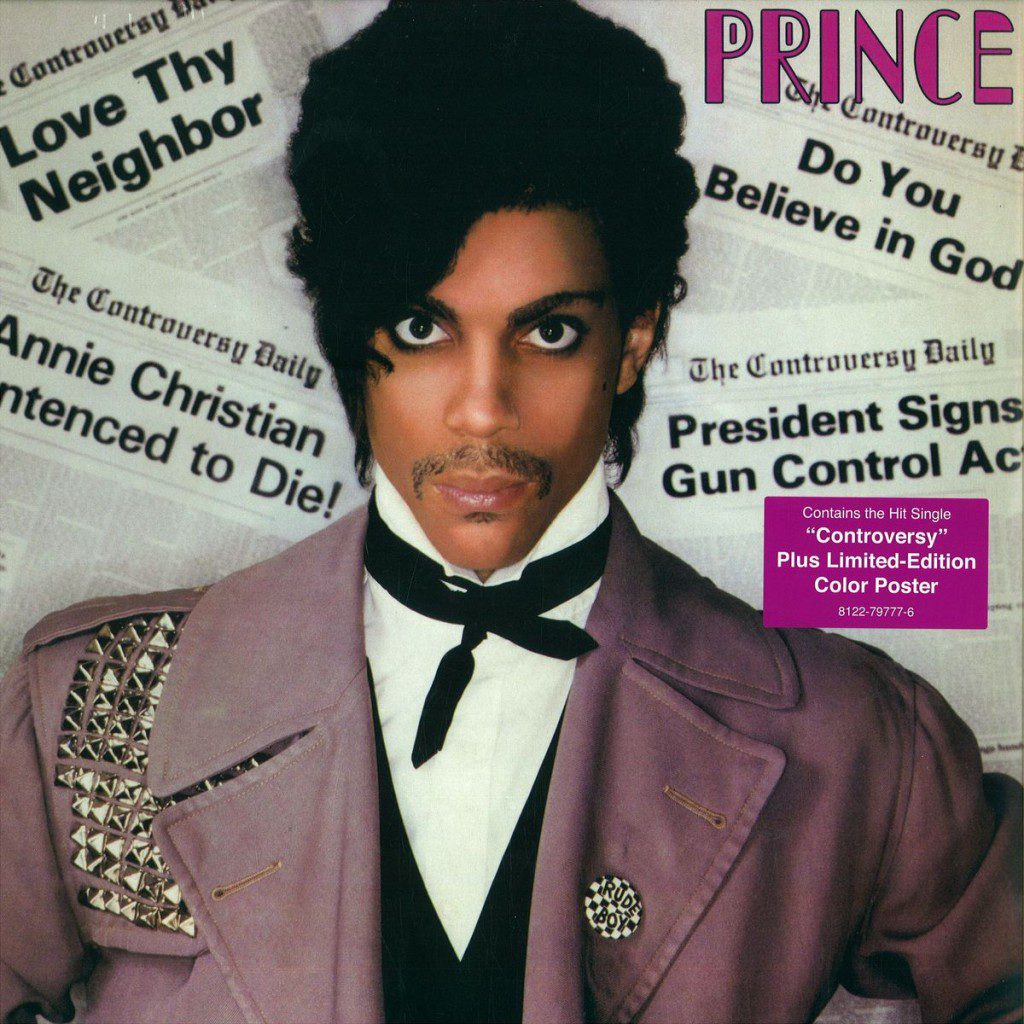

Yesterday I spent a long time thinking about Prince. Someone on Facebook declared the lyrics to “Da Bourgeoisie,” a song released in 2013, “homophobic.” And Price has, in the past, made several statements, both in person and through his music, which were anti-queer and transmisogynistic. He still blows my mind with every new piece of music he creates, but since becoming a member of Jehova’s Witnesses in 2001, Prince has not only ditched his healthy respect for sexuality, he’s lost the thing that drew me to his music in the first place—his own, unashamed sexual ambiguity. It’s difficult to separate the person and the persona when opinions make their way into music. With that in mind, I’d like to take us back to the Prince of old, to my favorite Prince album, and some of the most brilliantly crafted, critical, rebellious, and inspiring work of the ’80s: Controversy.

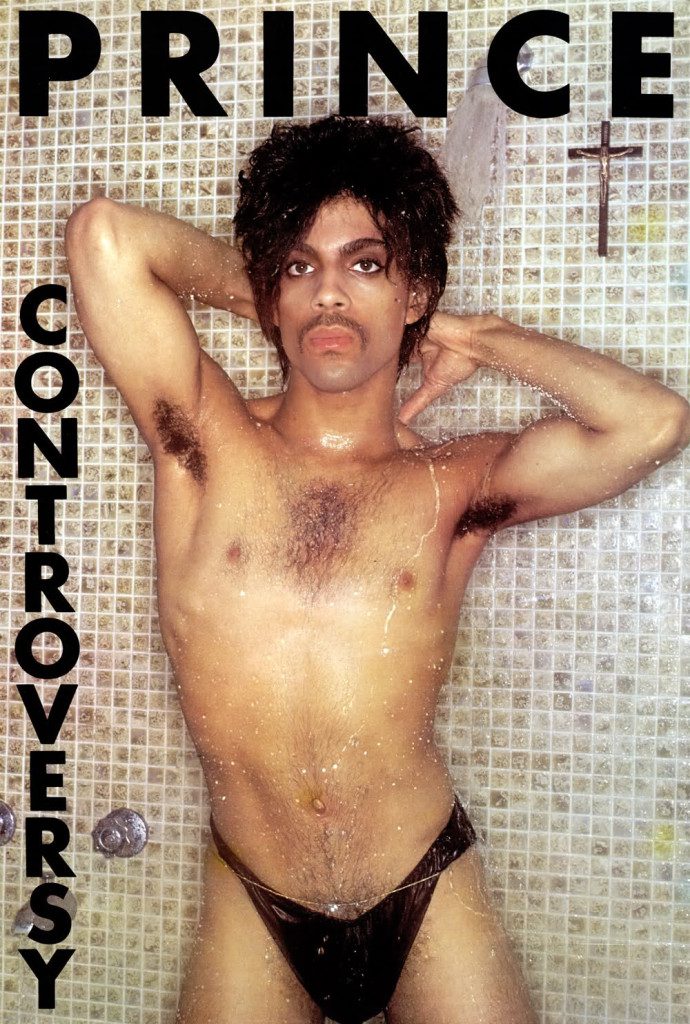

The opening track is “Controversy,” arguably the most popular from the album, and perhaps deservedly. It’s a funky, thumping, personal anthem that questions everything about society and self. He directly brings up his ambiguous identity: “Am I black or white? Am I straight or gay?” But he never actually tries to answer those questions. This seven minute-long song moves between catchy, rolling verses and textured sections meant to provoke “controversy.” Midway through the song, Prince, joined by other voices, recites the “Our Father” over the funky bass line. Then, a final section with some of the best lyrics of any rebel tune: “People call me rude / I wish we all were nude / I wish there was no black and white / I wish there were no rules.” This is a song about breaking the rules, not just for any cause, but for love. Prince, here, desires a world without boundaries on our physical, sexual, and social selves.

From there he moves into three of the most sensual songs he’s ever written. There’s the obvious, “Sexuality,” the fun and vulgar, “Jack U Off,” and the downright erotic, “Do Me, Baby.” “Sexuality” has a similar sound to “Controversy,” pounding and upbeat, and it also has a fairly direct message: “Sexuality is all you’ll ever need / Sexuality, let your body be free!” All the while he’s screeching, yelping, and beckoning the listener to him. Three quarters of the way through there’s the hypnotic mantra: “Reproduction of a new breed / leaders, stand up, organize!” It’s an electrical, in-your-skin kind of song. “Jack U Off” is the final song on the album and it has a crazy synth melody that paints visuals of a disco-lit ’80s-themed circus dance. This is a song about pleasing others. Where will Prince help you get off? In the back of a movie theater, in a restaurant, in a Cadillac. When will Prince help you get off? When you’re tired of masturbating, when you want to lose your virginity, when you’re menopausal.

And of course, there’s “Do Me, Baby,” the longest song on the album. It’s a slow, hypnotic melody in which Prince casts himself in the typically “feminine” role in a sex scene. He croons in a glazed, fragile falsetto, “Take me baby! / Kiss me all over / Play with my love” and his voice is beyond seduction. There’s no suggestion here: Prince doesn’t want to be teased, he demands to be “had.” But the actual erotica comes in at five minutes. A few funky notes pave the way for Prince to talk to his imagined lover. He sucks air in through his teeth and moans and groans, encouraging and guiding his partner. It’s dirty. It might be a little awkward if you play it in the car with your mom. But mostly it’s just entrancing.

Two tracks on “Controversy” are distinctly political or, at least, critical of the American government. “Ronnie Talk to Russia” is an overwhelming force of choral and synth melody and powerful guitar solo. It almost feels harsh, musically and lyrically. The electric guitar vibrates underneath all of the choral pomp. All the while, Prince implores Ronald Reagan to “talk to Russia before it’s too late / before they blow up the world.” At the end of the song, a jarring explosion is heard. Though this has a satirical tone, it’s cutting enough to hurt, rather than make you laugh. “Annie Christian,” though, is the song with the greatest connection to Prince’s new philosophies. It chronicles the actions of “Annie Christian,” a greedy, power-hungry, religious figure against the backdrop of a more minimalistic, experimental rhythm and tone. Prince’s voice, in particular, has an almost mechanical echo on this track. In the first verse, a glory-hound, Annie “bought a blue car” and “killed black children.” He tells her in the chorus that until she’s “crucified” for what she’s done, he’ll live his life in “taxi cabs.” The second verse focuses on the “bad girl” Annie who buys a gun and uses it to kill John Lennon. But it’s only when she tries to kill Ronald Reagan that everyone cries “gun control!” Prince highlights the actions of extremists—Christian, criminal, conservative—with Annie, the anti-Christ, standing in for the many crimes which have slipped under the radar. It was a great time when Prince was pointing out the misgivings and contradictions of American society and what they force people into.

This album, though only 8 songs long, exemplifies the kind of brilliance that can come out of a combination of risk-taking and strong ambition. These are incredibly dynamic, masterfully produced hits that curve around and between genre and theme. Personal ambiguity drips over every word. It’s fascinating. It belongs to a certain point in time, but it’s still very relevant, as a response to what is socially acceptable and as a look into the complexity of political and, particularly, sexual identity.