ONLY NOISE: On Loving the Beatles As a Black Woman

ONLY NOISE explores music fandom with poignant personal essays that examine the ways we’re shaped by our chosen soundtrack. This week, Stephanie Phillips finds a way to relate to the Beatles – even though, as a black woman, their version of Britishness didn’t reflect her own experience.

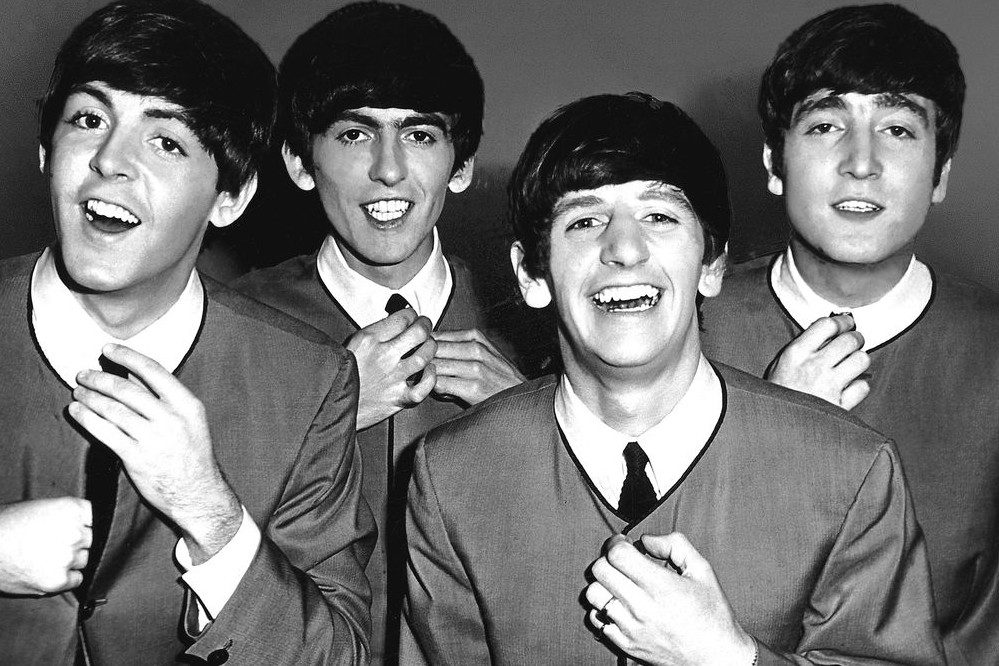

Whether it was the power chord-driven emotional roar of Olympia’s Sleater-Kinney or the proto-riot grrrl wail of X-Ray Spex, as a young black girl who who spent all of her free time devouring new music, these musicians made my little teen self and all of my complex emotions feel seen. Yet, growing up in England in the ‘90s, there was one inescapable group that epitomized the way the country liked to see itself: The Beatles. As four white men who first made their name first reinterpreting the work of black artists, The Beatles were as British as the Empire itself – a glorious example of the British bulldog spirit and post-war triumph. In a country that, at the best of times, treats people like me with complete disregard (and at the worst has seen grown men making monkey noises at my ten-year-old self), how could I possibly feel connected to the four men they’d chosen as their ambassadors of Britishness? I wrote them off for as long as I could, deeming their work too misogynist, too irrelevant, or too old. So I was as stunned as anyone when The Beatles became one of my biggest influences as a musician and lover of music history.

The Beatles were so ubiquitous I can’t recall where I was when I first heard their music. Maybe I had to sing it as part of the alternative, contemporary songs portion of service at my church. It could have been background noise whirring from another TV special as I obliviously played with my brother as a kid. There’s always a chance the Fab Four blared out over tinny speakers at the local supermarket as I perused the perishables aisle with my mum. You were never introduced to The Beatles, they were just there, woven into the fabric of everyday life, an immovable presence in the British musical canon, one which no one would openly question.

Almost because of their popularity, they are also one of world’s most misunderstood bands. The source of the misinformation is usually middle-aged, know-it-all male fans – the kind who only drink real ale and, after a few pints, speak too loudly on the opinion that modern music is rubbish. These tiresome messengers of the drab bring the Four down to their level of mediocrity with their lacklustre covers of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and their insistence “Hey Jude” is the best Beatles song. It’s not, by a long stretch. This left me with the impression that the Beatles’ music only sounded sickly, sweet, and terribly dated.

The sad dad army wreaked havoc on the Beatles’ legacy and that’s even before you get into the steaming layers of toxic masculinity surrounding the band. Each member has had to answer to how they treated the women in their lives and we all know the stories of violence and macho aggression that are associated with John Lennon. How could I love a band who perhaps didn’t love women like me? I didn’t know how to get over these barriers. I decided I couldn’t and gave up, following my path into the exhilarating world of riot grrrl.

My early twenties were spent lying in my room listening to Giant Drag, Le Tigre and The Long Blondes, expanding my tastes by finding bands that were connected to them and repeating that same process. Looking back it was inevitable my aimless mission to devour all the music would eventually lead me to The Beatles; much like Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, it was obvious that many bands would be inspired by or connected to the Beatles’ in some way, especially with the music industry continually pushing them to the forefront. Given my disdain for the Beatles’ association with British culture, it seems apt it that American bands eventually drew me into the Beatles’ genius. The Pixies, Breeders, and Throwing Muses all covered songs from the White Album; some were b-sides lovingly recreated, others were carefully reinterpreted takes on the original.

The Pixies’ cover of “Wild Honey Pie,” for instance, took what was a short, frenzied, carnival-esque snippet of a song and transformed it into an art rock scream fest. The Pixies used the repetitive nature of the song to further amp up the passion at the beating heart of the track. It was a brilliant homage to the kooky original, which was one of a collection of songs that illustrated the Fab Four’s love of all things odd.

The Breeders recorded a slower, moodier take on “Happiness is a Warm Gun” on their debut album Pod, while Throwing Muses released on haunting version of “Cry Baby Cry” on their 1991 single “Not Too Soon.” All in all the mysterious lyrics, complex time signatures and raw attitude spoke to me. I needed to know more, so I sought out the album.

The pressure to automatically revere a band instantly sucks all of the joy out of the listening process, like force-feeding yourself chocolate cake – it’s good, but you’d prefer a smaller slice on your own time. Taking The White Album in note by note, the world of The Beatles started to reveal itself to me. Far from being the unlistenable nonsense I always associated with them, the album was challenging, deep and experimental without showing off. I finally understood the melancholy outlook of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and its untamed classic rock guitar noodling. There were manically upbeat songs like “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey,” sparse proto-goth tunes like “Dear Prudence,” and garage blues punk on “Helter Skelter.” I listened to the album over and over again, taking in the incredible number of influences and genres that made this epic project. The album wasn’t coherent – the songs rarely followed any pop structure, and had unpredictable twists and turns. I was fixated with these sounds and finding out how they came to be. With each listen I heard so many of the bands I already loved in this one album. Turns out, I had been listening to the Beatles far longer than I’d realised, and I had to admit I’d been was wrong about them. They were a missing part of my music history puzzle.

If I was wrong about this album, I had to reason I might have been wrong about the rest of their music, so I kept listening and searching. There was a lot of ground to cover – decades worth of recordings, documentaries, films, rereleases and a lifetime’s worth of coverage. I devoured it all and came out the other end a Beatles devotee.

I had to admit that their cheeky, laddish attitude was addictive to watch, and a lot of the praise they were given is arguably true. I found as much beauty in their early recordings as I did their backstory. The reason their work resonates with so many is because their songs were simple and about universal themes of love and lust. The desperate appeal to an inattentive lover on “Please, Please Me” is sadly relatable. When I heard the crack in John’s voice on middle eighth of “This Boy” it hit me as hard as as any of the most eloquent poetry on heartbreak and loss. When The Beatles got it right they managed to create a world where anyone, no matter their background, could live vicariously through them. That’s when it clicked. The real winning element of the Beatles goes beyond their songs and exists in their story as a group.

And yet, I know so many black people who struggle to connect with the band, that feel disconnected from the white culture the band represent, and are far too aware that the Beatles built their reputation by imitating African American soul and R&B. I felt the same and it is true. The Beatles connection to whiteness and England is rarely discussed. It was a huge barrier that made liking the band seem insurmountable. The gatekeepers of rock and roll had told me that this was the greatest band in modern history, erasing the contributions of the genre’s black pioneers, and that was extremely off-putting. But the more I listened, I heard the influence of black musicians, like Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Motown acts like The Marvelettes. The Beatles could interpret any music style to their own benefit, and were emotive and adaptable songwriters, but unlike Led Zeppelin or Eric Clapton, they did not try and pass off black innovation as their own. The Beatles covered their favourite songs, put their own spin on them so as not to rip them off completely, and pointed fans in the direction of artists they were inspired by. Their effort to do so still resonates today, considering many white musicians fail to meet these basic requirements.

As a black female creative who often struggles to buck up my confidence and go out into the world, listening to The Beatles gives me the strength to imagine what I could be. It reminds me what I could create if capitalism, white supremacy and misogyny weren’t rooting for me to fail. Because despite the numerous books and documentaries declaring so, John, George, Paul and Ringo were not geniuses. Their ten year soap opera of a story gave me permission to dream of what could happen if I had everything – the money to buy whatever I wanted, the time to write, the confidence provided by millions of adoring fans. Perhaps when teenage girls screamed themselves into delirious frenzy at the sight of the boys, they weren’t just caught up in teenage lust, but were hungry to be any part of something as alive and powerful as rock and roll.

In a world where black bodies are policed at every available moment and black joy is looked on with suspicion there is rarely an opportunity for black people to dream freely. It’s why I always tell my friends about the power of The Beatles, though my sales pitch often falls on deaf ears. Who would believe black people could find respite in the words of four white guys from Liverpool? Though it’s likely that was not their intention, their enduring music gives me space to fully realise myself. I can sit back and take in the best of Revolver or Rubber Soul while imagining who and what I could be as a musician, a music fan and a black woman.