INTERVIEW: Madelin Lost Her Head on a ‘Mental Journey’ Interrogating Identity, Spirituality, and Art

Madelin pulses with sheer goddess vitality. Across her latest EP, a seven-song expedition of micro and macro concepts of the human form, particularly that of gender, sexuality and existential dread, called Then Her Head Fell Off, the Bushwick enchantress permits her voice to wriggle amidst waves of synths and midnight-rave glitter-dust. “I’m going to get my fix tonight / Cinch my waist up nice and tight / Maybe the answer’s in her eyes,” she coos, tantalizing nectar seeping from her pores.

“Monarch” is only the beginning; she soon sprouts vibrant, rainbow-textured wings and soars higher than she possibly could have imagined. “Broken Star,” paired with a just-released video that witnesses her juggling various existential thoughts, is soaked in her musical daring, as is other essentials as “In Fashion” and “Accidental Poetry.” Even “Dna,” which possesses one of the set’s most immediate hooks, still leans heavily on eccentric style while delving into the lyrical bite of today’s social issues.

“In a metaphorical way, this song’s about the chaos. You can’t control it. It deals with an early human and a modern human and them looking at the same landscape and it being completely different,” she says. “Where are we going? Our environment is in our hands, and we’re letting it slip through our fingers. We don’t seem to care. The whole song culminates in… are we going to keep repeating this cycle until we kill the earth?”

Severing formerly toxic cycles rises as the bedrock of much of Madelin’s work. I first stumbled upon her music exactly two years ago, right on the heels of the release of her self-titled EP, a brisk five songs that were certainly more stretched with mainstream latex. But they bore an undeniable personality all her own. “Good List” was the breakout hit, drawing in hundreds of thousands of Spotify streams (and its accompanying visual is a work of sexist-smashing glory). In prancing through the effervescence of mainstream appeal, Madelin has a knack for conjuring up quirks that really do set her apart.

Her magnetism lies in both her musical prowess and a fearlessness to challenge the establishment and burn it to the ground. The music is just the conduit to explore her role as a gender-busting queen in a world still suffocating from the male ego. Then Her Head Fell Off is further proof that her blood, sweat and tears are being put to good use. Her journey to this point, however, was a long, emotionally-exhausting one.

When I called her up recently, I admittedly knew very little of her backstory. All I really knew was that she once grew up on the glistening sand of Venice Beach, outside of Los Angeles, and she later moved to Brooklyn to pursue various artistic endeavors. I was also privy to the general outline of a former dead-end publishing deal and a management contract seeking to strip her of any and all identity.

Born into a very liberal household as Madeline Mondrala, music seemed to make the most creative sense for an inquisitive and fiercely independent young girl. She was often given free reign to explore, to sing (she began lessons at five), to write, to be free in her own skin. Her parents were “essentially atheists,” she says, but they “wanted to give me a ‘spiritual’ foundation. I’ll never forget that phrase. It’s weird to think about that now.”

So, they enrolled her in catholic school. Ironic, right?

“My parents never seemed to believe in any of that stuff. So, as far as spirituality goes, I had this kind of weird relationship with it,” she says. “My parents were atheists, and I was in a Catholic school where if you even questioned the existence of God, it was… ‘am I going to Hell?’ That was weird, but I always felt that I could explore my spiritually, and I was really encouraged to sing.”

Madelin’s first songs began to form and spring from her fingertips when she was eight or nine. Her synergy with the world had popped open, and there was no stopping her. In the coming years, she played, confronted, manipulated, sculpted and explored her burgeoning understanding of herself in art. Yet gender was something that still eluded her – which points to our greater transformation as a society. It hasn’t been until the last five or 10 years that the concepts of gender identity have expanded to include every color of the rainbow. “I think that’s why it has taken me so long to scratch the surface of that part of myself,” she says. “It was more that I just wasn’t aware that I could explore it. I think that caused a lot of confusion in my early 20s.”

Confidently unsure, Madelin packed her bags and headed for New York City in 2010. She began her studies in songwriting at SUNY Purchase to sharpen her craft. “You know, based on today’s standards of the music business, maybe it wasn’t the best, but it was good at the time,” she recalls, with a sly chuckle.

She soon began immersing herself in Brooklyn’s queer nightlife scene – which you can hear in vibrant neon hues on “Monarch” – and that’s the setting for her gender and sexual awakening. “I definitely identified so much with the queer scene in New York. I wanted to be in it and in queer spaces. Who wants to be in a straight bar, first of all?” she explains, laughing. “Even more than that, I felt like there were parts of me that I hadn’t really looked at. I wasn’t ever given the chance to question it for such a long time. I started to sense that maybe I hadn’t fully come to terms with it all or explored a part of myself, and I wasn’t sure what that meant.”

More uncertainties followed. “I wasn’t just like, ‘I’m definitely bi. Or, ‘I’m definitely whatever.’ Yes, it has to do with who you’re attracted to, but it also does have to do with your identity as a person and gender,” she says. “I’m just a very mentally-driven person. I’m more about the mental than the physical. My attraction to people is more of a mental experience. I think discovering that and how I feel about myself and my gender is not the most physically-expressed thing. It’s a mental journey I’m going on.”

While her personal expedition of gender, sexuality and overall identity was producing rich new layers, her professional life would be put through the wringer. She firmly planted her roots in 2013, and right out of college, was offered a shiny publishing deal with BMG. As it would turn out, things eventually soured. “It was the classic story of wanting to make somebody something other than who they are. I think they choose young people because they aren’t as self-aware and they don’t know themselves as well as an older person might. So, they’re easier to influence. That was happening, and I felt it happening. I felt really gross about it.”

Meanwhile, her manager pulled the plug on contact. “The day I released my [self-titled] EP, my manager stopped contacting me completely,” she says. “I didn’t hear from him for three weeks. And that was that.”

The damage done runs even deeper. Many of the songs she’d written, including “Accidental Poetry” and “Open Sign,” “didn’t make the cut in the eyes of my manager,” she says. But they lived to see another day on Then Her Head Fell Off; not only has Madelin’s voice has been given a chance to ripen and mature, but the songs have taken on new meaning, making a powerful statement about women, and creators, owning their art.

Does Madelin’s story sound a little familiar? It should. Pop titan Taylor Swift recently made headlines when she made a Tumblr post revealing details of a deal made between Scooter Braun and Scott Borchetta. In summation, Braun purchased Big Machine Records, which includes Swift’s entire catalog (six albums through Reputation). “For years I asked, pleaded for a chance to own my work. Instead I was given an opportunity to sign back up to Big Machine Records and ‘earn’ one album back at a time, one for every new one I turned in,” she wrote. “I walked away because I knew once I signed that contract, Scott Borchetta would sell the label, thereby selling me and my future. I had to make the excruciating choice to leave behind my past.”

A diehard Swift, Madelin has some thoughts on all this, as it relates to her own story, “I’m grossed out by it. You think of her as being so powerful. The fact that she doesn’t seem to be able to overpower these two gross guys, it makes me feel sad. I don’t like that they have that type of power over somebody’s work. The whole way it went about is horrifying.”

It was certainly something when she was going through it, but Madelin now believes it was necessary, vital even, for her present. “In a lot of ways, I truly think that my relationship with my manager and publisher falling apart is a blessing in disguise. No matter if you’re a ‘successful’ musician and have tons of followers, you could still be completely fucked over by the music industry,” she says. “It doesn’t matter who you are. People are in contracts for six albums that they signed, of course, when they were super young, because that’s when these people sign artists. You’re just in a holding pattern until you find some way to get out or you’re just stuck.”

Then Her Head Fell Off (wjich Madelin co-produced with Matt Speno and Eric Gerhardt) juggles big, shimmering pop choruses (“Monarch, “Dna”) and weirdly-addicting absurdity (“In Fashion,” “Open Sign”). Later, she offers up a lush interpretation of “Birthday,” a Sugarcubes original written by Björk. The flighty, distorted little tune bookends the project, almost as a signal of where she’s been and what’s to come.

“I love Björk. She’s my MOM,” she laughs. “I got into her whole catalog of work in college. I just loved all of it so much. I wanted to pay homage to her, but I didn’t want to do a Björk cover – that was too on-the-nose, so I felt that this was kind of cute.” She configures her performance around a remixed version by Justin Robertson, but when the lyrics burst, the production morphs into a whole new creature. Here, Madelin is at her finest.

Together, Speno (Madelin’s partner-in-life) and Gerhardt form the EMD/house duo Betamax, and there are essences of grungy dive-bars and oceans of bodies thrashing from too much booze and neon lasers woven into the EP’s fabric. Where Speno draws more explicitly from his love of synths, electronic drums and sampling of odd sounds, Gerhardt digs into his folk music sensibility, allowing particular sequences to ebb and flow untethered.

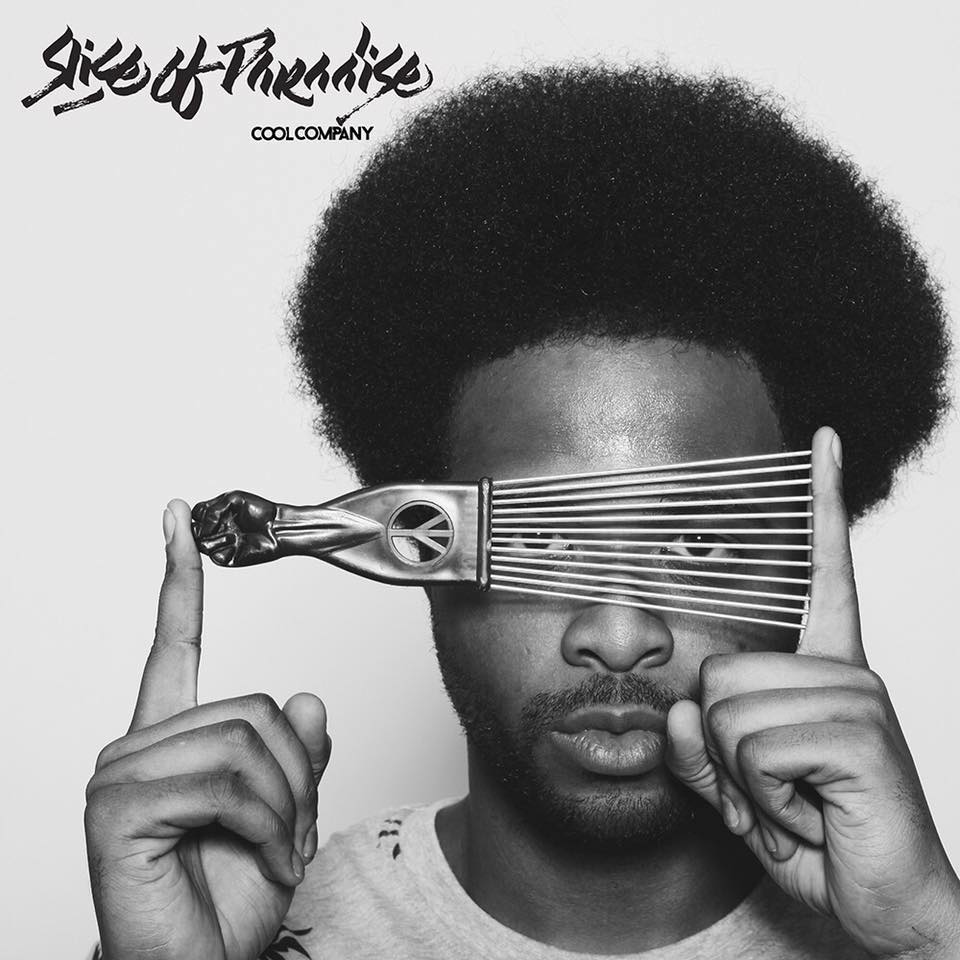

There’s a palpable liberation on display, underscored by the cover art, as well. The image, of Madelin posing triumphant on a self-made throne, recalls the Empress Tarot card and presents a culmination of her evolution. Years prior, she stumbled into a side-street Tarot shop and has been studying ever since. “I might seem like I’m really one of those out-there people. I just like the idea of a deck of cards that you can consult with. It’s the easiest way for me to explore the potential of there being some sort of spiritual realm that I can communicate with,” she says.

“If there’s any way that I’m going to do that, it’s going to be through Tarot. I love it. I do it casually, and I collect decks. I wanted to reference them in the photos for this whole era just because that was a part of what helped me discover more of myself – of asking questions about myself and answering them myself. You look at a card, and it has a meaning that you can interpret. But you’re also just interpreting it as you. It’s an interesting way to communicate with yourself.”

Those questions and answers guided Madelin down the less-traveled path, and a whole new batch of themes began to emerge. “A lot of the time it’s about me expecting or wanting to be at the end of the journey or to be in some satisfying place or to know that I’m going to get to this satisfying place. But the common theme is that there’s no destination. There’s always more work to be done,” she says. “There’s always more to learn, and there’s always more to know and discover. So, I think another common theme is to find some kind of flow within all that change all the time and to not be afraid of the work – but also not to bury yourself in it. It’s all about the balance of everything. That’s what I always get in some way from any reading. It’s about not getting stuck in one way of thinking, one of mode of working.”

The complexities of Madelin’s work only grows when our conversation shifts to her fascination with life’s duality. “Well, I’ve always been a little preoccupied with existential thoughts, especially as a kid. My night terrors were about that – the idea of dying. I was overwhelmed by the endless possibilities of what could happen once you die. I was scared of how many options there were and not knowing which one it was going to be. Cross reference that with: what if there is a Heaven? What if I’m just in Heaven forever and can’t escape it? All types of things of that nature freaked me out so much.”

With age, of course, comes wisdom to accept those things we can not change. “I have really embraced that uncertainty. I don’t feel afraid of death anymore. Obviously, I don’t wanna die, yet, but I feel almost intrigued by the idea of death now that I have an inkling into what might be happening here on earth,” the triple Gemini offers. “I don’t think our brains are able to comprehend really what’s going on, but I think it has something to do with duality. There are so many examples of duality on this earth, whether that idea of duality is just what is and that’s the point of everything – that there’s this or there’s that. Or if we’re some sort of school of souls to learn about duality. Maybe that’s what we’re doing. Or maybe we’re in a simulation… Who knows!”

“The common theme we can all agree on is duality here,” she beams. “Cleary, for some reason, we’re working through that idea. I feel like we can’t ignore that. The point is to realize that it’s the yin-yang. There’s a little good in the bad; there’s a little bad in the good. It’s all part of the same thing.”

In all, Madelin’s latest heart-torn manifesto is among the year’s boldest and most adventurous releases. With her work free and flying high, the singer-songwriter has more than enough time to process what it all means for her going forward. “I think I just want to focus on being happy. I don’t want to die with my eyes on the prize. I don’t want to be so focused on achieving something that I forget to enjoy what I’m doing and the life I have.”

“I want to find the balance between continuing to pursue music and to make music and to release music and also let myself explore other things. I’m writing a musical, so I want to focus on that. I want to slow down a little bit and smell the roses,” she says.