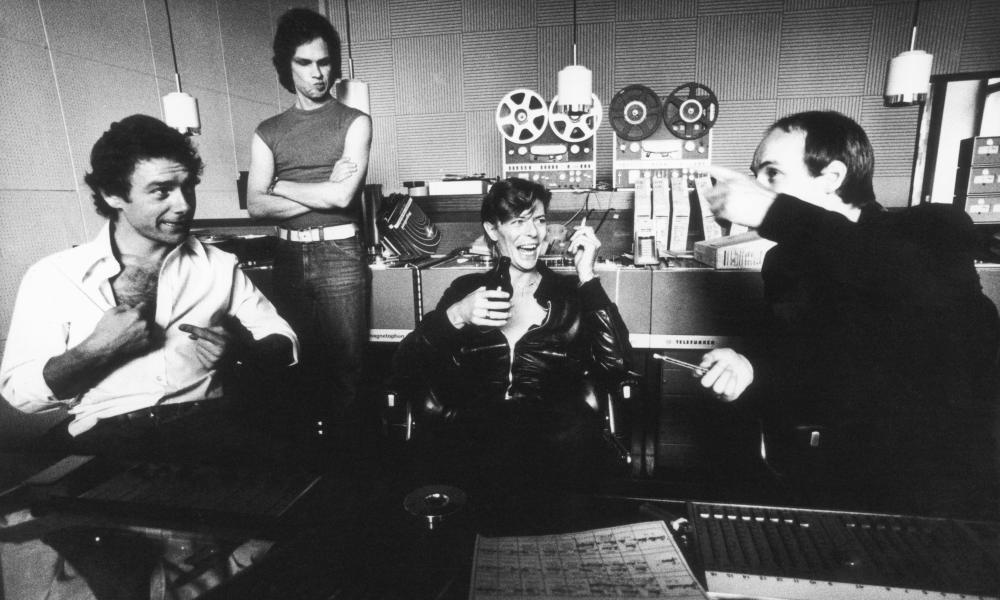

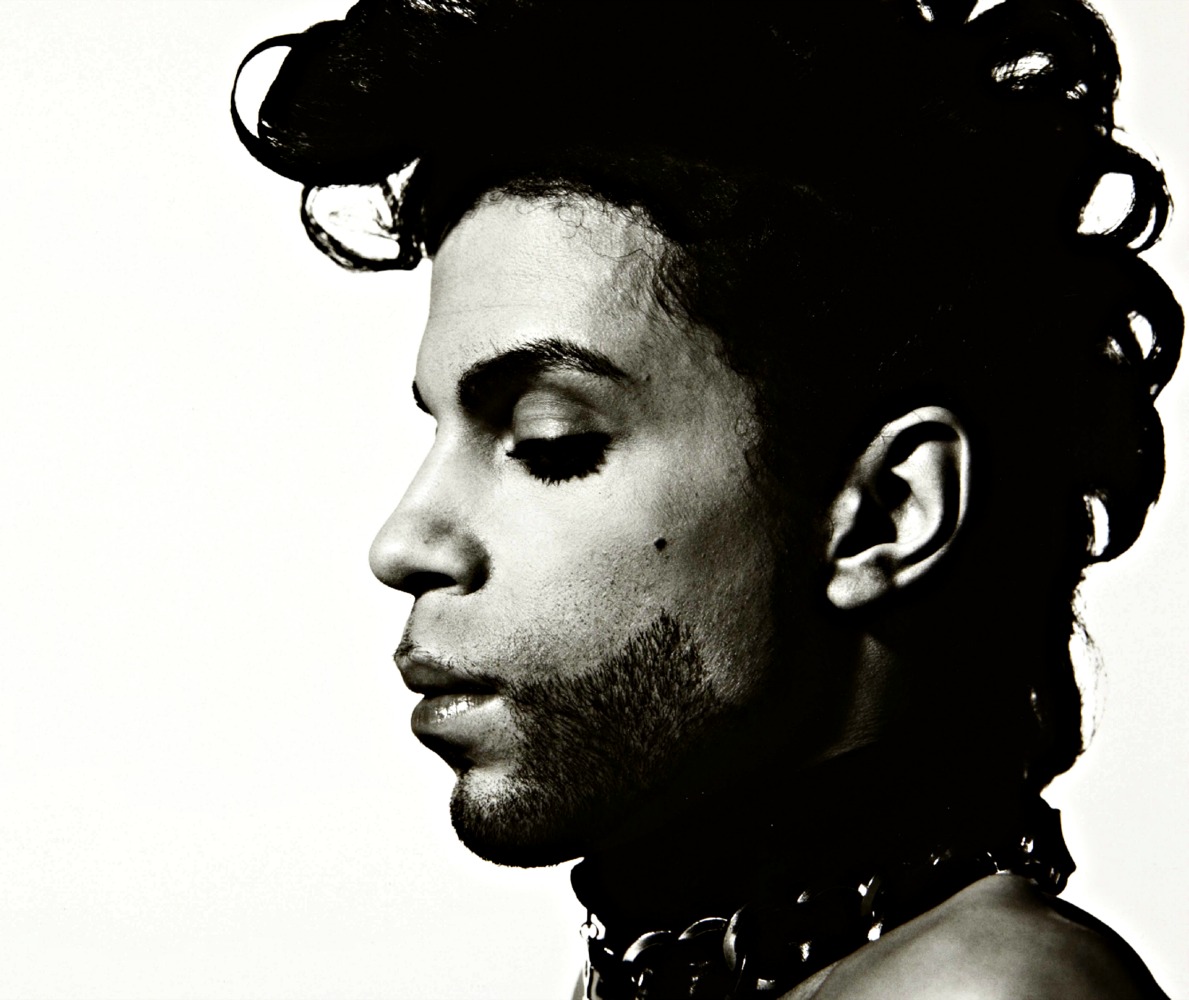

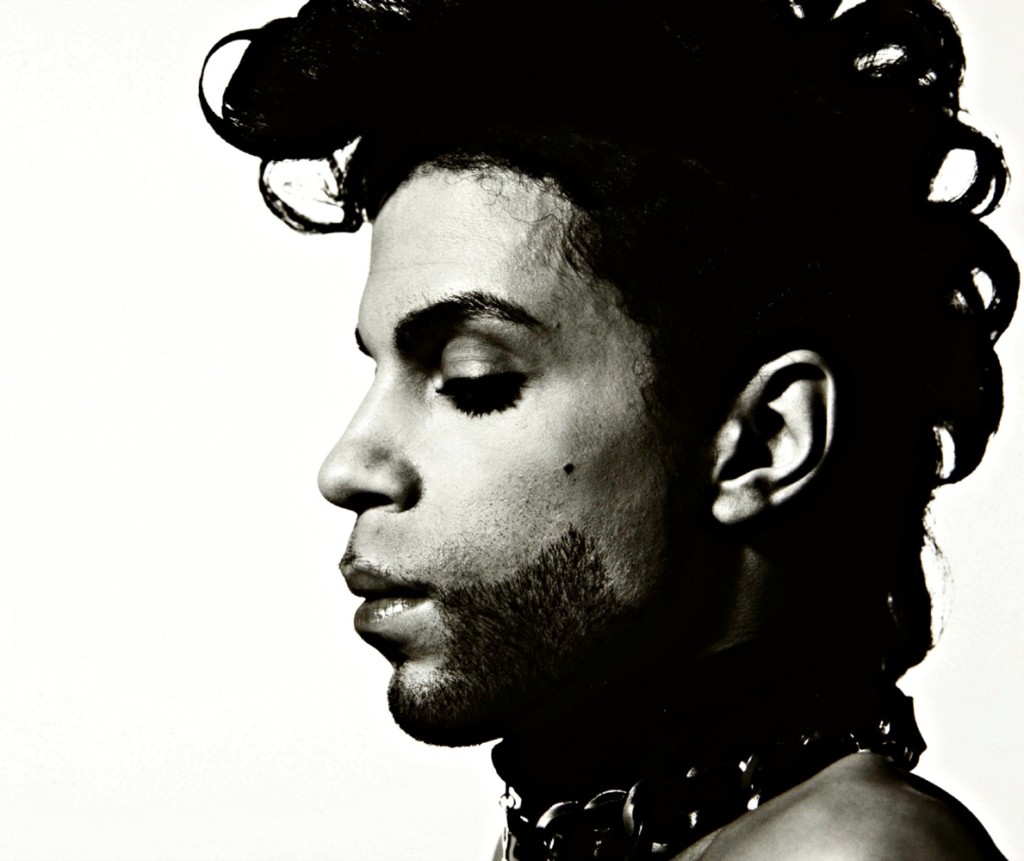

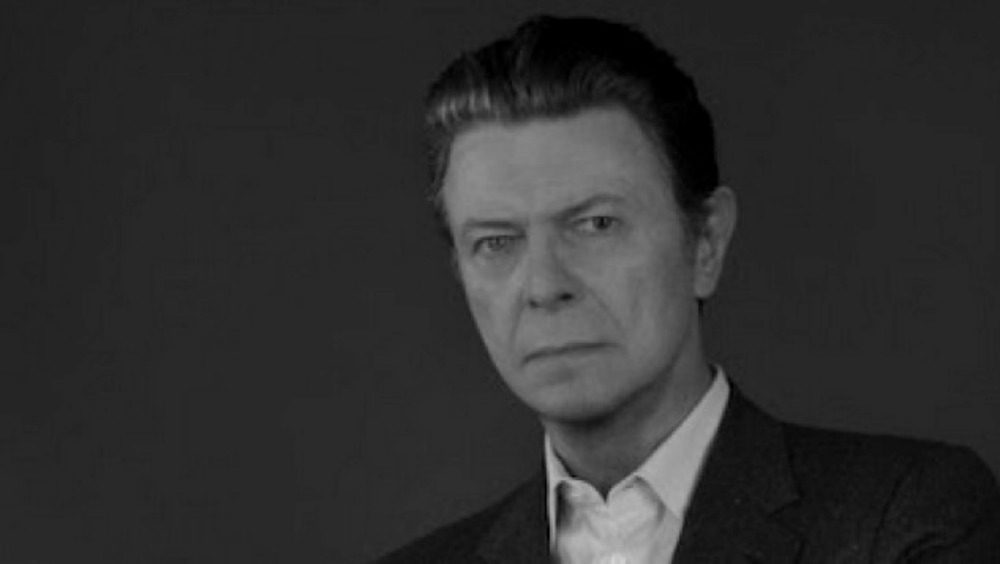

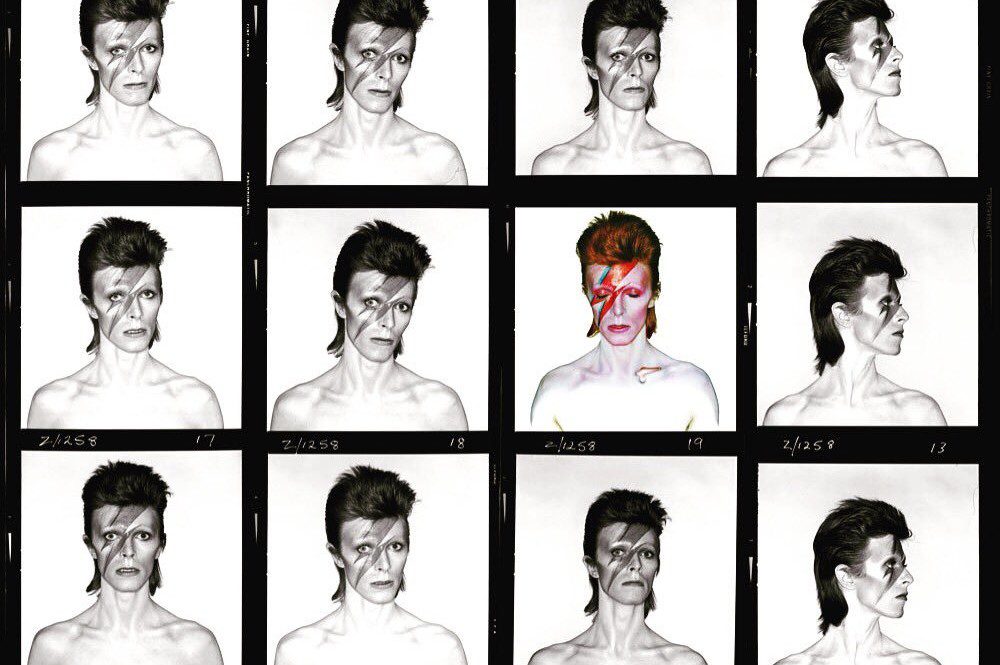

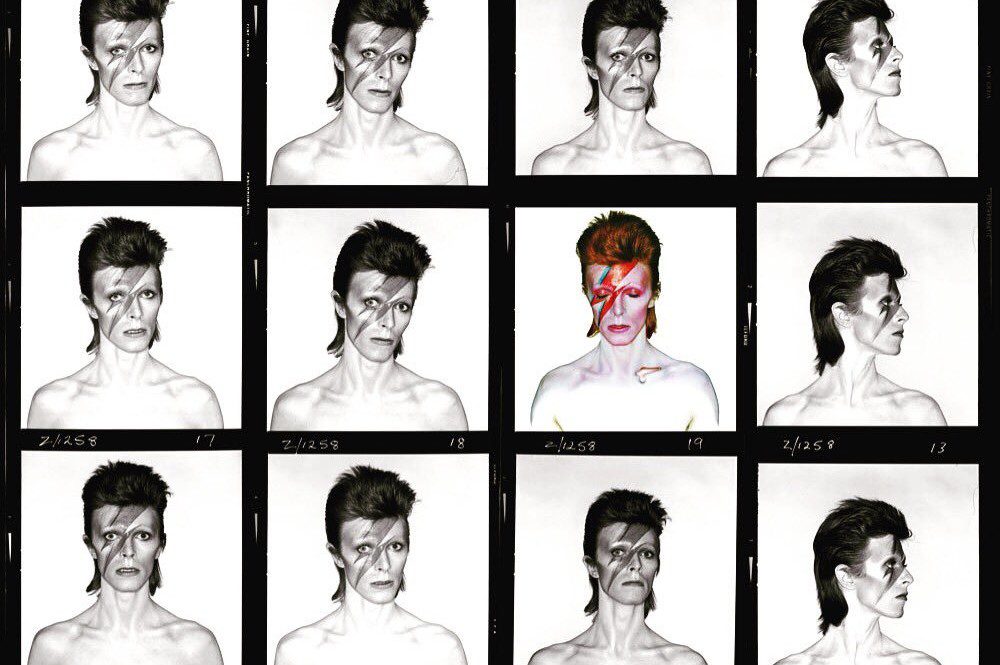

David Bowie was, at age 12, the first person (Starman? Twisted angel? Rock and Roll Fairy Dust Creature?) who taught me how to hang onto myself. Growing up a strange cross between a hippie and a punk kid in Los Angeles, at the intersection of worlds that were often in conflict with each other, Bowie’s glittery shamelessness became my unrelenting ally. As I navigated how to jump through the fiery hoops that came with being a weird kid in a city with teeth, he was there, singing me along. When I started guitar lessons at 13, I spent a year learning how to play the entire Ziggy Stardust album. “Changes” was the first song I ever played in front of an audience. “Oh You Pretty Things” was my alarm clock for all of high school, holding my hand when I didn’t want to face any other kind of music. “Rebel Rebel” and its life-giving melody got me on my feet after I got rejected from 11 colleges on the same day and eventually decided to move back east to study Ethnomusicology at the only school that accepted me (it was amazing). Pin Ups was on a loop when I moved to Chile during college. Diamond Dogs kept me joyful when my first label job revealed the evils of the music industry all too quickly. And my warped vinyl of Aladdin Sane was there the night he died, spinning as I cried into my wine glass, hollering love has left you dreamless into the mirror at a 25-year-old girl who didn’t yet understand how far away from herself she’d grown.

For three years I had been living in the palm of a Monster’s hand – a person who ate my love for breakfast. His name was Dylan.* It probably still is. On January 10, 2016, I had already grown used to waking up in tears next to someone who forced me to the edge of the bed, I’d learned to dig for the affection in every ‘you’re incompetent’ and ‘shut up,’ I’d stopped playing music because he told me I couldn’t, I’d thrown my go-go boots away. All of the weirdness that defined and guided me (and that Bowie taught me was okay) was tucked away, and my defenses had taught me to redefine pain as love. It seems severe, but, as I later learned (thank you, therapy), a standard part of this cycle makes all of that severity feel very normal.

The day Bowie died was the first genuinely beautiful day I’d had in a long time. Dylan had gone back to his home country (though kept me at a close grip despite the ocean between us) and I did something that he would have hated: spent the day with two of his friends (who were, of course, also mine, but only when I had permission). For hours on end these boys and I ran around Disneyland sneaking joints behind roller coasters, blissfully staring at exaggerated notions of America’s imagination, having laugh attacks on the Indiana Jones ride, perfectly soft pretzels, and periodic group hugs that felt as if we were hanging on for dear life. It was the first day we had alone without him. We were allowed to love each other openly, finally. I had no idea our last hug that day would be a goodbye that would last years. I had no idea that moments later my heart would be broken. I had no idea that hours later, I’d realize it’d been broken for much longer.

I was on the 405 smiling (a rare occurrence on the 405), giddy from the day’s adventures. My phone was dead, and I turned on the radio to facilitate a traffic dance party as I drove toward the tacos I was craving. Instead, I heard one minute of a song before KCRW’s Dan Wilcox interrupted it with tears in his throat: “I… I don’t know how to tell you this- but David Bowie has died.”

I felt my hands shake, swatted at the stars in my eyes, and pulled to the shoulder because the mere act of driving stopped making sense. Mortality is never clearer than when you’re on the 405 between Anaheim and Los Angeles beginning to process the death of someone you forgot was human. I sat there, flipping through the stations hoping it wasn’t real. It was. Starman was gone.

I pulled myself together and raced home, stumbled into my apartment, and put on the Aladdin Sane vinyl that I shamefully hadn’t listened to in ages, cracked a bottle of cheap Trader Joe’s red wine, slipped on a glittery jumpsuit, lathered on lipstick, and threw a farewell party.

After calling my mom, I called Dylan. At that point, I didn’t yet understand that he was a monster; I loved him, deeply. He was my – well, I never really knew what to call him. He’d repeatedly tell me he’d ‘never be my boyfriend’ – usually when I tried to grab his hand in the car or kiss him in public. We showed all the signs of a relationship – we slept in the same bed nearly every night, he hated the thought of me with anyone else, I made dinners after work and we went to movies. I was his when he wanted me. But he was never actually mine.

I felt like I needed to call him, because if he loved me like I’d always wanted him to, he’d understand that my world had just been shattered. At that point it had been nearly three years of that blurry hopefulness – maybe this time would be different, maybe this time he’d see me.

It was the early morning where he was and I woke him up. “Hello?” he answered with that morning voice everyone knows.

“Sorry to call so early I just needed to talk to you about something,” I blurted.

“Ok, what?” he asked, emotionless.

“David Bowie died. I can’t really believe it.” I said, still teary-eyed.

There was a long silence before he responded, “This isn’t about you. I can’t believe you’re making this about you. How could you be so selfish? You didn’t even know him. You disgust me.”

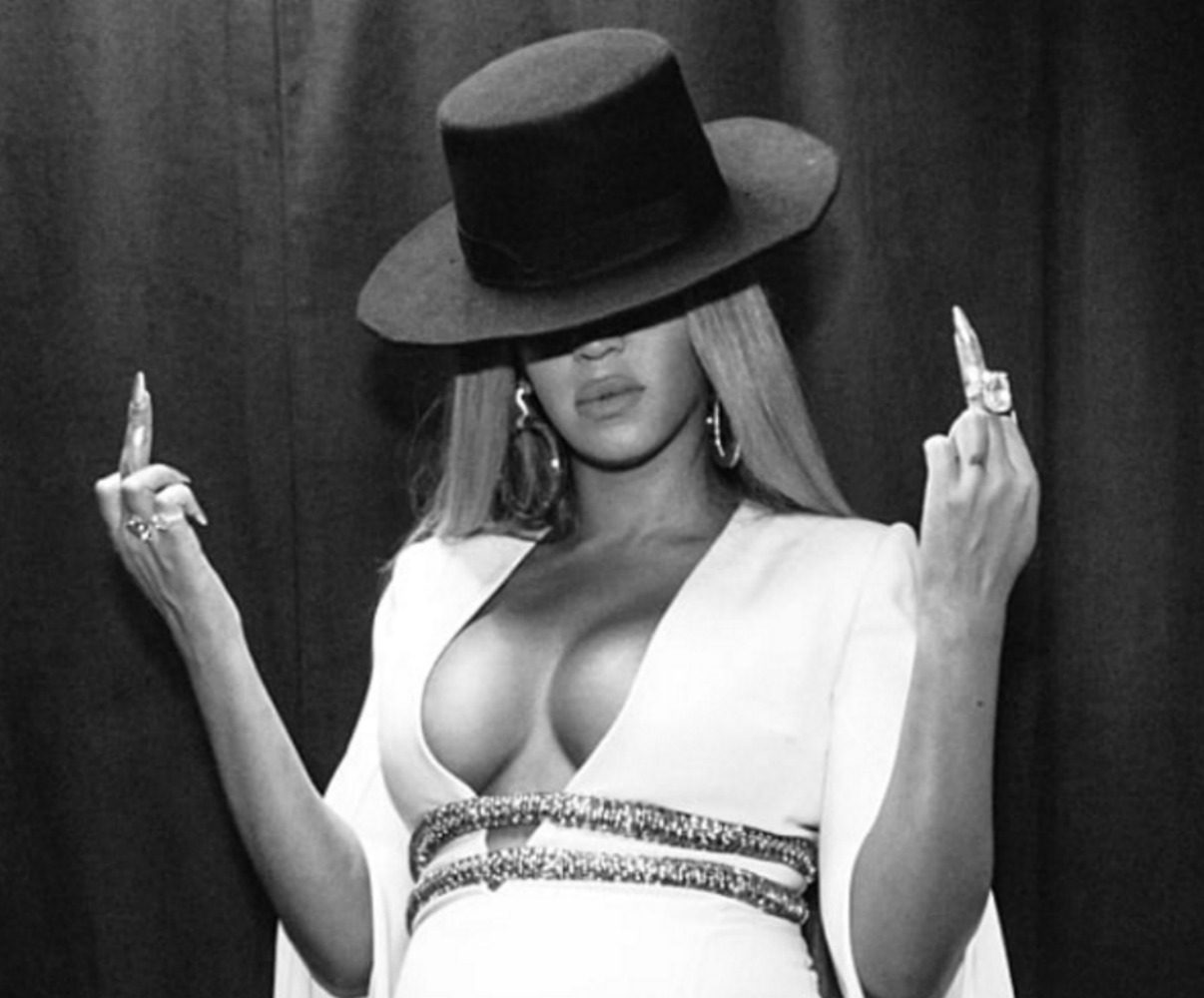

My immediate reaction to the last three years of that was always to say “You’re right, what was I thinking? I’m an idiot.” But this time I hung up the phone (still in tears), saying nothing, and let my head spin as it needed to. I felt angry for the first time in years; how dare he? With no doubt in my mind, I flipped the record and started writing. This IS about me. This is about songs that have held me and healed me through my entire life, a person whose art made me feel less alone, a starman who told me that weird was okay – that it was essential. I never knew Bowie. I always knew Bowie. He somehow knew me, in a way that Dylan never would.

I wrote furiously on my apartment floor and, as I was beginning the grieving process for this glittery hero of mine, I also began another sort of grieving process. A spell began to break. I remembered my first kiss with Dylan, which wasn’t romantic. It was at my best friend’s birthday party, very quick, and ended with him scolding me for not having done it sooner and promptly leaving and walking a dramatic mile back to his downtown apartment – something he never let me forget. I remembered the first night we spent together, in a fort my roommate and I built in the living room. and how the first thing he said the next day was “That could have been so much better.” I remembered the ways he criticized my work and eventually convinced me to stay home from certain professional gatherings because there supposedly was no point in me being there. I remembered how he made me sneak out of his apartment when his brother was visiting so his family wouldn’t realize I existed. I remembered the girl in New York who he kissed while looking me in the eye. I remembered how he called me stupid. I remember feeling like a distraction and adapting to being hidden. I remembered how I cried every day. I remembered having to fight for eye contact and intimacy. I remembered that one time he started yelling when we tried to play guitar together because I messed up the chords. I felt the weight of being a secret for three years. I felt my bruises. I understood in that moment it had never been right. That this wasn’t love. That I was hurting. I heard myself screaming, as if all of my weird pieces that I’d locked away broke through their chains. And there was Bowie, wailing through my crappy speakers: ‘‘Watch that man! Oh honey, watch that man, he talks like a jerk but he could eat you with a fork and a spoon.’’

Looking back on it, my personal funeral for David Bowie was exactly what it should have been. There I was, covered in glitter, dressed up and in tears, crying for the person who taught me to see (and not fear) myself. After three years of muzzling her, I welcomed her back. Even in death, Bowie was saving my life. That night was the beginning of a four-month process of finally freeing myself from the Monster who swallowed me. That’s not to say that everything immediately got better – it actually got worse for a while. In ridding myself of that person, it also became apparent that my whole world was built around him, and with him went everything. But then it did start to get better (in a very nonlinear way; healing from this stuff is a process that is literally forever, and I need constant reminders to be patient with myself). June of that year was the last time I spoke to him. I’m dressing up in glitter again, I’m working my ass off for all of the things the Monster told me I’d never be able to do, I’m singing from the rooftops when I need to and letting love in again. I’m hanging onto myself – for dear life this time.

Bowie’s been gone for three years now, and I still miss him constantly. The day he died, he revived a part of me that I thought was gone forever – and, in that way, he’ll never really be gone. Your idols will teach you just as they’ll hurt you when they leave. They’ll open doors and point mirrors in your face as if to scream remember who you are whenever you choose to listen to them. You might never know them. But you always have. You know their songs, their songs will tie everything together in ways as natural as sunlight. Cry for them when they leave. Love them for helping you. Question them. Let them go.

*Name has been changed