Gyda Valtysdottir Taps Impressive Array of Experimental Icelandic Composers For ‘Epicycle II’

A dichotomy is often drawn between classical music that one might learn in school and popular music people listen to today for their enjoyment and entertainment. But Icelandic composer and multi-instrumentalist Gyda Valtysdottir seamlessly bridges the two, with compositions that surprise the listener by drawing from classical conventions while also experimenting with fresh new sounds.

Her latest album, Epicycle II, is no exception. The collection of eight songs, recorded in collaboration with eight composers — Ólöf Arnalds, Daníel Bjarnason, Úlfur Hansson, Jónsi, María Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir, Kjartan Sveinsson, Skúli Sverrisson, and Anna Thorvaldsdóttir — creates an atmosphere that is at once ancient and modern, familiar and novel, comforting and unnerving.

The album is a sequel to her first solo album, 2016’s Epicycle, which featured works from composers like Schubert, Schumann, and Messiaen as well as contemporary ones she admired; she selected Harry Partch for his “absolute unique musical world which you cannot categorize,” George Crumb for his “sensitive and highly organic soundscapes,” and “Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus” by Oliver Messiaen, because it provided her with profound musical experiences while she was in school.

But the second Epicycle album focuses solely on contemporary composers, many of whom were favorites of Valtysdottir’s and all of whom she worked with directly. “I wanted it to be more collaborative, hence the aliveness of the composers,” she says. “Also, although I do not look at the previous record as a classical one, it has its feet in that realm. I wanted this one to be even more undefined. I also wanted to let go of control; each musician had full freedom of what they wanted to create and how much of a collaboration it would be.”

Though Valtysdottir was open to working with composers from all over the world, she ended up finding many in Iceland she wanting to work with, and so the album’s composers are exclusively from Iceland, making it “a map of the world that influenced and shaped me,” she says.

Perhaps Iceland’s mystical terrain lends itself to otherworldly-sounding music; from Bjork to Sigur Ros, the country’s most well-known artists all seem to have an ethereal, magical quality to them, and Valtysdottir also belongs on this list. Many of her songs sound almost like they were recorded in nature, but on another planet. In “Morphogenesis” (Hansson), string instruments call and answer to each other like birds. “Unfold” (Sverrisson) sounds like it belongs in a film soundtrack, accompanying a scene of majestic mountains. “Mikros” (Thorvaldsdóttir) has a suspenseful quality to it, better suited to a chase scene.

But the highlights are the tracks where she sings; the verses of “Evol Lamina” (Jónsi), “Safe to Love” (Arnalds), and “Liquidity” (Sveinsson) sound more like incantations, with her hauntingly echoey, operatic voice delivering powerful lines like “I feel the force in you of nature” and “until you feel that liquidity there is infinite space to be found.”

This theme of exploring the ways our lives revolve around one another fits with the album title. “Epicycle,” a term used to describe the planetary orbits by ancient Greek astronomer Ptolemy, refers to a specific shape: a circle moving around the circumference of a larger one. When Valtysdottir learned the word, she’d already drawn the first album’s cover artwork using a kid’s toy she got on the streets of Istanbul, and she realized what the toy had produced was epicycles.

While much of the album is abstract, it cumulatively tells a story about “the interconnection between us all, how we are shaped from our connection to others, and how we find our own authenticity by embracing others,” Valtysdottir explains. “Also, [it’s about] the unique space between each one of us. I become someone slightly different with each [collaborator]; they pull different aspects out of me. I love that — it makes me feel more free and universal.”

Each composer underwent a slightly different process with Valtysdottir: Thorvaldsdóttir wrote the piece herself, Sveinsson sat down with Valtysdottir to compose, Jónsi began by recording cello and vocal improvisations, and Hansson wrote the beginning of the piece, then they improvised the rest. She and Kjartan had a band recording with them in the studio, and Úlfur played analog synthesizers. Bjarnason’s piece was already released, and Valtysdottir fell in love with it when she heard it.

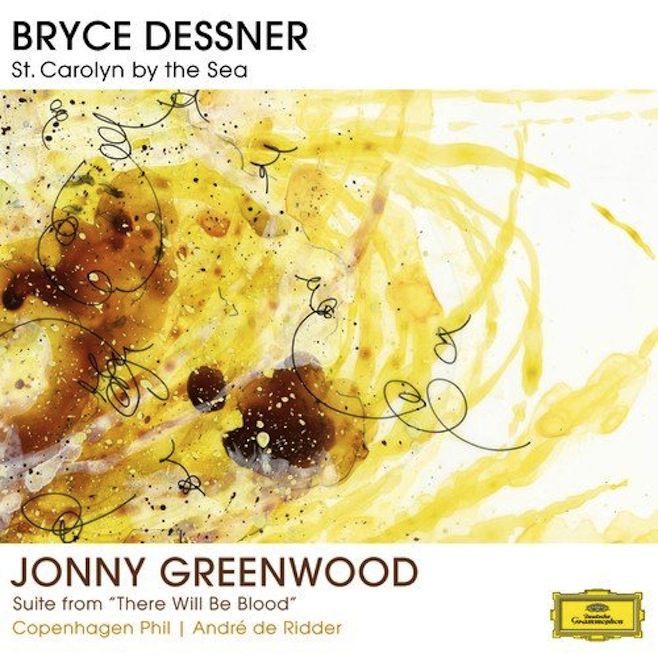

Valtysdottir has also been on the other end of this type of collaboration and appeared on many other artists’ albums. Visual artist Ragnar Kjartansson even formed a “twin project” band consisting of Valtysdottir, her twin sister Kristín Anna and Aaron and Bryce Dessner, the twin brothers in The National. They’ve created a video installation featured in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, and they also have an album on the way.

Other projects Valtysdottir’s fans can look forward to are a duo with American folk singer-songwriter Josephine Foster, several old and new songs of hers recorded with Lithuanian band Merope, and ambient pieces she composed during lockdown.

“I’d like to bundle [them] up into an album, but it’s more challenging in the bright summer nights here in Iceland,” she says. “I’ll wait for the dark days to finish it.”

Follow Gyda Valtysdottir on Facebook for ongoing updates.