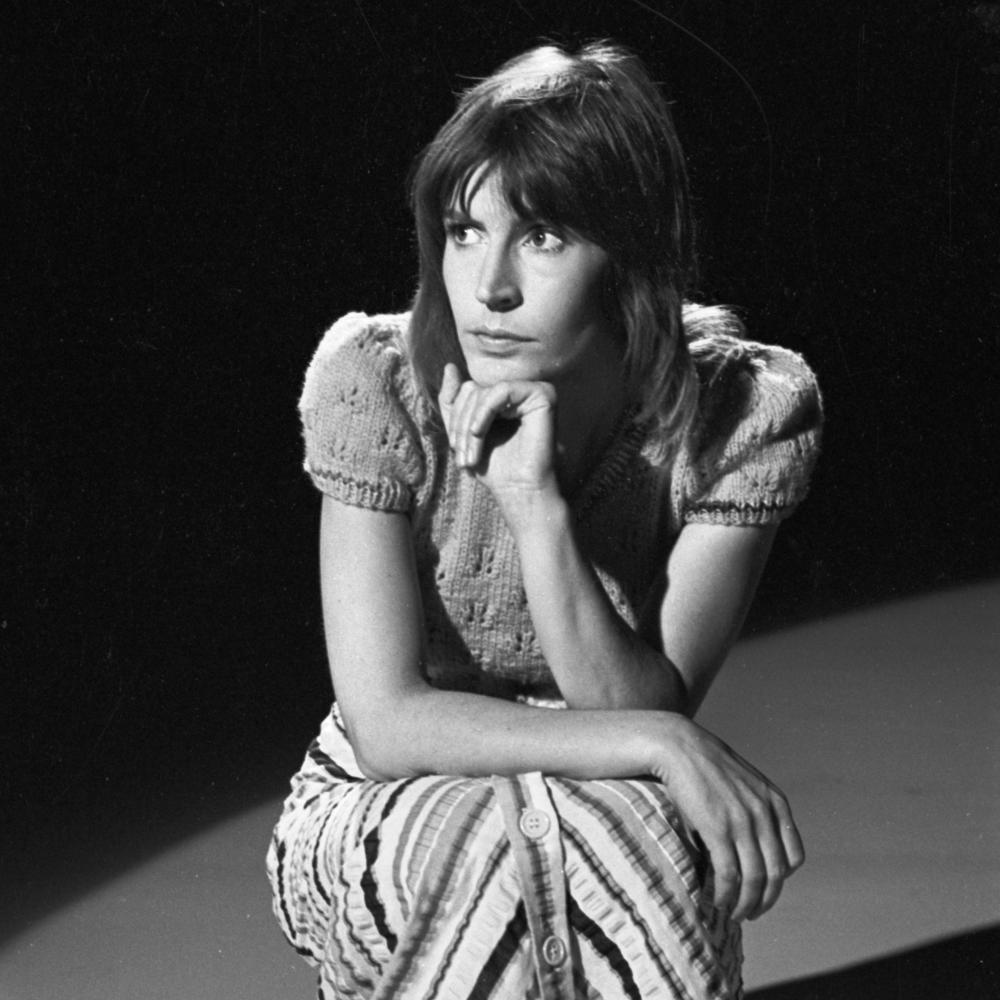

Remembering the Empowering Legacy of Helen Reddy

When Helen Reddy passed away on September 29 of this year, at the age of 78, she left a powerful legacy of music and activism—one that’s been with me most of my life.

In reflecting on her impact, I was transported back to June 1973: I was 6 years old and gripped by the opening line of “Delta Dawn” sailing from the car radio as my mom and I ran errands. “She’s 41, but her daddy still calls her baby.” Who was she? I was pretty sure that being “baby” to one’s father at that age was not okay. What was the story here?

“Delta Dawn” does tell a story, of a young Southern beauty wooed by “a man of low degree.” He proposes and then, in today’s parlance, ghosts. Crushed, she loses her grip on reality—roaming the streets year after year with her suitcase, waiting to begin their future together.

“Delta Dawn” was the first of Reddy’s songs I latched onto, despite the huge success she’d had the previous year with her most famous single, “I Am Woman” (the collective richness and struggles of womanhood weren’t something I could yet understand, so my love for that anthem would come later). As it turned out, “Delta Dawn” resonated with many; Reddy’s version, which went to #1 pop charts, had been a country hit the year before for singer Tanya Tucker, who recorded it at just 13 years old.

I’ve paid attention to song lyrics all my life, and Reddy’s yearning Dawn stayed with me—as did Ruby Red Dress, from Reddy’s 1973 hit “Leave Me Alone,” who meets an even worse fate than Dawn’s sham proposal: “Some folks say some farm boy/up from Tennessee/taught it all to Ruby/then just let her be.” I can’t find confirmation of it, but the song does seem to be about sexual assault; traumatized Ruby is left repeatedly mumbling “Leave me alone,” plunged into a mental crisis from which she doesn’t know how to recover. It does not sound like whatever happened to her was consensual; and even as a kid, I heard that, though I couldn’t tell exactly what happened. At 6, I don’t think I knew what rape was, but I could understand that the guy had done something very wrong to this woman and that it had damaged her. It’s kind of shocking that the song was such a hit on pop radio.

But that was one of Reddy’s special powers. She made not one but two ’70s smashes from stories of women manipulated and betrayed by men; somehow, with her pleasing voice and keen pop sensibilities, she was able to make them sell.

Granted, not everyone was convinced. Frank Zappa made fun of her appeal in his “Honey, Don’t You Want a Man Like Me?”: “She was an office girl/Her name was Betty/Her favorite group was Helen Reddy.” But numbers don’t joke. In 1973 and 1974, Reddy was the world’s top-selling female vocalist. She sold approximately 25 million albums during her career.

Helen Maxine Reddy was born in 1941 in Melbourne, Australia, to vaudeville performers Stella and Maxwell. She too began performing, at age 4—but then married a friend of her parents, Kenneth Claude Weate, at 20. “It was instilled in me: You will be a star,” she told People magazine in 1975. “I got very rebellious and decided this was not for me. I was going to be a housewife and mother.” The marriage produced Reddy’s daughter, Traci, but lasted only a few months.

In 1966, Reddy won a local talent contest that offered passage to New York City and, for the final winner, the chance to record. She and Traci, then 3, travelled to the States. Though she didn’t get the prize, Reddy decided to stay and try to launch her career.

In 1968, she met talent agent Jeff Wald—and married him three days later, the timing in part so that she could remain in the country and work. Wald became her manager, and together they attempted to promote her music. After years of struggle (and, Reddy later recalled, the need to spend chunks of their scant savings on roach spray), she released a single in 1971; the A-side made no impact, but the B-side was a cover of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” from Jesus Christ Superstar, which went to 13 on the charts (it’s been reported that Reddy didn’t like the song much, finding its heavily subservient lyrics irritating). Wald and Reddy kept pushing; “I Am Woman” broke the following year.

After “Leave Me Alone,” Reddy hit with Alan O’Day’s eerie, mysterious “Angie Baby” at the end of 1974. Here again was a ballad I could get into. Angie is a young woman who has been pulled from school for being “a little touched”—i.e., another Reddy heroine dealing with some kind of mental illness. She’s a music addict and loner, hanging out in her room with her radio and her daydreams.

She’s also another Reddy character called “baby” at a non-baby age. However, Angie is no Dawn. When a neighborhood boy comes by while her parents are away, all too ready to exploit her, let’s just say it doesn’t work out for him. If you take the lyrics literally (and just shy of my 8th birthday at the song’s release, I did), he enters Angie’s room; is trapped somehow by the power of her radio; and is physically drawn into it when Angie lowers the volume. As far as the town knows, he has vanished. What Angie knows is something else: “The headlines read that a boy disappeared, and everyone thinks he died/’cept a crazy girl with a secret lover who keeps her satisfied/It’s so nice to be insane! No one asks you to explain/Radio by your side—Angie baby.”

My real-life friend Angela (also called Angie) and I thought this song was the coolest thing: magic Angie turning the tables on her would-be abuser, then keeping him around for her amusement. The world agreed on its appeal; the song was a hit even in countries where other Reddy singles had not been. Talk about girl power.

With that, let’s return to “I Am Woman.” Dawn, Ruby, and Angie gripped me immediately, while I didn’t register the message in “I Am Woman” fully when I was 5. But for many years since, the song has often brought emotional tears to my eyes. It doesn’t matter to me that Reddy’s sound was not radical, that it lacks any edge or hip irony—this song sounds heartfelt and earnest, and why shouldn’t it? I don’t care that Alice Cooper called Reddy “the Queen of Housewife Rock”—and neither did she: That “means I’ve reached a lot of people in a simplistic manner who would never go to a lecture or read an article on women’s lib,” she responded in the 1975 People profile. I think “simplistic” is uncharitable; I’d go with “plainspoken,” conveying a clear point in a strong way.

I’d love to say that having “I Am Woman” in my consciousness from a young age steered me clear of major mistakes, and of the “wisdom born of pain” that it attributes to women. But this isn’t true. Nor was it true for Reddy, whose 1982 divorce from Wald resulted in part from Wald’s years of cocaine abuse, and involved a prolonged custody battle over their son, Jordan. But the song lends me solace when I stumble, strength to persist, and added sweetness in times of success.

Though Reddy usually covered the songs of others, she wrote the lyrics for “I Am Woman” herself, with the music by her friend Ray Burton. Interviewed for Australian TV in the ’70s, she described looking for a song like it and finding only stereotypes of strength: “I am woman, w-o-m-a-n, I can cook a mess of grits faster than you can,” she joked. “I realized that I was going to have to write the song. I was sitting in bed one night, and the lines, ‘I am strong, I am invincible, I am woman’ just kept going over and over in my head, and I realized that was the beginning of something.”

The Equal Rights Amendment was passed the year the song came out; Roe v. Wade was decided shortly after it hit #1. Helen sang it for the Dawns, the Rubys, and the Angies; the housewives and divorcees, factory workers and megastars. She sang for women everywhere, and she always will. Her children summed up her impact in a statement upon her passing: “We take comfort in the knowledge that her voice will live on forever.”