It’s impossible to have grown up in the U.S. — or really anywhere in the developed world — and not heard Suzanne Ciani’s electronic music compositions and sound design. Most famously, she’s the creator of the “pop and pour” sound used in Coca-Cola commercials throughout the world. She’s also the composer of the intro music that plays before Columbia Pictures movies. Another fun fact you may be less familiar with: She became the first woman heard in a pinball machine when she leant her vocoder-recorded voice to the game Xenon in 1979, as well as composing its minimalist synth soundtrack.

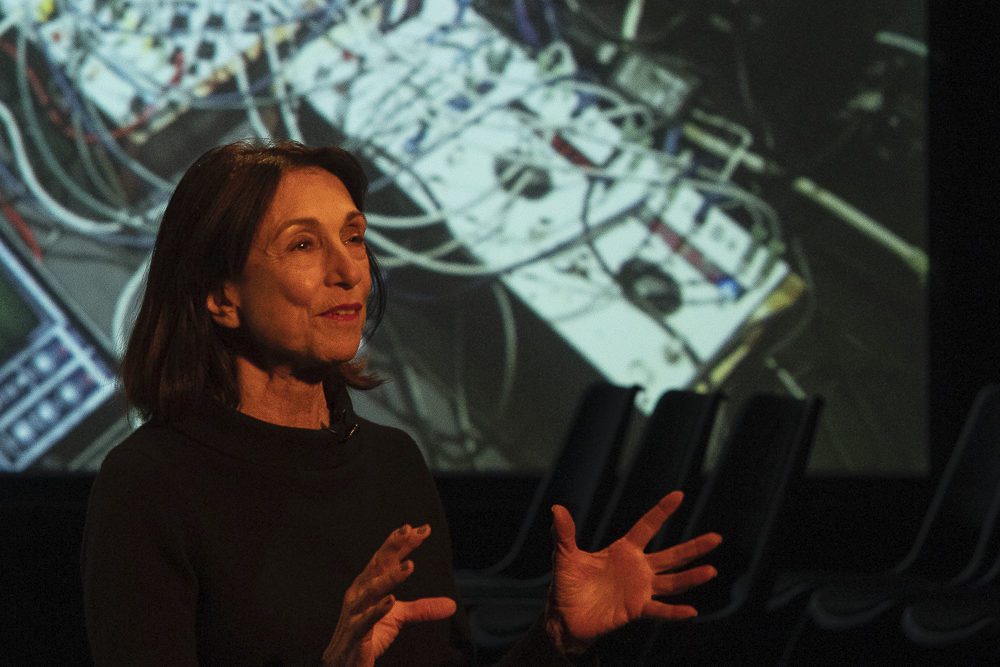

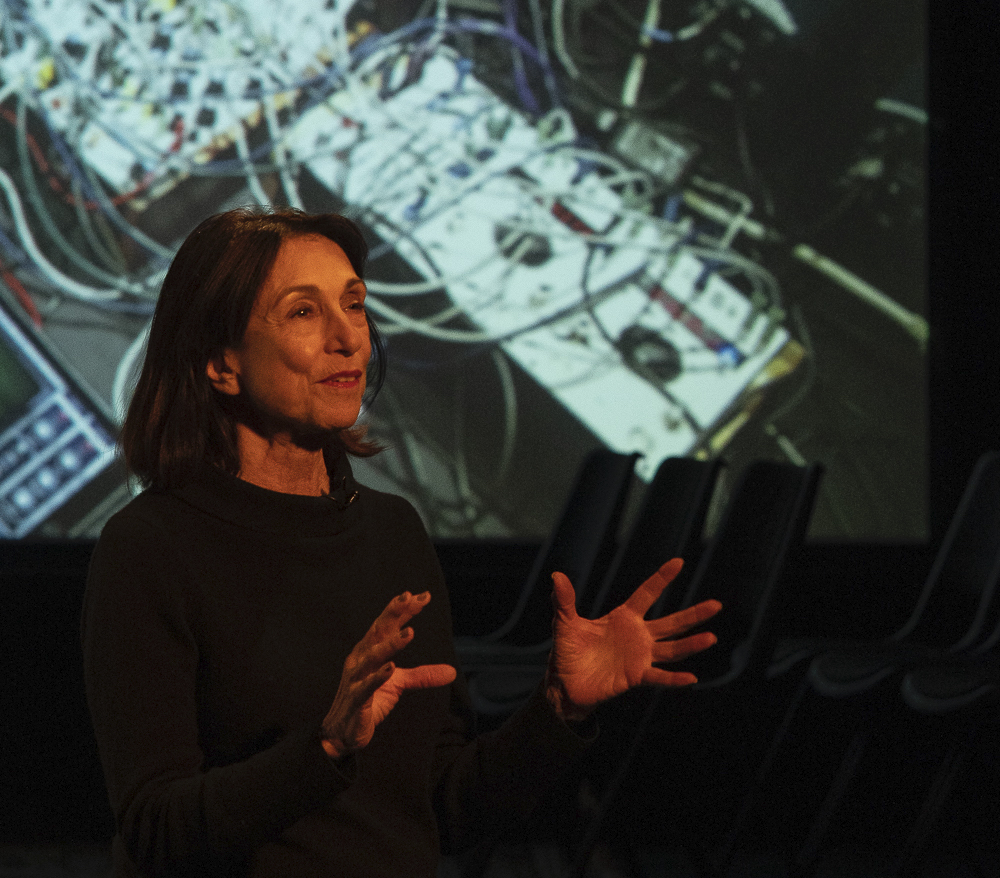

Ciani first became fascinated with electronic music while she was getting her master’s degree in composition at the University of California, Berkeley in the late 1960s. There, she met Don Buchla, creator of the Buchla synthesizer, and began renting out Buchla and Moog synthesizers at the tape music center at the nearby Mills College, where visitors could use the studio for just $5. “We need more of these facilities,” she says. “Kids are spending so much money now on gear. I understand that addiction to hardware.”

What she personally finds addictive about electronic music is that it’s “very variable,” she says, explaining that she’s constantly getting sent new instruments to try out. “It’s modular, so you put together your own customized instrument, and right now, there are thousands of modules to choose from, and it’s a bit overwhelming and a bit exciting,” she says. “When you play the piano, you wake up and the piano is there — it’s like, ‘oh, the piano.’ With electronic music, you wake up and there’s something new you have to investigate. You have to learn it. It’s always changing.”

“Always changing” appropriately describes Ciani’s career. Since 1970, she’s put out 15 studio albums and six live albums, some devoted to synthesizer and others with piano. The most recent, Improvisation on Four Sequences, is a recording of a live Buchla Quadraphonic performance in Geneva, Switzerland from January’s Festival Antigel. In it, you can hear the wide array of synthesizer sounds Ciani is known for, from the high-pitched and energetic to the slow and ominous-sounding.

“It’s a strange time to release because one is the pandemic, and two, it’s our social revolution, which is wonderful — it’s about time,” she says. “But I think that human connection is really what music is about, and we need that. We need it now. We’ve always needed it, but now I think it’s very comforting, and I think that in a way for me, I feel more comfortable now with something … that opens up a new language for us, and I think electronics does that.”

She also recently released “Music as Living Matter,” a hypnotizing and dynamic four-minute composition using a new type of analog synthesizer called the Moog Subharmonicon. Based on composer and music theorist Joseph Schillinger’s concepts, it features spoken quotes from the thinker, such as “music makes one believe that it’s alive because it moves and acts like living matter.” Visual artist Scott Kiernan created a video to visually represent the ideas the song expresses, with colorful vibrating geometric shapes.

“When we function as artists, we’re actually creating life — in a way, it’s an imitation of life,” Ciani explains. “Great art lives on. It has a life separate from the creator.”

The progression of electronic music as a genre has been as ever-changing over the span of Ciani’s lifetime as her career itself. Since the advent of electronic music in the ’60s, she’s seen movement away from physical instruments to computer compositions and then back to the analog synthesizer, which she views as advantageous because it provides real-time sound feedback as you play it.

“The kids said, ‘Hey, enough with all these digital menus and this computer interface — I want to touch it. I want to get feedback from the instrument itself,'” she says. “Kids want LPs; the kids want cassettes — what is all that about? Well, fundamentally, it’s about deconstructing the belief that technology marches forward and is always better, and that’s not true. It’s a sales pitch, and now we know we have a choice. There are so many different technologies, and some of them are better than others for certain things.”

During Ciani’s career — which presented many obstacles for her as a woman in an industry that was even more male-dominated when she began — she’s witnessed the women’s movement similarly come full-circle. “’68 was a huge women’s liberation moment – we peaked there, we got someplace, and then it fell,” she says. “And the next generation of women forgot. They didn’t even know they had been given certain rights that they assumed were always going to be there. And so then, the next generation came in, and those rights were being threatened again, and so they developed the energy systems — and every time we get to the crux of this wave, we get a little further along.”

The way she’s approached sexism in her own career has been through sheer stubbornness — refusing to listen to anyone who has tried to undermine her success. “I would just be like a little robot: If I hit that wall, I’d go someplace else,” she says. “If you have self-confidence, nobody’s going to get you down.”

In fact, for Ciani, playing the synthesizer is a form of self-liberation. “This is a liberating instrument,” she says. “It’s like Jackson Pollock on the canvas. You still have a canvas, but you’re not constrained.”

Follow Suzanne Ciani on Facebook for ongoing updates.