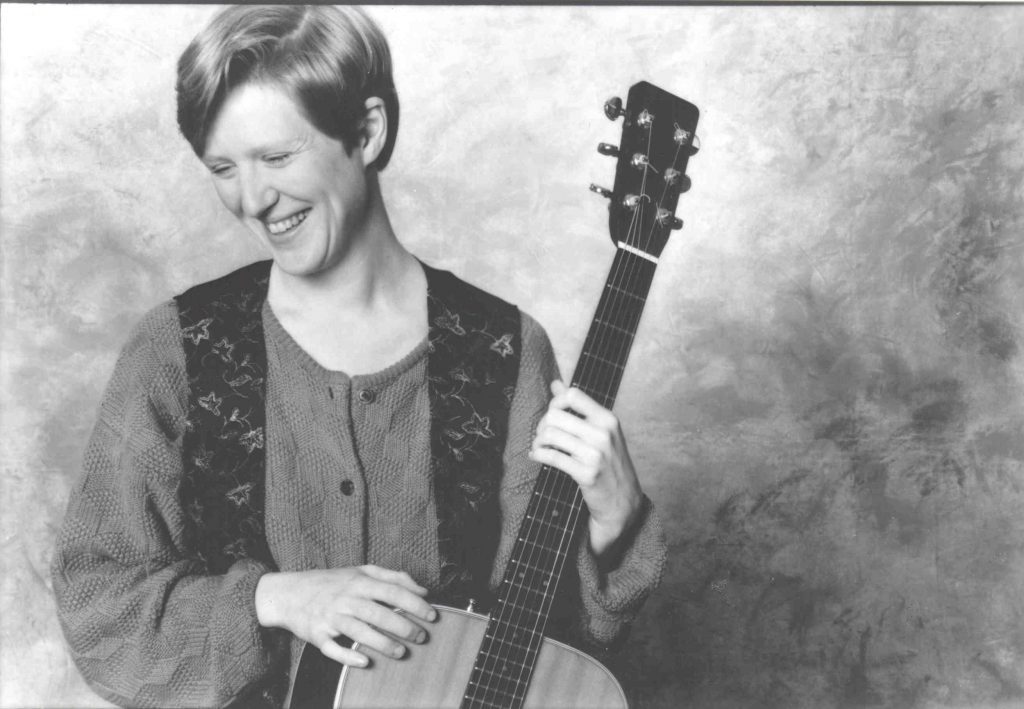

PREMIERE: Karolina Rose Supports Sexual Assault Survivors with “Runaway Angels”

Shortly after the #MeToo movement began, Polish-American indie pop artist Karolina Rose knew she wanted to write a song supporting sexual assault survivors. However, it took several years for her to feel prepared to release the end product — her latest single, “Runaway Angels.” After a lot of hard work and emotional healing, she’s sharing it today.

Working with producer Elliot Jacobson, Rose created a balance between live guitar sounds and programmed synths and drum machines for the song, which embodies the dark power-pop aesthetic she’s known for. The lyrics describe the inner turmoil involved in processing sexual trauma: “You’re something in my eye/I make tears and wash it all away/All those times I tried so hard/Fantasize just to make it through the day.” In the chorus, she sings about “a place to hold these hollow hearts,” which to her means that it’s okay to “feel really empty for a while, and we’ll hold onto you while you feel that way,” she explains.

Since the topic of the song hit close to home, she sat on it for a while after writing it. “I wasn’t able to listen to the song for a long time because it would make me cry — I’d get really triggered by my own song,” she says. It ultimately took an ayahuasca ceremony for her to feel emotionally prepared to put it out into the world.

When the shaman who conducted Rose’s ceremony listened to “Runaway Angels,” he told her, “I hear pain in this song… this song has a dark energy.” She doesn’t disagree with his assessment, but she views the music as cathartic rather than polluting. “I think overall, it can be a healing tool, because I don’t think there’s anything wrong with bringing to light those shadow parts of yourself and feeling that in music,” she says.

In fact, she hopes those who listen to it can relate to her pain and understand they’re not alone. “It was just this collective support that I wanted to transmit in the song — this collective pain but equally collective support,” she says. “I feel like all of these primarily female victims — the angels — need the world’s support.”

Since the world is undergoing another reckoning of sorts today, she’s glad to put out the message in the song right now, as its messages feel equally suited to the fight for racial justice. “For so many of us that are not racist, it’s so obvious — like, of course we love everyone — but you have to step forward and actually show your support,” she says. “Otherwise, if you don’t say it, you’re remaining silent. And that’s how I felt when I was writing this song about the fact that it’s so hard for sexually abused victims to come forward when they aren’t guaranteed support.”

The track is off her upcoming EP, Rosemary, which comes out August 21 and explores the process of healing and finding love through four songs. It also includes “Greytopia,” a more upbeat, Lady Gaga-esque single about transcending difficulties; a dark, electronic cover of Shakira’s “Objection“; and “White Lies,” a dynamic, danceable track that’s currently unreleased.

Rose was working in investment banking in New York City when she decided to take a leap of faith and follow her passion of making music. “I felt like I wanted to have more out of life, that I wasn’t going to be okay with a stable, secure job and that’s it,” she says. “I thought I had more to say about my story.” Outside her day job, she practiced guitar and wrote songs, then started doing acoustic shows. She wrote and recorded her first music in New York, with her 2019 debut EP Invicta carrying a similar theme of strength, then spent three months traveling Europe as she worked on Rosemary before settling in LA.

The videos for the EP were filmed in a Croatia villa that Rose swears was haunted, which inspired a scene with an apparition in the not-yet-released “Runaway Angels” video. After a filming marathon, Rose fell asleep at the wheel of her car and almost swerved off the road. She remembers the friends she was filming with telling her, “‘This could happen to anybody. Don’t feel that way.’ They were helping me, so it was just like a family. … I think this just adds to how much this means to us.”

Because she was able to release so many negative emotions in “Runaway Angels” and the rest of Rosemary, she predicts that her future music will have a whole new sound. “I feel like my pain is trapped in those songs,” she says. “Anything recorded going forward from the new me, I’m pretty sure, is going to be really different.”

Follow Karolina Rose on Facebook for ongoing updates.