Five Can’t-Miss 2021 Albums from the Eclectic New Zealand Music Scene

Australian music press and fans often look to the US and UK when seeking new sounds. It is to our detriment though, when so many diverse and divinely talented musicians and producers are emerging from the North and South Islands of New Zealand (Aotearoa in Maori).

From the nufolk, gothic, country-tinged ballads of Kendall Elise to the fresh, ambient pop of French For Rabbits, the heartbreakingly soulful Hollie Smith or the dark, strange and compelling Proteins of Magic and OV PAIN, there’s every reason to indulge in a deep dive into New Zealand’s 2021 album releases. Do yourself a favour, even, and book a trip. The epic, abundant natural beauty of the landscape and its diversity might make sense of the enormous variation in art and artists from this Pacific destination.

The following list is but a drop in the ocean of New Zealand’s music scene; in the coming year, readers can look forward to many more features on New Zealand artists in Audiofemme’s Playing Melbourne column. Stay tuned!

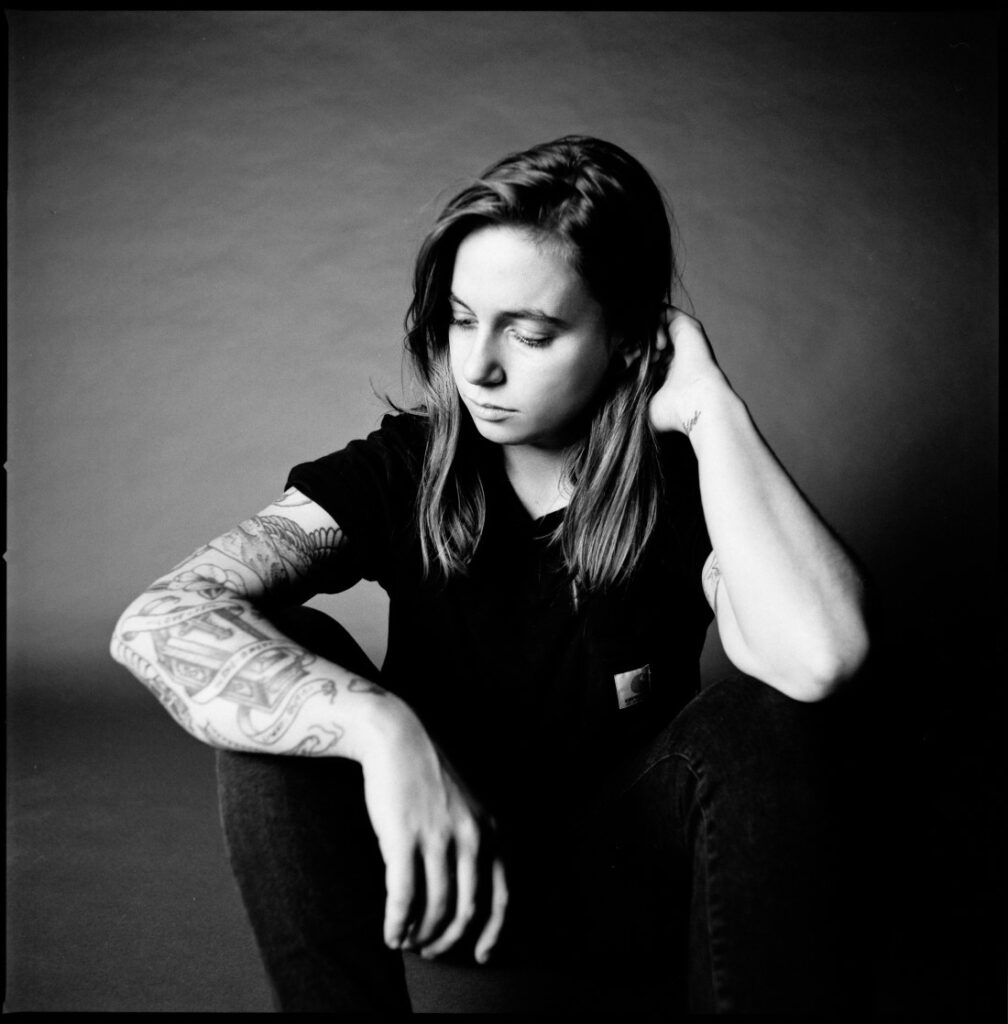

Kendall Elise – Let The Night In

Kendall Elise, from Papakura in Auckland, released the darkly soulful country album Let The Night In in August. Her sophomore effort is rich with hauntingly romantic, gorgeously spare ballads. “I Want” is proof Elise can’t neatly be classified as pure country. It’s a crooner, wrapped up in a plaintive, weeping guitar embrace that speaks of open windows and a thundering storm approaching.

She admits she wears her jeans too tight and likes her music too loud on a rip-roaring cover of Suzie Quatro’s “Your Mamma Won’t Like Me;” furious, barnstorming guitar drives the message home with grit. There’s a whisper of traditional English folk ballad “Greensleeves” in the guitar-based melody and melancholy harmonies on “A Kingdom.”

After gaining attention with her self-produced EP I Didn’t Stand A Chance in 2017, she drew enough crowdfunded support to release her debut album Red Earth in 2019. Let The Night In was recorded in lieu of her COVID-cancelled 2020 Europe tour – it’s sparing, stormy, sultry and stunning across all 10 tracks.

French For Rabbits – The Overflow

Salty air, sparkling ocean waves, the brightness of sun glinting off mossy rocks – these refreshing sensations are easily evoked by Poneke, Wellington band French For Rabbits on their track “The Overflow.” It can be found on their third album of the same name, released in November.

Brooke Singer adds vocal gilt to the delicate instrumentals and dreamy electropop of guitarist John Fitzgerald, drummer Hikurangi Schaverien-Kaa, and multi-instrumentalists Ben Lemi and Penelope Esplin. While their past albums – 2017’s The Weight of Melted Snow and 2014’s Spirits – have rooted the mood in more solemn, sad territory, there’s a languid sweetness, a freshness, to the ten tracks showcased here.

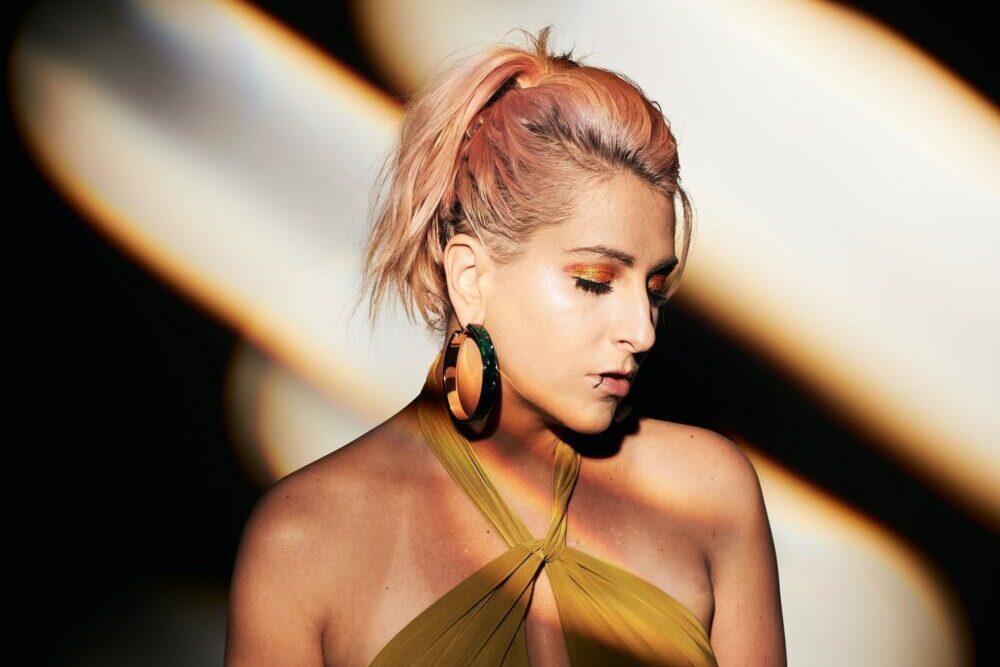

Hollie Smith – Coming In From The Dark

Hollie Smith released her fourth solo album in October, and Coming In From The Dark more than justifies her four-decade strong career. The album showcases high-caliber collaborations, including the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (which features on the dramatic, full-throated title track), Sol3 Mio (on theatrical pop-operetta “You”) and Raiza Biza (on the slow burn of trippin’ R&B slow-trap “What About”).

Ultimately, the full-body feels are delivered simply by Smith’s sensational vocals. She’s an established artist in New Zealand who began singing in earnest as a teenager in local jazz outfits in Auckland. She went on to record and tour internationally with her father, an expert in Celtic music, before taking the solo path from her Wellington base in the 2000s. Her 2007 debut album Long Player sold double-platinum and scooped a bunch of New Zealand Music Awards. She followed it up with Humour and the Misfortune of Others in 2010 and her third album Water or Gold in 2016, as well as two collaborative albums: Band of Brothers Vol. 1 with Mara TK and Peace of Mind with Anika Moa and Boh Runga. Why hasn’t Australia tried to claim her yet? Maybe we tried and failed. Our loss; Smith is never forgotten once you’ve heard her sing.

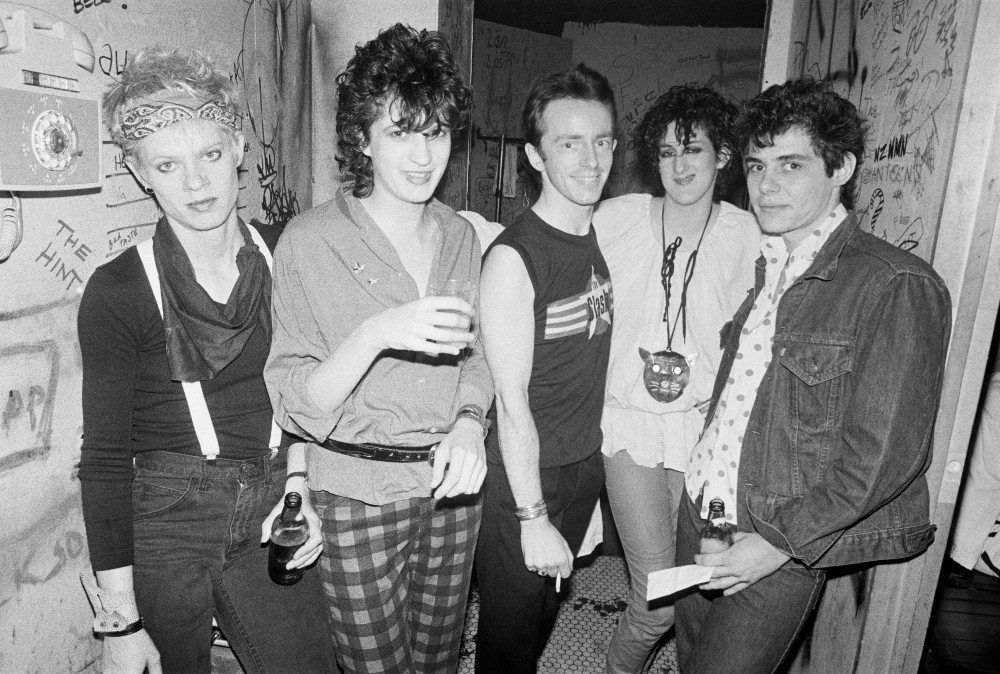

Proteins of Magic – Proteins of Magic

How do you describe the unusual, totally captivating strangeness of Kelly Sherrod and Proteins of Magic? Just like that, I suppose. It’s a bizarre, wonderful pagan spell that’s conjured in her cross-border project that sees her living and working between her homes in Auckland and Nashville.

There’s a Laurie Anderson vibe to Sherrod’s operatic, gothic delivery over esoteric electronica on her debut self-titled album, released in August. If you can imagine, it capably combines elements of Enya’s dramatic, atmospheric “Orinoco Flow” and the odd sound-and-voice nightmare vision of Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman” with the hyperreal, disjointed techno-cool of Miss Kittin & The Hacker’s “Frank Sinatra.” But then, “The Book” is a piano-led, ghostly lament that is absolutely, heart-rendingly beautiful, defying comparisons. In November, Proteins of Magic released stand-alone single “Willow,” a multi-layered, witchy brew of synths, bouncy basslines and punchy digital drums.

Sherrod’s musical debut was as frontwoman for Punches in 2003, followed by playing bass for Dimmer before she moved to Nashville in 2009, painting and recording in her home studio when she wasn’t touring with the likes of The Brian Jonestown Massacre. Her schedule is busy with festivals in New Zealand in early 2022, and seems ample reason for organising a January roadtrip via Auckland.

OV PAIN – The Churning Blue of Noon

Renee Barrance and Tim Player are Dunedin-originated, Melbourne-based OV PAIN. Their second album The Churning Blue of Noon is a more eclectic, experimental beast than their debut self-titled album of 2017. The duo had been nourished by a diet of drone, free jazz and instrumental work, and combined with the apocalyptic global pandemic scenario, their creative vision became murky with gothic, end-of-times moodiness. The August release was admittedly recorded in Melbourne, the duo’s second home.

Player is the Bela Lugosi-esque narrator on “Ritual In The Dark Part 1,” over a hollow-hearted digital organ. Warped, distorted synth fills the atmosphere, and from a ghostly parallel universe, Barrance’s dystopic vocals croon and hum on “Excess and Expenditure.” The track epitomises the feel of the whole album, a dark masterpiece.