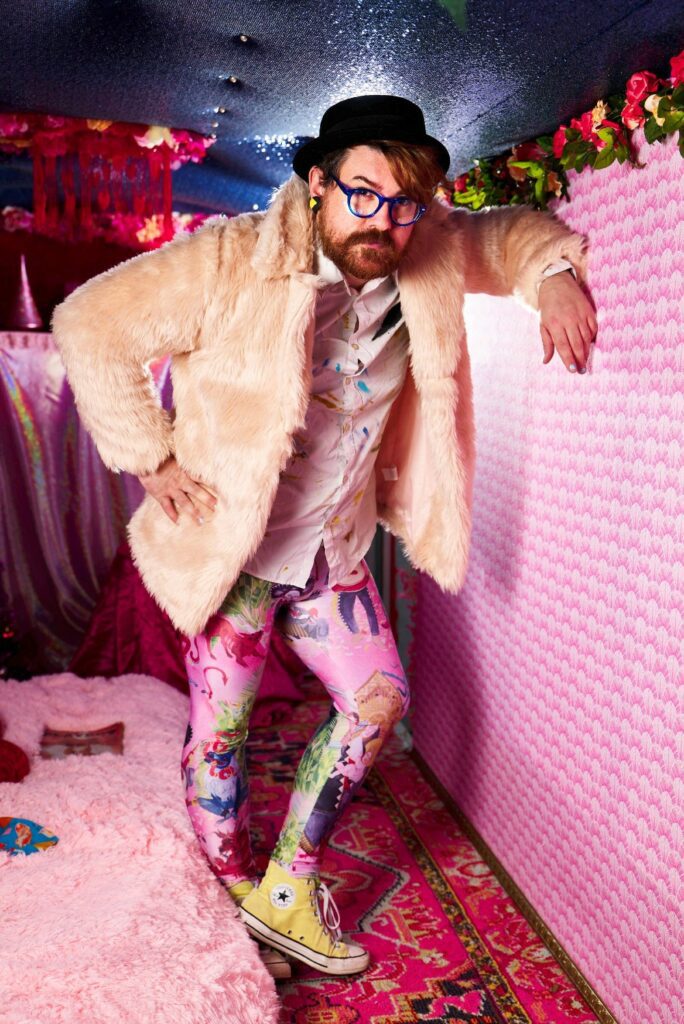

PREMIERE: Adeem the Artist Reclaims Identity With Cast Iron Pansexual LP

There are few albums that capture such an array of the queer experience quite like Cast Iron Pansexual, the new LP from Adeem the Artist. Officially out Friday but premiering via Audiofemme today, the record bursts with personality, marked with deep moments of personal retrieval and reflection on queer identity and rural heritage, encompassing some trauma but also recovery from it. “I have found sexuality isn’t just who you kiss/It’s part of your unique identity,” they sing over plucky guitar strings.

“I Never Came Out” cracks open the conversation with plain-spoken honesty and a pinch of cheekiness. “Oh boys in tight blue jeans are driving me crazy/Boys in tight blue jeans with legs that go for days,” they howl with a bluesy growl. “Boys in tight blue jeans are driving me wild/With their poise and impeccable style.”

Unlike most LGBTQ+ people, Adeem, who now identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns, really did not have that pivotal coming out moment ─ although the release of the record “feels like a definitive coming out moment,” they tell Audiofemme with a laugh. “At this point, it doesn’t feel like it’s something I’ve missed out on.”

Partly because of this, Adeem says they harbored reservations that they “could be centering myself in something that wasn’t mine” with the record. “Last year, I was thinking about identity and who I was when I didn’t see the same friend groups, [asking myself] who am I when I’m not experienced by other people?” In their story, a certain anxiety descended around them when “my friends started treating me differently and interpreted my jokes differently,” they say, noting a song called “Apartment” confronts this, head-on. “That was really scary ground to step into.”

Cast Iron Pansexual began as an entity unto itself toward the end of 2020, initially prompted by Adeem’s Patreon supporters, who desperately wanted a new batch of music. Writing a song a week, Adeem had “urgency to write” through such accountability. “I need deadlines,” they remark.

Some songs are much older, but a bulk of the record was written in the early months of the pandemic when they felt increasingly “isolated” from the world they once knew. “So much of my community is walking around in market square downtown and bumping into people I know or going to the grocery store and chatting with people from the show I saw,” they offer. Normalcy was completely ripped away, of course; Adeem says they “didn’t even make eye contact so I didn’t have to figure out how to communicate” with the implications of the pandemic looming so large over casual run-ins.

Adeem hadn’t really done much writing about their sexuality. While their world was opening up through extensive self-exploration, they were greatly influenced by nonbinary model and gender activist ALOK and their book Beyond the Gender Binary, released in 2020. Adeem also dove into “internet exploration of gender and gender expression,” they say. “All of that was happening while I was examining these early feelings of queerness and trying to pin it down.”

“I’m not trying to represent all queer people by saying I’m queer. I’m just accepting myself for who I am. I allowed myself to step into it,” they add. “I’m nonbinary, but that doesn’t mean I understand everyone who is nonbinary and can speak for them.”

A vital part of Adeem’s journey was growing up in a Christian household. Originally from Locust, North Carolina, they were baptized when they were just a kid, around five or six. Even then, they “had a pretty good understanding of the metaphysical and existential repercussions of making a decision like that.” Adeem’s church was comprised of devout believers ─ so much so, they were “waiting for Jesus to show up on cloud to take us to the new earth” ─ but Adeem firmly left the church when they were 23 years old, in 2011.

Over the next decade, they “came back a couple times,” including in 2014 when they entered the Episcopal Service Corp. During that time, Adeem discovered the teachings of two theologians named John Shelby Spong and Matthew Fox, both of whom “didn’t believe Jesus ever rose from the dead.” That was a light bulb moment. “When Spong entertains the idea that maybe Jesus is a composite of different characters, and all this could be a metaphor, that was cool to me. There’s still things in there I could be interested in if it’s just a mythology,” they say.

“Going to Heaven,” clocking it at under a minute, is the most forthright in reconciling what they were taught, coming to terms with the truth, and what faith means today, if anything. “On the back roads of my hometown/I was baptized once or twice,” they sing, as their story unfurls. “By some grifters in a storefront church/In exchange for eternal life.” In true Adeem fashion, such heaviness is sliced with refreshing humor. Later, they sing, “I can’t wait to go to heaven/Gonna have a gay old time in heaven/Fuck me, I’m going to heaven/I made a steal of a deal that day.”

Adeem wrote the song amidst a major professional change. They’d had a corporate job for a few years but began to feel the mental/emotional pressure — so they quit. “I’m just not good at having jobs. I’m definitely an artistically-minded person,” they say. Adeem then began doing various odd jobs for some friends to make ends meet, and one of those was driving up to Spencer Mountain to retrieve produce from The Mennonites who lived there. “I was driving through the forgotten towns of Tennessee and thinking, I can’t imagine being 13 and living in a town like this, where the Food City parking lot is lit up on a Friday night because there’s nowhere else to go.”

“I was really ruminating on heaven and hell,” they continue. “It’s important to some people. I would say now I could not careless, but when I was younger, especially in the years after leaving the church, it was heavy for me. I was thinking about how there are people who actively think I’m going to hell. I had this idea of writing a modern hymn and shoehorning in ‘Fuck me, I’m going to heaven!’”

Perhaps Adeem’s boldest entry is “I Wish You Would’ve Been a Cowboy,” a dismantling of country staple Toby Keith’s 1993 hit “Should’ve Been a Cowboy” into an ode of accountability. Adeem examines Keith’s role in perpetuating the extreme patriotism which sprouted up in the aftermath of 9/11 and the deeply troubling exploitation of the working class.

“Your twenty minute song props up Fascists/While you brag about kicking asses/With a boot in your mouth, exploiting the American South,” Adeem sings. There’s both a melancholic weight and an icy rage to their performance, specifically addressing Keith’s 2002 song, “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American),” which Keith alleges he wrote in just 20 minutes.

Looking back, Adeem says they were not anti-Toby Keith in the early aughts (that would come later). “I was probably pretty ambivalent toward it. I’d discovered Nirvana, and I was in a different space,” they recall. Their family moved to upstate New York that year, and much to Adeem’s shock, the area “maybe had always been kind of racist. It felt like there was renewed strength behind it.”

“There’s a theory country music was killed by 9/11. I’d been ruminating a lot on Toby. I like his music. He’s a great songwriter. I don’t think anybody would contest that he knows how to write a song,” Adeem adds. “He also wrote the shittiest songs in the aftermath of 9/11. They’re so violent and gross. I did so much googling to see if he ever apologized or ever reckoned with this. And he hasn’t once. The only thing I could find was him saying, ‘I wrote this song in 20 minutes.’ And I toiled for a year on this song, at least, trying to get the phrasing right and make sure I said what I wanted to say.”

They also reached out to Palestinian-American poet named Summer Awad to ask if she would take a pass on the song. “I wanted to talk about it, but I didn’t feel I should. My perspective is so much of a white redneck in America. So, I sent the idea to her, and she sent me back a bunch of the same ideas that were written from that perspective. I didn’t experience any Islamophobia or see much in my circle because… everybody was white,” Adeem remembers. “I wasn’t going to put it on a digital release or anything. I didn’t want to be unfair. I lob some accusations at him, that he is exploiting the working class. And I actually don’t think it is unfair. Who can say? Maybe Toby is picking the themes for the same reason I pick the themes I want to. Someone could say I’m exploiting the queer community for releasing this album, which is obviously not true. But I was worried about the nuance of it.”

Adeem was struck by a few other things. Around five years ago, they discovered the work of Roger Alan Wade and his 2010 album, Deguello Motel, which was “full of really brash poetry,” including the song “Rock, Powder, Pills.” “It was the first time I think I related really strongly with country music since I was a kid,” says Adeem, who largely grew up listening to pop-country on the radio. Wade was a gateway into much richer country music, like Guy Clark and John Prine, and this revelation “made me feel connected to being from the South. [It] was really healing for me.”

Adeem’s “origin story” is as country as they come. Their mother worked overnights at Texaco when their father “popped in to get some road beers, had a one night stand, did the Presbyterian thing and got married.” Through both their musical and personal journeys, Adeem has come “to listen to country music and view that as poetry instead of a reason to be embarrassed. It was like finding a gem in the backyard,” they say. “The more I grew into that, I got to thinking about my twang and how I spent so many years trying to cover it up. I didn’t want to be the redneck in a school in New York.”

Much of Cast Iron Pansexual is a love letter written to “the barefoot hick that I was as a child,” Adeem says. “I think it started to give me a lot of bitterness to those artists and that culture that made me feel so estranged in the early aughts. It got to the point where it was like ‘I don’t fit in here. There’s no place for me.’ And there really wasn’t. It wasn’t a scene that was welcoming to people who looked and thought like I did.”

The album arrives five years after 2016’s Kyle Adem is Dead, another watershed moment in their ongoing life story. In a blog post, written around the same time, Adeem wrote openly about “the religious questions that had chased me for years, the troubled relationships I was clinging desperately to, and the difficult work of sorting reality from fiction in a household where mental illness was often a guiding hand.”

Adeem’s growth and strength is palpable these days. Five years is an eternity, not only in the world at large, but on a micro level. “That was a big moment for me. I’d been going by Adeem with my friends for a long time, but ‘Kyle Adem’ was a moniker I was using to blend ‘this is who I was born’ and ‘this is who I want to be.’ I reached a point where people were calling me Kyle a lot, and it was triggering shitty memories of growing up in the South and the way people said my name and the way the world interacted with me then.”

Adeem dropped the name as a way to reclaim their worth and take up some space. Now, going by Adeem the Artist, they remind themselves “why I want to make albums and write songs.”

Adeem the Artist’s Cast Iron Pansexual is a mighty declaration of self, identity, and resilience that comes with living comfortably in one’s own skin. Even if they wouldn’t call themself a trailblazer, they’re certainly living proof that who you are is perfectly okay.

Follow Adeem the Artist on Twitter and Instagram for ongoing updates.