After my parents separated, my mom converted our home into what she liked to call “The House of Freedom.” Upon entering The House of Freedom, it was recommended you remove your bra. There, the Halloween decorations hung around into the New Year and Christmas lights punctuated our window frames long past their respective season. In The House of Freedom we took dinner on the couch, our plates sat on pillows propped on knees while a movie played. One of mom’s favorite exercises in “freedom” was the constant attempt to dissuade my studious pursuits. “And if the homework/brings you down/then we’ll throw it on the fire/and take the car DOWNTOWN!” she would sing.

At eight, this infuriated me. First of all, we didn’t have a downtown. The prospect of homework was wildly more exciting than puttering down the single street that made up my town’s “epicenter.” Secondly, I knew how these things worked. Neglecting your homework, like smoking cigarettes, was gateway behavior. If I didn’t respect my scholastic duties, then I wouldn’t pass the upcoming test, which meant I wouldn’t make it to high school, wouldn’t go to college, and would most likely die poor and alone.

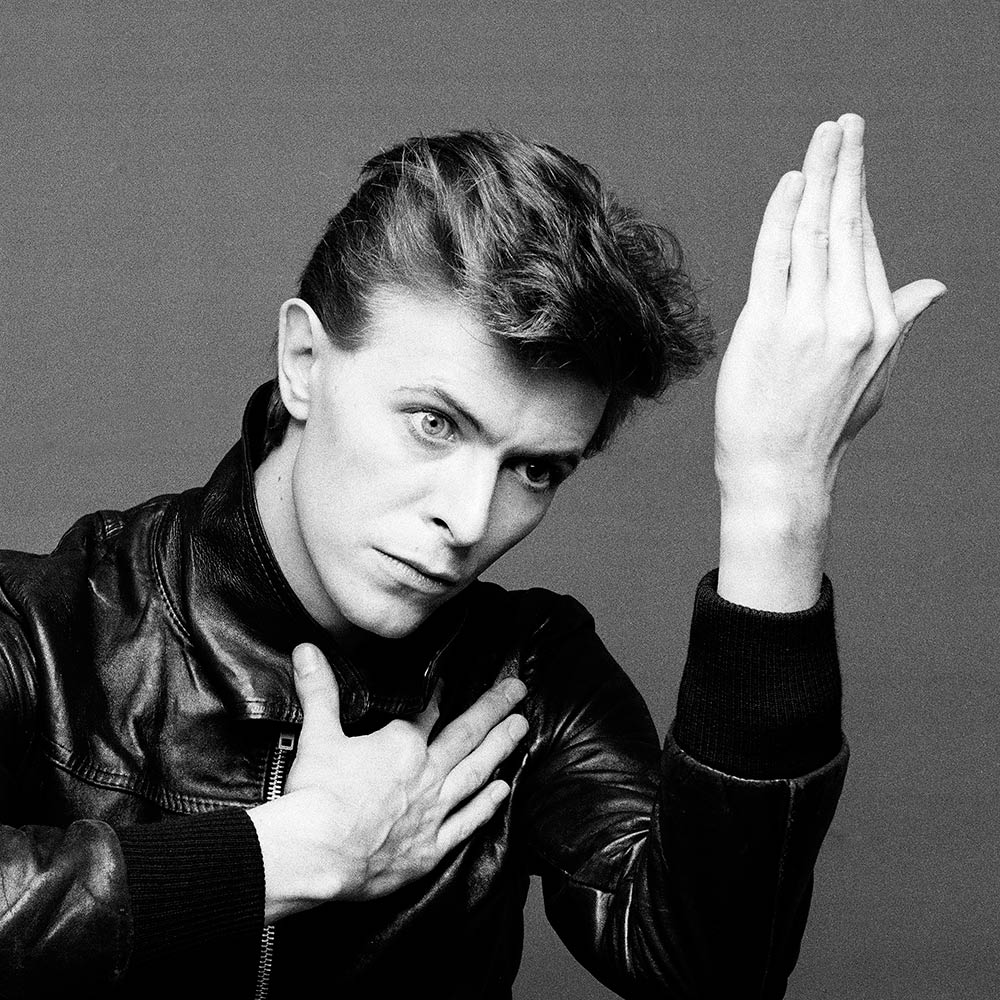

What I did not know, was that this bizarre line my mother belted at me was not in fact her own material, but David Bowie’s, specifically lifted from the song “Kooks” off of 1971’s Hunky Dory. As with many aspects of culture that tremendously impact one’s life, Bowie floated into my frame of awareness long before I recognized his importance. His 1983 smash record Let’s Dance played at all of my parents’ trademark parties. I ogled at his Goblin King in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth before I could spell. And though I have no evidence to prove it, I suspect his music scored a large portion of my gestation period. But my first conscious acknowledgment of his art had to be with Hunky Dory…with that line from “Kooks.”

In the shadow of his death in January, I cannot go long without conjuring the exact moment I heard of his passing. Oddly enough I had pitched an article to The Guardian hours before his death. The subject? What could Bowie’s Blackstar teach us about longevity in the music industry? Yikes. I woke the next morning to a tweet from The Guardian reading: “Remembering David Bowie.” I felt sick, and in my sleepy delirium thought for a moment that I may have killed him with my pitch. I desperately wanted to call my mother, who would later jest that I had in fact killed Bowie. But it was six in the morning in New York, and she lives by Pacific Standard Time, forever “three hours younger,” as she says.

As a music journalist I think a lot about the associative powers music has. I can’t say it is true for everyone, but for me, music has an intravenous drip into memory. The first time I heard a specific record, where I was, and most importantly, who played it for me, can all be summoned with the first chord of a song. This of course can occasionally be more of a curse than blessing, but not in the case f Bowie.

As I listened to tribute show after tribute show in the days following his death, there was a remark I heard from nearly every DJ: that one of the reasons Bowie’s passing is so mournful, is that we associate his music with the loved ones who shared it with us in the first place. So all the while I am grieving David Bowie, I am thinking of my mother as well, who, I should say for the sake of levity, is very much alive. But I can’t help but wince at the memento mori at play here-if I’m this choked up about someone I’ve never met, the thought of things to come in later life terrify me.

Within the span of a few years “Kooks” was our song. My mom still couldn’t lure me from my school books, but my newfound enthusiasm for punk rock lead me to her record collection. It seemed that every band I listened to all worshipped the same ivory idol: Bowie. He was omnipresent in the art world, cross-cultural even. One minute aiding the careers of proto-punks such as Iggy Pop and the next singing Christmas carols on network television with Bing Crosby. And in the year leading up to his Thin White Duke period, he became the first Caucasian artist to appear on Soul Train in 1975. Think about that.

Everything I loved pointed to him. When faced with the task to “put something on” while dinner was in the making, I would shuffle over to our massive China hutch and crack open the bottom cabinet. Only a handful of my mother’s records remained-maybe 60 or so, all peeling spines and smudged vinyl. Where the rest had gone was and still is a point of contention between her and my dad.

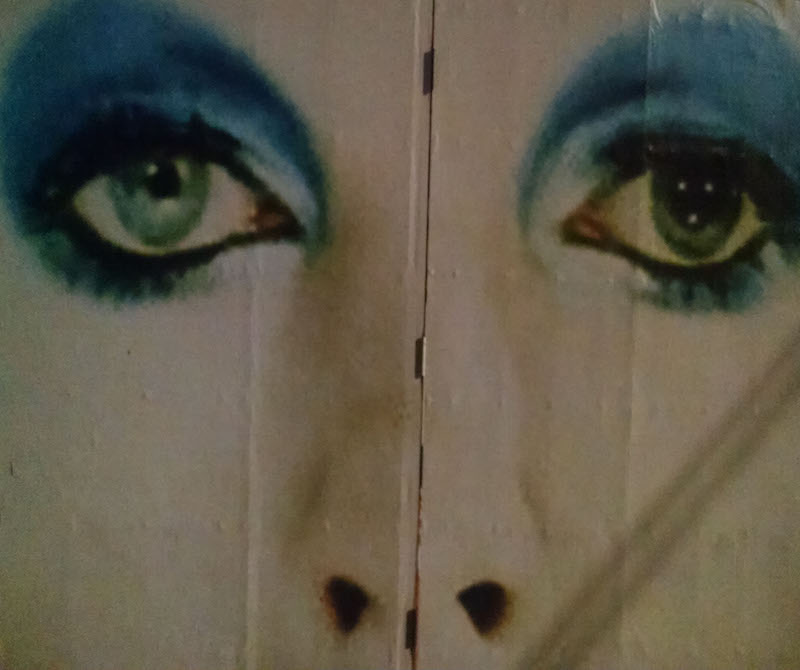

For our family, records weren’t just records, but tangible emblems of what is lost and gained in divorce. Who originally owned what was constantly debated, and my mom, having already endured two previous marriages, had brilliantly tattooed her record sleeves with a little blue star. Her copy of Aladdin Sane wore its star smack in the middle of Bowie’s forehead.

That China hutch was my doorway to The Stones, The Specials, The Pretenders, Wire, Big Country, The English Beat, and Blondie. But the big one was of course Bowie, who influenced most of those bands. She didn’t have everything, but quite a chunk: Hunky Dory, Pin Ups, Diamond Dogs, Young Americans, Lodger, Aladdin Sane, The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars.

I’m not sure which album I leapt to right after Hunky Dory, but Diamond Dogs couldn’t have come long behind. I was reading Orwell in school and was thrilled to hear the slinky, red-mulleted man put his dystopian themes to pop songs. The opening poem “Future Legend” mesmerized me…I didn’t know you could kick off a record like that. And when the last stanza stumbled into the title track, mom and I would bark in unison: “AS THEY PULLED YOU OUT OF THE OXYGEN TANK/YOU ASKED FOR THE LATEST PART-AY!!!”

I always thought that line was utter brilliance-a self-reflective jab and the self-destructive hedonism of the 1970s perhaps. To mom, I think it hit a bit closer to home. Maybe a smiling reprimand of those she lost to too much fun in the same decade. Maybe it was a salute to her own desires, ones she kept at bay for the sake of us kids.

She always had a specific way of interacting with her Bowie albums, a personal touch for each song. When we listened to Ziggy Stardust she’d come alive during “Suffragette City.” She loved to change the lyrics around, which enraged me as self-righteous 12 year old, but now I ascribe it to her exasperating charm. Instead of “Suffragette City,” it became “Surfer Cat City,” an autobiographical nod to her hometown of Huntington Beach.

Mom was expecting my call on January 10th. “It’s weird, but I think you’re more upset about this than I am,” she said. We laughed at that because we are good at laughing when things go wrong. I told her I’d cried, but omitted the fact that I was more visibly shaken than I was at Grandpa’s funeral. It is not something I am proud of, or able to explain. The thing is, I can’t entirely justify the melancholy that I felt, and still feel. Or rather, I can justify the misery itself, but not its magnitude when compared with the thousand other tragedies of daily life.

The day after Bowie passed I listened to BBC 6 Music. In between songs and DJs lamenting there were occasional newsbreaks discussing not only his death, but also your everyday tales of murder, war, poverty and starvation. The latter camp should clearly elicit more woe; and yet, shamed as I am to say it, the former is what brought me to tears. As with my composure at my Grandfather’s funeral, I am not proud to admit this, but I also have no control over it.

Could it simply be that from birth we are pursued by one sickening headline after another? And therefore become impervious to their scratch? Surely, that must have an effect. But I also suspect that the rarity of beauty plays a supporting role here. Perhaps Bowie’s vast, profound and exceptional art has so penetrated our cells, his absence aches like a phantom limb.

In all my years of listening to Bowie, I’ve never spent too much time analyzing his personal life or lyrics. All of it seemed perfect to me, and I feared that any attempt at decoding would strip the artist of his mysticism (as if Ihad the power to do that). But now that he is no longer with us I’ve allowed myself to pour over interviews for the first time, and I must say that he is more mystic to me than ever. Strangely because of how wonderfully human he could be…how down to earth, kind, and hilarious. Every newfound facet of him becomes a little present, like a longtime friend or lover who still manages to surprise you. I now find so much joy in knowing that “Kooks” was in fact written for the birth of David’s first child Duncan Jones; it is, at the end of the day, a celebration of parenthood, of unconditional love. Apparently my mother has known this all along.