HIGH NOTES: How LSD Changed Music as We Know It

In 1965, at 2 Strathearn Place in London, John and Cynthia Lennon, George Harrison, and Pattie Boyd sat at their dentist John Riley’s dinner table sipping coffee. A few minutes prior, Riley’s girlfriend Cindy Bury had placed sugar cubes laced with LSD in their cups.

Back then, the drug was just beginning to leave labs and doctors’ offices. Riley didn’t even know what it was. “It was just, ‘It’s all the thing,’ with the middle-class London swingers,” John Lennon told Rolling Stone. “He was saying, ‘I advise you not to leave,’ and we thought he was trying to keep us for an orgy in his house and we didn’t want to know.”

Despite Riley’s request, the group headed out to the Pickwick Club. “We’d just sat down and ordered our drinks when suddenly I feel the most incredible feeling come over me,” George Harrison recalled. “One thing led to another, then suddenly it felt as if a bomb had made a direct hit on the nightclub and the roof had been blown off: ‘What’s going on here?’ I pulled my senses together and I realised that the club had actually closed.”

After that, they headed to another club called Ad Lib, where they screamed after mistaking the elevator light for a fire. “We were cackling in the street, and then people were shouting, ‘Let’s break a window.’ We were just insane. We were just out of our heads,” Lennon remembered.

That night would change music history forever. Arguably, it’s why “Tomorrow Never Knows” sounds so different from “A Hard Day’s Night” — and why many songs started sounding different in the 60s, Chris Rice, founder of the Psychedelic Society of New England and author of On Culture: Small minds, big business, and the psychedelic solution, tells me.

Acid “expands one’s mind to things that they could not imagine being possible before its use,” Rice explains. “Sonically, this results in increased experimentation of sound. This lead to things like lead guitar recorded backwards by numerous artists, The Grateful Dead recording air in different locations (dry air, humid air, etc.) because they thought it would add depth and texture to their music, and The Beach Boys recruiting The Beatles’ Paul McCartney to chew celery in the track ‘Vegetables’ to add percussive sound to that track. Clearly, these examples are a far cry from the simple ‘guitar bass drums vocals’ setup that was comfortable and familiar in earlier rock and roll.”

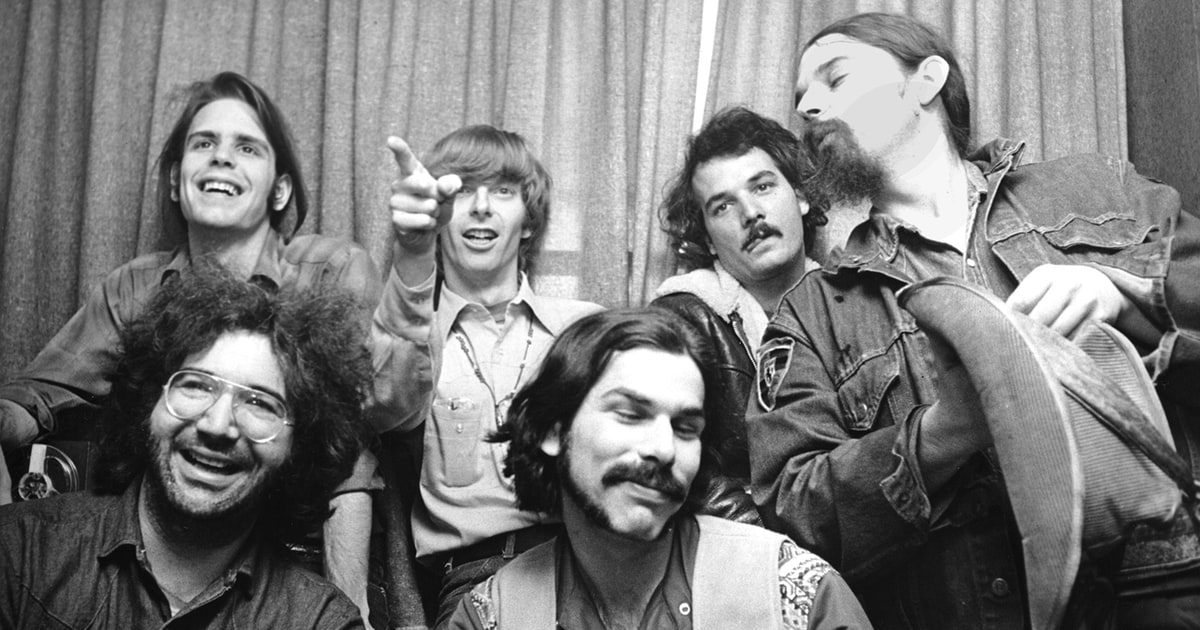

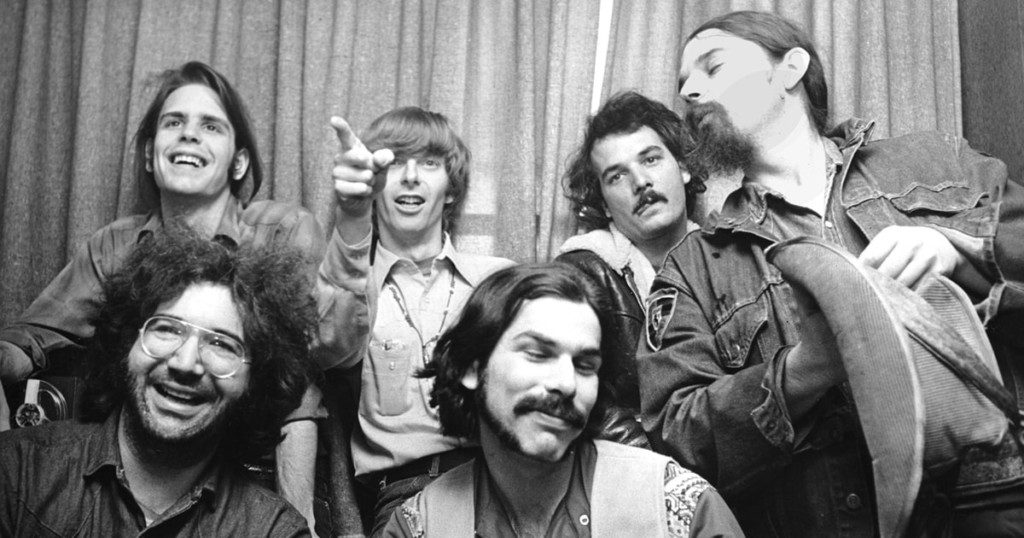

While The Beatles were tripping in London, The Grateful Dead was performing in Northern California’s “Acid Tests,” festivals that combined dance, art, and (of course) drugs, Philip Auslander, a Professor at the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Institute of Technology, tells me. Their sound engineer was chemist Augustus Owsley Stanley III, also known as Bear, who manufactured LSD and sold it to John Lennon, Pete Townsend, and other musicians. The Grateful Dead’s music was partially funded by the sale of this “Monterey Purple” and “White Lightning” acid.

The Dead and likeminded bands and artists like The Beach Boys, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, and Pink Floyd became known for their improvisational approach and “trippy” sound, which Sheila Whiteley defines in The Space Between the Notes as including “manipulation of timbres (blurred, bright, overlapping), upward movement (and its comparison with psychedelic flight), harmonies (lurching, oscillating), rhythms (regular, irregular), relationships (foreground, background), and collages.”

The distortion and Wah-Wah effects used by these bands mimicked the way acid distorts sound, Ido Hartogsohn, a Visiting Postdoctoral Fellow with Harvard’s Program on Science, Technology & Society, tells me. Layered studio arrangements like those in The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper and The Beach Boy’s Pet Sounds similarly brought out the sound’s details and arrangements the way LSD might.

Against the backdrop of these cutting-edge instrumentals and production techniques, a new style of lyric writing emerged. Phrases ceased rhyming, and images ceased making sense. The Beatles’ “I Am the Walrus,” for example, is rife with LSD imagery, from “sitting on a cornflake” to the “elementary penguin singing Hare Krishna.”

Even the band names became nonsensical, Richard Goldstein, who was a rock critic for The Village Voice in the 60s and used to drop acid with The Beach Boys, points out. Instead of carrying clear, simple meanings like The Penguins, The Crickets, The Animals, or even The Beatles, names like Jefferson Airplane, The Peanut Butter Conspiracy, and 13th Floor Elevator appeared to be selected purely for their aesthetic properties.

“It’s a very aesthetic drug,” Goldstein explains. Rather than perceiving sounds and images through the lens of a culturally prescribed meaning, people on acid interface more directly with sensory stimuli. This can lead to more universal, culture-transcending experiences with music. “We’re all connected through the subconscious, so when we listen to music on acid, it makes us have more of a tribal feeling,” says Goldstein. “It’s less intellectual more emotional and visceral.”

This shift from the intellectual to the visceral, from order to chaos, from logic to aesthetics, left an indelible mark on music, spawning other genres like pop psych, acid punk, and psychedelic trance and influencing folk, soul, and jazz, says Auslander. You can even hear their influence in modern rock bands like Tame Impala and Of Montreal, Hartogsohn points out. But psychedelic rock’s impact reaches beyond music to culture at large and even politics. It was a contributor, for example, to the counterculture and antiwar movements.

“LSD alters a user’s perception of what is important in life. As a result, the act of war seems entirely ludicrous,” says Rice. “Much of the elements of our culture constructed by our predecessors seem curious if not downright silly when viewed from the outside, as acid is prone to make people do. As a result, people’s worldviews shifted dramatically in the direction of peace and of love and of harmony, which seems, under the influence, to be the true meaning of incarnation in this realm.”

That’s the sentiment behind songs like “Love Is All You Need” and “Give Peace a Chance,” which John Lennon wrote after he became a regular (sometime daily) acid user. “[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”][We now] assume by default that popular music artists are socially aware and politically committed, a pure legacy of the psychedelic era,” says Auslander.

So, not only can we credit much of the past 50 years of music history to acid; we can also credit it for the spirit of the era this music helped usher in. The effects of LSD are environment-specific, Goldstein explains, but what it pretty reliably does is open people’s minds. Whatever happens to be around us as our minds open up may then get incorporated into our music and our worldview (which could also explain why there are so many stories about people who think they’re orange juice on LSD). And during the hippie era, which was already taking root by the time LSD entered the mainstream, people were tripping amid a call for peace and movement toward globalization.

Though LSD’s history is still palpable in today’s music, Goldstein laments that it isn’t more present. People today are “more interested in the solo cup than they were in the tab,” leaving music devoid of spirituality, he says. Kansas’s “Dust in the Wind” embodies the values Goldstein is nostalgic for with the line, “don’t hang on, nothing lasts forever but the earth and sky.” He looks back fondly on the “naïveté” that brought people to festivals with karma meters and mood rings. Acid “makes it easier to have that kind of reasoning,” he recalls. “Or lack of reasoning. But life is more than reason.” [/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]