Massive 50th Anniversary Reissue of Plastic Ono Band Sessions Positions Yoko Ono as Musical Maverick

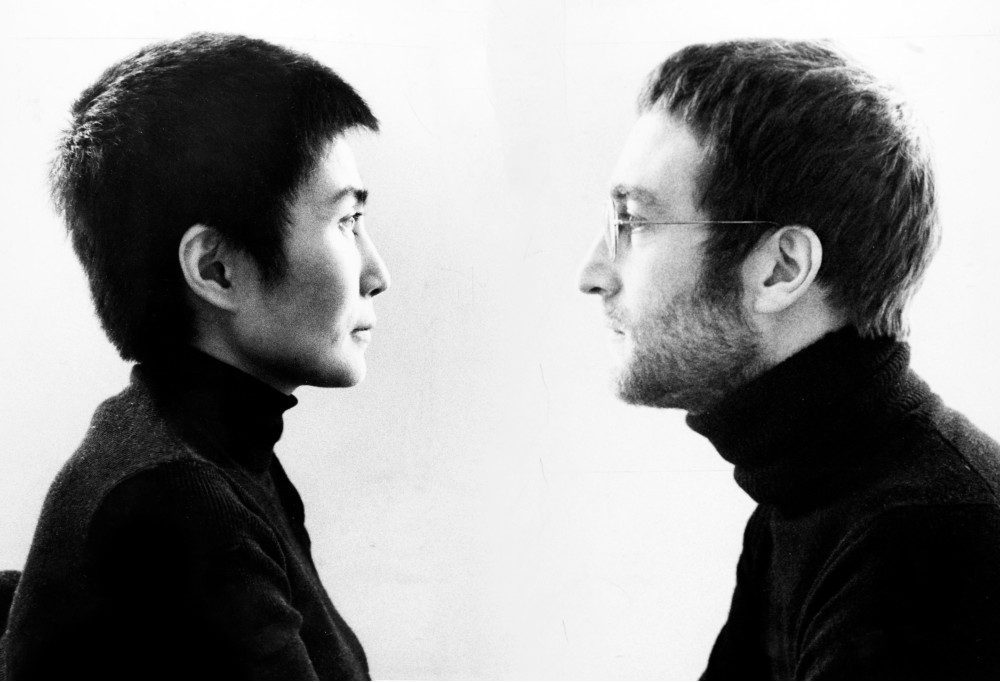

On October 10, 1970, John Lennon was busy working on his first solo album at EMI Recording Studios (not yet rechristened “Abbey Road,” after the Beatles’ album of the same name). The sessions had been going on for two weeks. But on this day, his wife, Yoko Ono, was finally going to get the opportunity to make her own kind of music.

Having just finished mixing his song “I Found Out,” Lennon, on guitar, started jamming with bassist Klaus Voorman and fellow ex-Beatle Ringo Starr on drums. After vamping through some Elvis Presley and Carl Perkins numbers, the power trio began to stretch out. And as Lennon’s playing became increasingly wild, slashing at his instrument as he spiraled down the scale, he shouted out for Ono to join him, and she did.

Ono’s vocalizations were a desperate, keening sound, matching the twisted noise from Lennon’s guitar, her persistent cry of the single word “Why?” becoming the aural equivalent of Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream. Lennon was enthralled. “She makes music like you’ve never heard on earth,” he enthused to Rolling Stone later that year. “And when the musicians play with her, they’re inspired out of their skulls.”

At the time, the general public didn’t agree. When John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band were jointly released in December 1970, Lennon’s album was heralded as a brave, uncompromising work. Ono’s was overlooked, or derided; she recalls being sent photos of her records stuffed in a garbage can. “So many people didn’t understand her,” says Simon Hilton, production manager of the new JL/POB reissue – out today, in honor of the double album’s 50th anniversary – which also includes Ono’s sessions on the “Ultimate Collection” version of the set. Hilton believes she experienced backlash not only because she was a woman, but because of her otherness: “She sounded a bit funny, and she liked screaming.” But over the years, that assessment has changed. YO/POB has come to be recognized as a pioneering album, one that laid the groundwork for independent music and alternative rock to come.

The original album is bold and bracing; there simply wasn’t another record like it. “Why” launches the album with a furious assault that grabs you from the second it erupts and doesn’t let go. In contrast, “Why Not” is a leisurely stroll, the musicians providing a steady backbeat to Ono’s ululations until the final minute, when it gradually speeds up, then burns out, drowned out by the sound of a subway rushing by. The title of “Greenfield Morning I Pushed an Empty Baby Carriage All Over the City” echoes the cryptic “instructional poems” in Ono’s book Grapefruit, and the song itself is equally ominous, opening with an industrial droning, Yoko’s vocal cutting throughout the piece like a mournful siren.

“AOS” is drawn from a 1968 rehearsal with Ornette Coleman. It is a stark, spare track (aside from a sudden torrent of sound in the middle), Ono holding her own in the company of Coleman on trumpet, Charlie Haden and David Izenzon on bass, and Ed Blackwell on drums. “Touch Me” is all sharp edges and jarring rhythms, interrupted by what sounds like a tree cracking in two, then morphing into something slower and more distorted. “Paper Shoes” has an agitated, percussive beat percolating underneath Ono’s almost breezy, wordless vocal, swooping in and out.

Ono herself had little familiarity with rock music or its culture when she began working with John Lennon. Born in Tokyo in 1933, and growing up in both Japan and the US, she was a classically-trained pianist, who dreamed of becoming a composer. Her father discouraged her ambition, sending her to take voice lessons instead, explaining, “Women may not be good creators of music, but they’re good at interpreting music.” Ono eventually rebelled against such strictures to chart her own course. In 1956, she dropped out of Sarah Lawrence College and married composer Toshi Ichiyanagi. The two moved to a loft on Chambers Street, in Manhattan’s Lower West Side, and quickly fell in with the city’s experimental arts community. The loft became a site for “happenings” – mixed media events that featured spoken word, music, and experimental performance.

Ono performed at these and other events, often playing with ways to create sound; a 1961 concert she staged at Carnegie Recital Hall (adjacent to the larger Carnegie Hall) featured a piece in which dancers moved objects around the stage while wired with contact mics. She also experimented with how to use her own voice. “In 1962, I went into shouting, but not the kind of shouting that you know of me doing it over rock music,” she told me in an interview. “It was very similar to [her 1981 solo single] ‘Walking on Thin Ice.’”

In 1966, she went to London to participate in a symposium entitled “Destruction of Art,” with her second husband, Tony Cox. She met Lennon when he came to one of her solo exhibitions. Two years later, when they became a couple, they began making experimental recordings together. Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins, Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions, and Wedding Album mixed organic and electronic sounds, vocal manipulations, and improvisations; on “No Bed For Beatle John,” for example, Ono “sings” a newspaper article to an improvised melody.

Working with rock instrumentation necessitated a more aggressive vocal style. “I was from the avant-garde, so I was still a little bit structured at first,” Ono says. “But when I went to rock and we did all that stuff, the Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band kind of thing, I was loosened up by then from doing a few shouting pieces in London. And then I just felt great! The only thing was, because they were playing electric guitar and all that, to go over that and do your voice experiments was very difficult. So that was when all that came out like ‘Aaah!’ Those things started to happen because they forced me into it. Pushed me into it!”

Today, music aficionados could recognize Ono’s music as the bridge between the Velvet Underground and Patti Smith, with a vocal style later heard in the work by performers like the B-52’s or Diamanda Galas. But in 1970, devoid of that framing, listeners were perplexed, if not outright hostile. Klaus Voorman was startled when he first heard Ono singing, as he backed John and Yoko at a “Rock and Roll Revival” festival in Toronto in 1969. “She started screaming and doing this thing,” he recalls. “And people all stood there. And I looked at Eric [Clapton, also in the band], and we looked at our feet. We were really shocked, just as much as the audience.”

But by the time YO/POB was recorded, he’d gained an appreciation for her unorthodox style. “That record is incredible,” he says. “I love in particular ‘Why Not,’ where she sings really quiet, and John is playing on the guitar; she’s doing all the squeaky noises, and he’s doing the slide guitar and it’s really floating, really simple stuff. She turned him on to all this and he says that too, that he would’ve never thought of doing these things this way. It’s definitely Yoko’s influence.”

What’s especially exciting about the tracks in the new box set, is not only their length (about three times that of the original album), but also that the music is presented in its original raw state, before any editing or added effects. “Yoko did a hell of a lot of editing to it after the recording,” says Simon Hilton. “It is absolutely incredible. It’s making all of these decisions that you wouldn’t normally take, but she’s taken them with great bravery… they’re groundbreaking, in terms of not editing on the beat, but still editing somewhere that makes it work incredibly well.” Tracks were slowed down or sped up, enhanced with sound effects and delays, looping and sampling. “It was a very exciting record to do, because you never knew what was happening,” said the album’s engineer, John Leckie.

On “Why,” we can hear that the musicians were playing for nearly ten minutes before Ono chose to join them. “Why Not,” which runs over twenty minutes, has a bluesier cast to it. Shorn of its sound effects and manipulations, “Greenfield Morning” is more laid-back, but still just as haunting. Hearing just the bare tracks gives you a sense of being right there in the room with the musicians, caught up in the moment of creation. Voorman further explains their approach in the liner notes: “It’s not like really recording a song, it was recording a feeling. Ringo and my thing was, ‘We are the rhythm band, we’re just gonna put down the basis — some chair she can sit on and build a song around, build her music around.’” Three previously unreleased tracks flesh out the story; “Life” in particular percolates with a nervy energy, the musicians laying out a taut foundation for Ono’s ethereal cries to float upon.

It was the release of Rising in 1995 that helped lead to a reassessment of Ono’s earlier work. Old prejudices and misjudgments had faded away, and now younger musicians were eager to experience her music. L7 dropped a sample of Ono’s warbling into their track “Wargasm.” The Rising tour saw alternative rockers like the Melvins and Soundgarden joining Ono on stage. Remixes of her music by the likes of Cibo Matto and Tricky made her a regular presence at the top of Billboard’s dance chart. “When Yoko did her singing in Toronto [in 1969], the audience didn’t have any context to what she was doing,” says Voorman. “They didn’t know what it was supposed to be. So they were really shocked, I would say. Now, she has got an audience, and the people know what they come to see, and they know what she is presenting.” At present, the new mixes of YO/POB are only available on the Blu-rays in the “Ultimate Collection” box set, due to licensing issues; Hilton hopes to someday be able to release more material. But the original album, reissued twice since 1970, is readily available, and is well worth investigating as a barrier-breaking musical statement. For her part, Ono views her musical legacy with equanimity. “I feel that I always have my own voice and it’s different from others,” she says, “and if somebody wants to hear it, they will.”